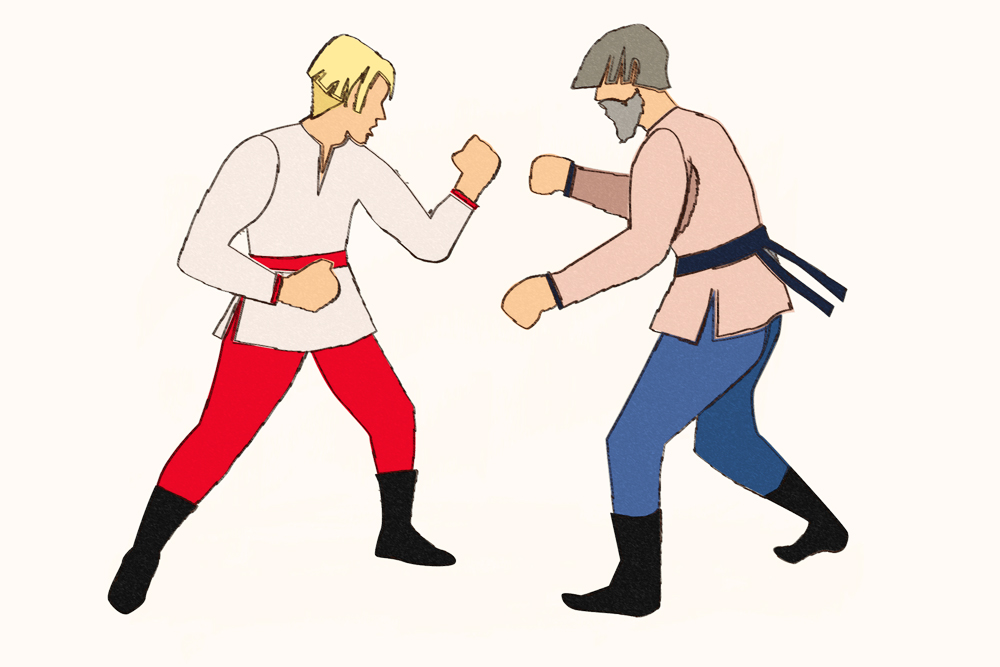

Hand-to-hand, or “one-on-one” fights were similar to modern-day boxing matches. Combatants had to remain on their feet at all times, and fighting on the ground was forbidden.

Alena RepkinaTime and time again the Russian authorities have outlawed fist fights, yet many of the Russian tsars were known to have enjoyed watching them. Likewise, it once wasn’t uncommon for members of the nobility to face off against the common folk. Such fights were generally concluded with all-round heavy drinking.

Russians began using their fists to resolve differences long ago. The first reference to fist-fighting is found in one of the earliest pieces of ancient Russian literature, the Primary Chronicle, dated to the year 1048.

The author of the Primary Chronicle, Nestor, doesn’t paint these fights in flattering terms. Nestor was a monk, and the Orthodox Church considered fist-fights to be a paganistic pastime that went against divine will.

Two centuries later, Metropolitan Kirill went beyond simple condemnation and introduced harsh punishments against the practice, declaring that participants of bare-knuckle boxing matches would be excommunicated and that those killed whilst playing the brutal sport would be refused a church burial. This last measure essentially equated fighters with those who had committed suicide.

This didn’t stop the fist-fighters, however. Organised brawls took place all around ancient Russia on a regular basis, generally at the same time as large festivals and in open places. The week of Maslenitsa, a time of carnival celebrations before the Lenten fast, would see people fight with particular zeal. The clashes attracted crowds of spectators, merchants did a roaring trade in mead and beer, and fireworks were sometimes put on for the occasion.

Source: Alena Repkina

Source: Alena Repkina

Both single combat and mass fights were practised. Hand-to-hand, or “one-on-one” fights were similar to modern-day boxing matches. Combatants had to remain on their feet at all times, and fighting on the ground was forbidden. The first to fall down or to admit defeat was declared the loser. In most instances, he would remain alive.

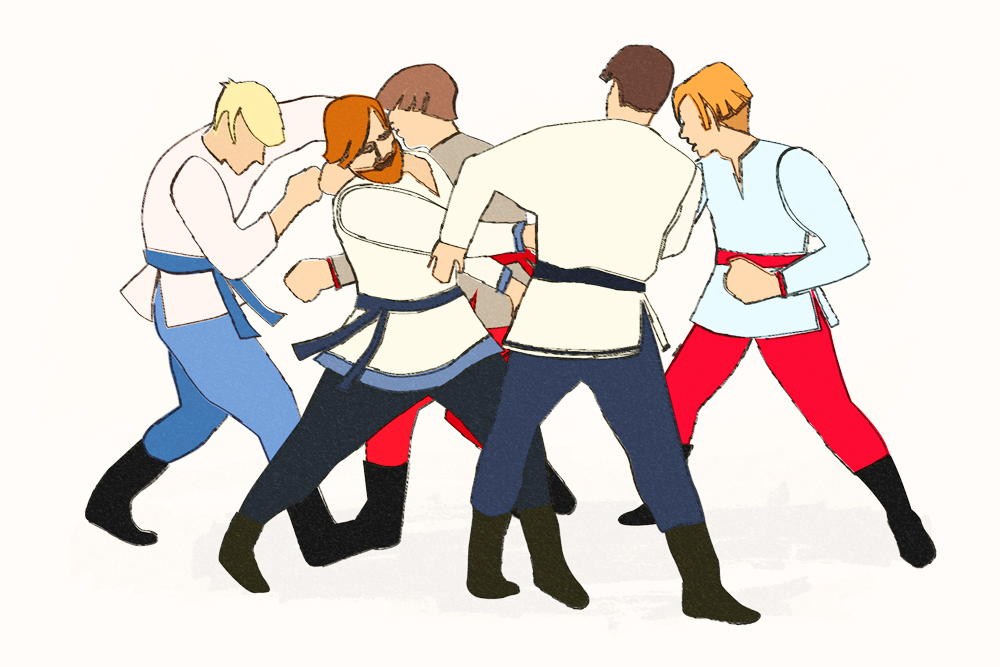

Large-scale contests also took place. Residents of neighboring streets or villages, inhabitants of opposite sides of a river or even members of different professions were set against one another. There were two main types of these fights: so-called “chain” fights, and “wall-on-wall” fights.

The first variety was reminiscent of modern “tag team” wrestling matches: Everyone would eventually fight everyone else, and once a combatant had defeated one opponent he would face off against the next. “Wall-to-wall” fights, meanwhile, involved two opposing groups lining up in rows to face one another, allowing tired participants to drop back and regroup whilst the fight continued.

Mass fights were, of course, the most spectacular. They were also the most dangerous, since in the heat of battle the rules of war became impossible to enforce. Fights ended lethally with frightening regularity, in spite of all the measures designed to prevent such an outcome.

These measures were numerous: it was forbidden to strike an opponent who had admitted defeat or who was lying or sitting down, as it was to hit an opponent who was bleeding uncontrollably. Only fists were to be used, although shoulder shoves were permitted, and fighters could use both hands at the same time. The targets of choice were generally the ribs, the head and the solar plexus.

Combatants were also instructed to wear thick hats and protective gloves to soften the force of the blows that they gave and received. Unfortunately, this rule generally caused more harm than good – fighters would hide rocks or strips of metal in their gloves.

Yet, however rough the fighting got, the opposing sides would always conclude proceedings by sharing a feast, as old tradition dictated.

Bare-knuckle fighting was generally considered a form of amusement, and its sporting dimension was not taken seriously. The sport of lapta (similar to baseball) was included in Peter the Great’s compulsory training program for Russian army conscripts; fist-fighting, on the other hand, never boasted such an honor, even if it might seem ideally designed for military training.

Fist-fights even served on many occasions as a means of resolving legal disputes. This somewhat unorthodox form of dueling allowed plaintiffs and defendants to settle their differences directly with one another. Or, indeed, they could hire more skilled belligerents to do the fighting for them.

In the 17th century, an ukaz (an official imperial proclamation) was issued that imposed the punishment of beating with sticks on those caught bare-knuckle boxing. Repeat offenders were even sentenced to exile. Yet despite the harshness of these laws, Russia’s rulers partly turned a blind eye to the fighters’ reckless pursuits. Peter the Great was a great fan of fist-fights: He saw in them a display of Russian fighting prowess. Even Catherine II’s favorite, Count Orlov, was a distinguished fist-fighter.

In 1917, bare-knuckle fist-fights were outlawed by the Bolsheviks. Since then, the fights have never reappeared in their original form. Ancient Slavic forms of combat are still practiced in traditional martial arts clubs, but these are fairly uncommon, and organized tournaments are held only very rarely.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox