Experimental Soviet taxi, 1964 (by artists and constructors Y. Dolmatovsky, A. Olshanetsky, A. Chernyaev).

Archives of Moscow Design MuseumThe first London Design Biennale, to be held Sept. 7–27 at Somerset House, will be devoted to industrial design and new technologies. Russia will be represented by an exhibition from the Moscow Design Museum called “Discovering Utopia: Lost Archives of Soviet Design." The theme of the biennale is 'utopia,' in honor of the 500th anniversary of the publication of Thomas More’s Utopia.

On the eve of the event, RBTH spoke to the head of the Moscow Design Museum, Alexandra Sankova.

RBTH: Why are you bringing Soviet design? Doesn’t contemporary Russian design have anything to offer?

Alexandra Sankova. Source: moscowdesignmuseum.ru Alexandra Sankova. Source: moscowdesignmuseum.ru |

Alexandra Sankova: There are commercial exhibitions, like a design week, where everyone wants to display contemporary works, things that have just been released or are about to appear on the market, or concepts. This biennale is an international event where each country seeks to show its achievements, its history. It is more about the image, about presenting some interesting discoveries.

For example, at this year’s Venice Biennale of Architecture, the Russian pavilion was devoted to VDNKh (Vystavka Dostizheniy Narodnogo Khozyaystva, or Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, is a permanent general purpose trade show and amusement park in Moscow – RBTH). Of course, we have interesting modern buildings, too, but the curators wanted to show how this unique Soviet-era exhibition center and park is being revived and what a fascinating history it has.

RBTH: Then why did you choose Soviet design and not some other historical period?

A.S.: Many people abroad think that Russia first had avant-garde art, and then a blank period, just copying of Western designs, and that right after the 1990s it was flooded by Western brands. We wanted to show that there was Soviet design, even a whole system of design.

Furthermore, the theme of the London biennale is 'utopia.' So we wanted to present the utopian side of Soviet design – just look at how many astonishing futuristic projects came out of the All-Union Research Institute of Technical Aesthetics (VNIITE). And those designs were never produced on a large scale because the country simply did not have enough industrial capacity to do it.

VNIITE building at VDNKh. Source: Archives of Moscow Design Museum

VNIITE building at VDNKh. Source: Archives of Moscow Design Museum

Among some of the initial ideas for the exhibition, we considered outlining the full history of utopian projects, from avant-garde to present day, but we would not want contemporary Russian products to be branded as ‘utopian.’

After all, we want contemporary design to develop and new items to be produced.

RBTH: Could you tell us more about the exhibits please? Are there any among them that were ahead of their time?

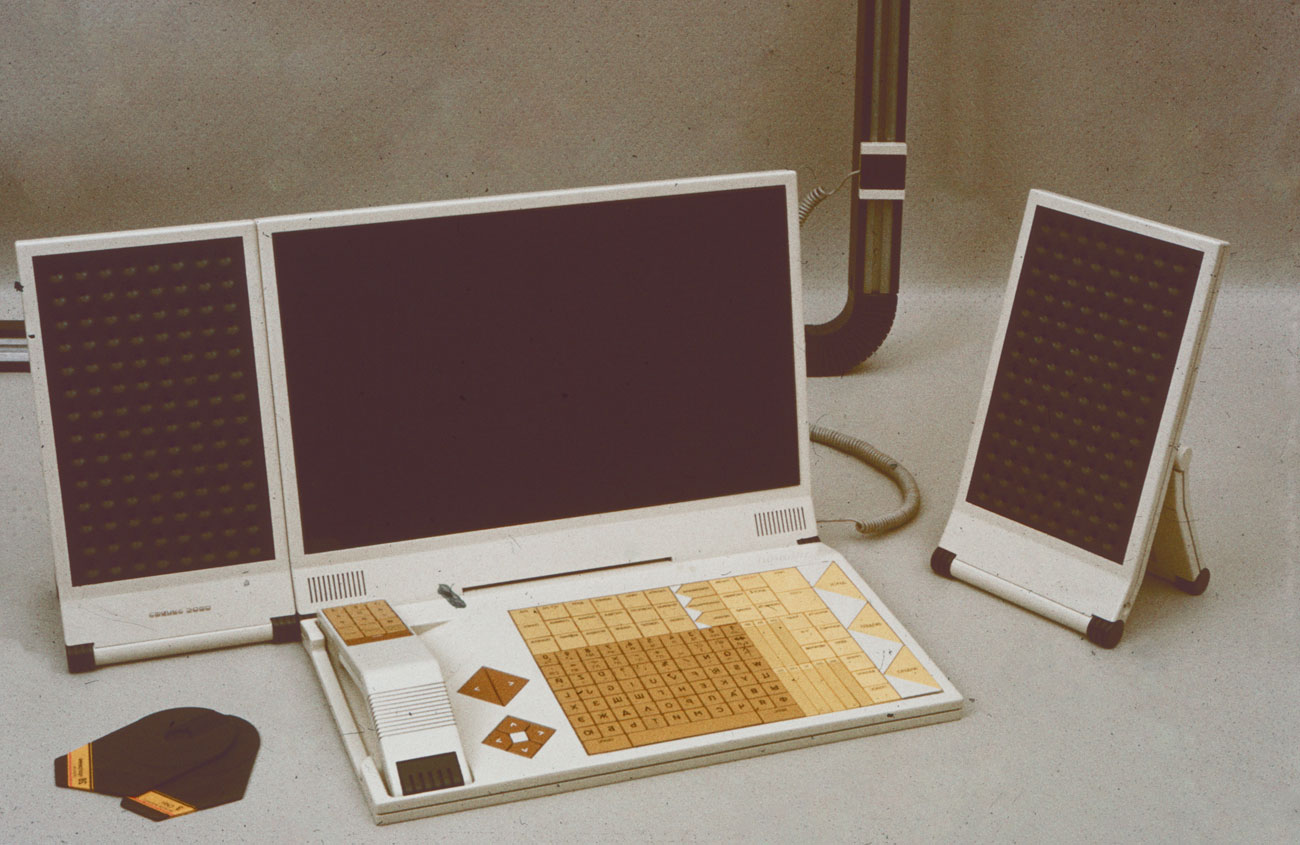

A.S.: The range of VNIITE designs that we are presenting has some very interesting pieces, like the concept of a future domestic electronic system called Sphinx. It was developed by VNIITE’s Future Planning Department.

The Sphinx station (1987, designed by D.Azrikan in collaboration with A.Kolotushkin and V. Goessen). Source: Archives of Moscow Design Museum

The Sphinx station (1987, designed by D.Azrikan in collaboration with A.Kolotushkin and V. Goessen). Source: Archives of Moscow Design Museum

It should be noted that the technical design for these projects was never specifically commissioned. For example, the State Committee for Science and Technology assigned the task to create a revolutionary computer. That is why the Sphinx station had futuristic square disk drives (for floppy disks), a remote control and small monitors that could be detached from the computer station. In other words, what we have today, a touch pad and mobile phones – it was all envisioned back then.

Generally speaking, VNIITE was unique in that it developed design programs for the entire Soviet Union. Some of them were implemented, like BAMZ (a design program called Household Appliances for Magnetic Recording), the production of tape recorders and players, everything to do with electronics. But there was also a program that was never implemented, which will also be presented in London. That was a program for sorting refuse and recycling, called Vtorma.

In other words, items and projects that existed in the West had equivalents developed in the Soviet Union. VNIITE designers not only fashioned a corporate image and decided where dumpsters should be located, but they also designed a very nice uniform for garbage collectors and garbage truck drivers. They considered the whole waste cycle, including where recycled materials could be used. In other words, it was not just design thinking, but process design. They even designed campaigns for motivating people to sort their garbage.

Additionally, they calculated the economic benefits for the state in all their projects.

RBTH: Does the exhibition feature any projects that could be implemented today?

A.S.: With some modifications and additions, I think all these projects could be put to use. VNIITE had a Theory and History Department as well as an Ergonomics Department [studying how work environments could be improved to optimize productivity]. All the design principles were thoroughly developed not only from the aesthetic and functional points of view, but also from the point of view of process optimization, of increasing productivity.

The theoretical work from those departments could inform the development of present-day projects. They devised many fundamental things that should at least form part of the training of future designers.

We are convinced that the time has come to remember the unique experience of VNIITE, its projects and designs that were ahead of their time. Soviet design has its own identity and its own history, which we would like to show to others. I believe that the VNIITE ‘school’ deserves to have a place in the history of world design.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox