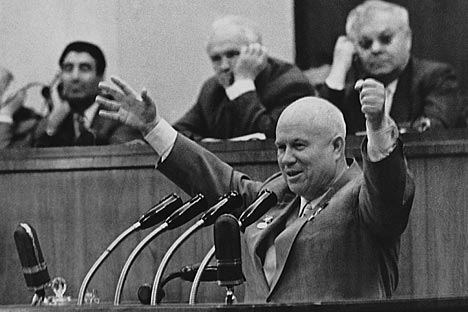

Khrushchev had a characteristic speaking style, and he was not afraid to be colorful. Source: Itar-Tass

Nikita Khrushchev, the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, is a symbolic figure with an entire era of Soviet history, the thaw, associated with him.

The thaw period included the disclosure of Stalin’s cult of personality, Gagarin’s space flight, “Khrushchyovkas” (Khrushchev-era apartments), a flourishing of literature and cinema, dissidence, the Cuban missile crisis and more. He was as contradictory as his era.

Khrushchyovka: a two- and five-story, massive apartment building from Khrushchev’s time

Kolkhoz (“kollektivnoe khozyaistvo”): a farming collective

Khrushchev’s biography is utterly mundane for a Soviet bureaucrat.

He was born in the Kursk countryside. At age 30, during Stalin’s repressions, he was the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party.

No hint of liberalism was evident; on the contrary, he ruthlessly disposed of so-called enemies of the people. Overall, he agreed with Stalin while Stalin was still alive.

It is even said that at Kremlin drinking fests, Stalin forced Khrushchev to dance the gopak, a Ukrainian dance, in an embroidered Ukrainian shirt. And this is entirely plausible.

However, when Stalin died, Khrushchev quickly took the reins. The rehabilitation of political prisoners started. Passports were issued to collective farmers, who under Stalin did not have the freedom to move around.

But generally speaking, Khrushchev thought more about the future than the present. He coined a slogan: “Catch up with and overtake America!”

He promised that the current generation would live under communism, and that communism would arrive in 1980. Hence people later joked that instead of communism, the Olympics occurred in 1980.

Khrushchev was a striking figure and striking leader. Under Brezhnev, he was stigmatized for voluntarism. Yet such a person was needed in order to take the country out of dormancy.

He was always bursting with ideas. He started the Virgin Lands campaign. He disparaged abstract artists at a famous exhibition at the Manezh. (Regarding one painting, he said, “A donkey waves better with its tail!”) He issued an order to plant the whole country with corn.

Things got to the point of absurdity: people tried to cultivate corn even in Karelia, in the north, where in theory it cannot grow. He threatened to attack England and France.

Anything could happen with him. On one side, political prisoners were being freed, while on the other, tanks suppressed the Hungarian uprising. On one side, the dissident Solzhenitsyn was being published, while on the other, shots were fired into a peaceful demonstration in Novocherkassk.

He had a characteristic speaking style, and he was not afraid to be colorful. He could easily say to American diplomats, “We will bury you!” “We have only one dispute with you — on the land issue: who buries whom,” Khrushchev said. He announced to Nixon, “We shall show you Kuzka’s mother [We’ll make your life hell]! For a long time the Americans puzzled over what “Kuzka’s mother” meant.

He banged his shoe on the UN platform during debate on the Hungarian crisis. This was remembered. Not a single president could permit himself that.

He was a lively person, emotional, passionate and completely lacking in complexes. He called Mao Tse-tung an old boot. He said to the U.S. representative to the UN, “People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.”

Talking to New York mayor Robert Wagner, he said, “I almost just slipped and called you Robert Petrovich. When I was younger, I worked in a factory where the manager was an engineer named Robert Petrovich Wagner.” This sounded warm and human.

Unlike Stalin, Khrushchev was not at all a monumental person. He was simple, even down home. He was spry, rotund, and bald. He had a snub nose and protruding ears — so he looked like any peasant or clerk in a wine shop.

Moreover, he constantly gesticulated. At cocktail parties he waved his glass around so much that the cognac in it would dance around.

Much in Khrushchev was childlike. During after-lunch strolls in the park, he would clutch to his chest a small radio receiver that had been given to him in America.

It is said that during that time the village melodies he loved were broadcast especially for him. The radio amazed him to the depths of his soul. He was also amazed by war games — new bombs, planes and so on.

He was mocked and called Ivan the Fool on the throne. But he was loved. Indeed, he was captivating.

His grave is in the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow. On the grave stands a monument by the renowned sculptor Ernst Neizvestny — whom, incidentally, Khrushchev assailed and poured his last words on.

But at the end of his life he wrote a will in which he asked that Neizvestny create the monument. This monument shows a head inside a black and white frame. It is impossible to portray Khrushchev in a single color. He was a complex man.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox