The writings of foreign explorers writers offer an understanding of how life in Earth’s coldest country was possible before the age of modern heating systems.

Alexey Malgavko/RIA Novosti Portrait of Adam Olearius by Jürgen Ovens. Source: Public domain

Portrait of Adam Olearius by Jürgen Ovens. Source: Public domain

The German geographer, historian and mathematician Adam Olearius first arrived in Russia in 1633 as secretary to a diplomatic mission. He spoke Russian, and subsequently made several more trips to Russia. In his book Travels of the Ambassadors sent by Frederick, Duke of Holstein, to the Great Duke of Muscovy and the King of Persia, he described what it meant to travel by sleigh, the typical mode of transport of those times: "Some of us lined the floor of the sleigh with felt and we lay on it in our long sheepskin coats, which can be acquired very cheaply there, and on top we covered the sleigh with a felt or woolen rug: this kept us warm and we even sweated and slept as the peasants drove our sleigh onward."

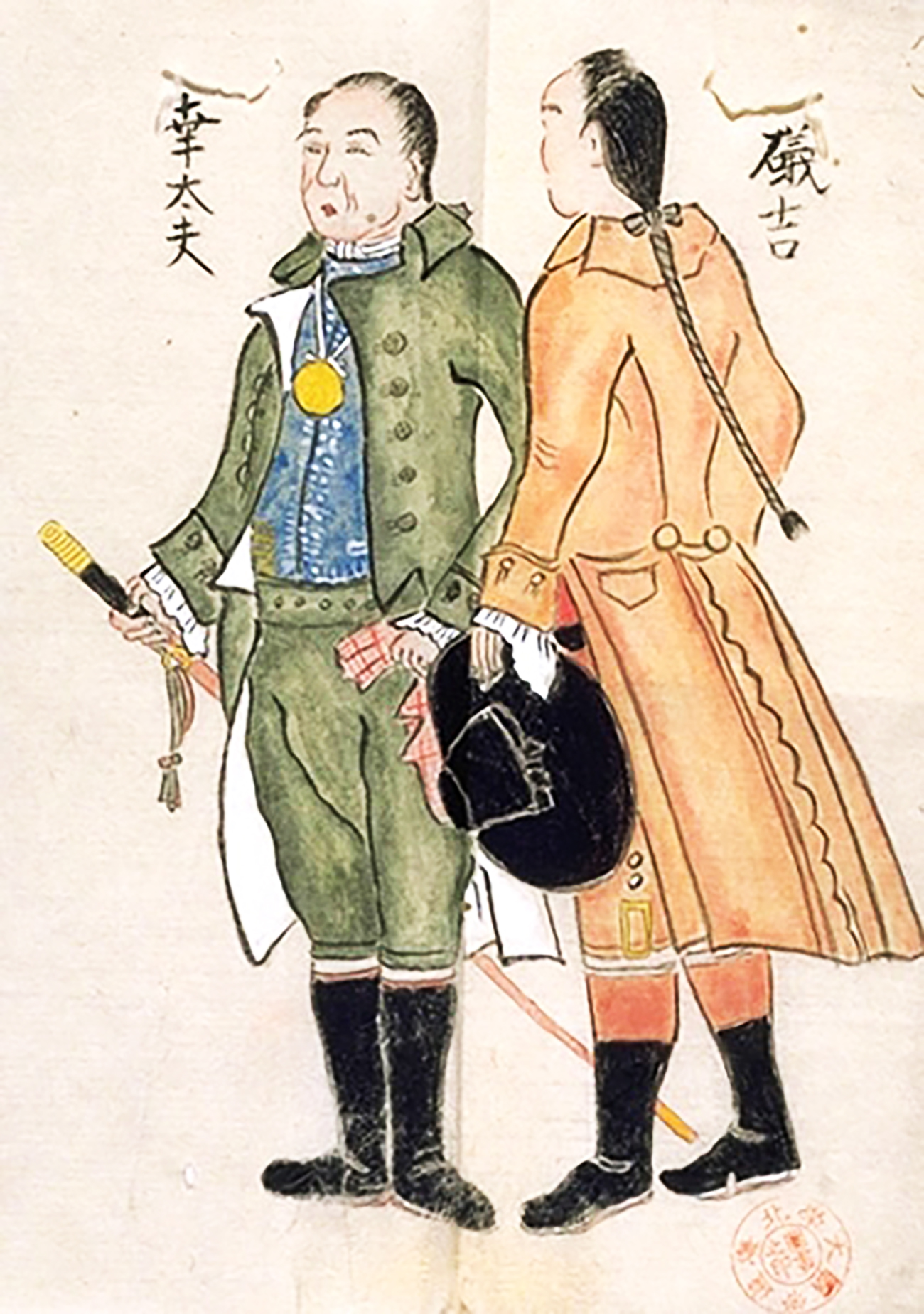

Kodayu and Isokichi, two Japanese casteways returned by Adam Laxman, 1792. Source: Public domain

Kodayu and Isokichi, two Japanese casteways returned by Adam Laxman, 1792. Source: Public domain

After he was shipwrecked off Russian shores in 1783, the Japanese ship's captain Daikokuya Kodayu spent ten years in Russia, met Catherine II and carried out cartographic studies. In his reminiscences, A Brief Account of a Northern Drift, he described, with a characteristic directness, the smallest details of everyday life in this unfamiliar civilization - for instance, the particularities of Russian lavatories at the end of the 18th century and how they were used in winter. He enthusiastically recalled how the Russian nobility lived: "The upper classes even install stoves in their privies to keep them warm."

Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Self-portrait in a Straw Hat. Source: National Gallery London

Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Self-portrait in a Straw Hat. Source: National Gallery London

Artist Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun, fled the French Revolution and settled in Russia, where she painted dozens of portraits of the Imperial family and St. Petersburg high society. She published her memoirs upon return home, and recalled that: "the Russians have perfected ways of heating their houses to such an extent that in St. Petersburg you can be completely unaware of the cold if you avoid leaving the house with the onset of winter. The stoves everywhere are so good there is actually no need for fireplaces; they are mere objects of luxury."

Furthermore, she was struck by the winter gardens which the grandees of Catherine's time built in their palaces: "For Russians it is not enough to have spring-like temperatures in their rooms in winter; many rooms are adjacent to glazed galleries filled with the best flowers, which we only get to see in May.

"We must go spend the winter in Russia to avoid the cold," was how the artist summed up her observations after returning to a snowy Paris.

Portrait of Louis-Philippe de Ségur (1753-1830). Source: Palace of Versailles

Portrait of Louis-Philippe de Ségur (1753-1830). Source: Palace of Versailles

Historian and diplomat Count Louis-Philippe de Ségur was French ambassador to the court of Catherine II. He accompanied her on her celebrated "Taurida Progress" - a more-than-six-month journey across Russia, unprecedented for its time, which the Empress carried out with a retinue of 3,000. He left valuable memoirs of that period describing the customs of the time.

This is how he described the winter leg of the journey: "Our carriages seemed to fly along on their high runners. To protect ourselves from the cold, we wrapped ourselves in bearskin furs, which we wore over finer and more valuable clothes also made of fur; our heads were covered with sable hats. As a result, we did not notice the cold even when it was 20 degrees below freezing. The coaching stations were so well heated that we were more likely to suffer from excessive heat than cold."

Astolphe de CustineI. Source: Public domain

Astolphe de CustineI. Source: Public domain

French writer and traveller Marquis Astolphe de Custine was famous as the author of the book, Russia in 1839, published in Paris in 1843, which became a bestseller. The book was even banned in Russia, so harsh and critical was his account of Russian realities and the lifestyle of the local upper classes.

Custine did not forget to mention the frosts which "granite is helpless to resist."

"The buildings standing in a semicircle opposite the imperial palace are nothing but a failed attempt to mimic an antique amphitheater; they need to be viewed from a distance; from close up you see only decorations which need to be plastered and painted each year to make the damage wreaked by the harsh winter less noticeable. The ancients built edifices using enduring materials under a benign sky; here, in a destructive climate, people build palaces with logs, houses from wooden boards and churches of plaster; this means that Russian workers do nothing but repair in the summer what was damaged in the winter; nothing can withstand the local weather - even seemingly very old buildings were rebuilt only yesterday; stone here is as durable as in other countries lime."

"People who live in a country where summer and winter temperatures vary by up to 60 degrees should abandon the architecture of southern countries," was the writer's advice. "But Russians have got used to treating nature herself as their handmaiden and not to care about the weather."

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox