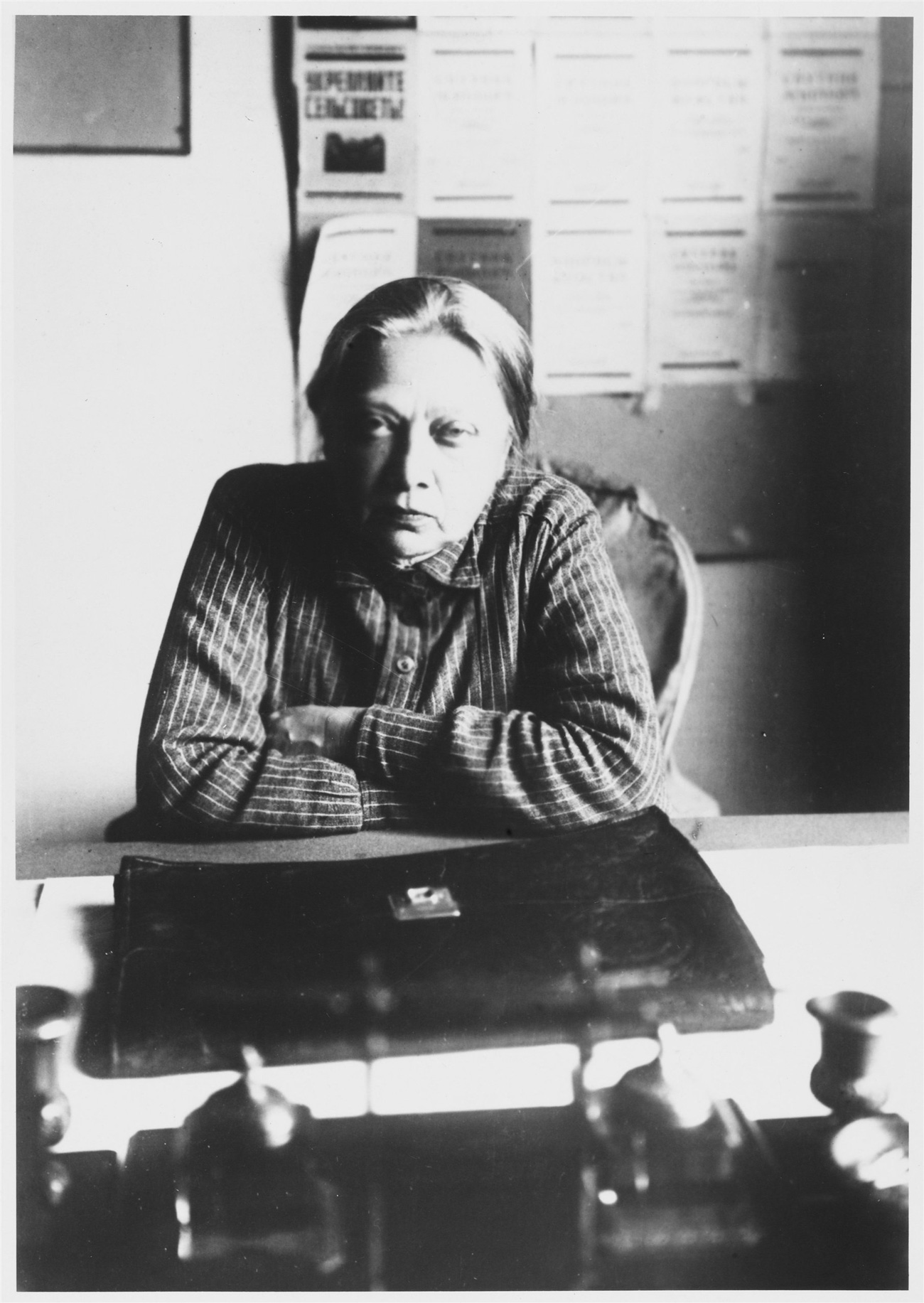

Nadezhda Krupskaya was married to the architect of the October Revolution, the first Soviet leader, Vladimir Lenin. Photo: Nadezhda Krupskaya among pioneers.

RIA NovostiThere's a popular joke among Russian university history tutors: a clever way to check a student’s knowledge is to ask, “What was the surname of Mrs. Krupskaya’s husband?” If a struggling student randomly replies, “Krupskiy,” then he'll certainly be kicked out.

Anyone with a sense of history knows that Nadezhda Krupskaya was married to the architect of the October Revolution, the first Soviet leader, Vladimir Lenin. Before his triumphal return to Russia in 1917, Lenin spent 16 years in underground revolutionary party work together with his loyal companion and committed Marxist, his wife.

Like many other revolutionary figures, Krupskaya was not from the working class, and was born into a privileged but financially struggling family. Source: RIA NovostiA

Like many other revolutionary figures, Krupskaya was not from the working class, and was born into a privileged but financially struggling family. Source: RIA NovostiA

Like many other revolutionary figures, Krupskaya was not from the working class, and was born into a privileged but financially struggling family. She graduated high school with a gold medal, and in her childhood the future militant atheist was very religious. Later, she wrote that, “I grew up in loneliness, without an ability to communicate my thoughts and wishes to other people. God was the only one to understand the vacillation of the human soul.”

At the age of 21, Krupskaya left the Church and sought to replace her religion with Marxism. In 1890, she first came into contact with Marxist ideas through a radical political discussion group in St. Petersburg. At that same time, she taught geography, history and math at an evening school for adults. This was the beginning of her interest in state public education and cultural policy that was very important to her when the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917.

Krupskaya first met Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (later known as Vladimir Lenin) in 1894 as a result of her revolutionary activity; in fact, while attending a discussion group. Already in 1897, when Lenin was arrested for sedition and exiled for three years to Shushenskoye (2,800 miles from Moscow), Krupskaya wrote that, “we've gotten to know each other rather well.” They had to arrange a church marriage so she could join him as his wife. “We had to put up with this comic situation,” Krupskaya remembered later.

While some historians saw the marriage as a union of two dedicated revolutionary enthusiasts, Krupskaya said it was not purely in order to destroy the monarchy. “We loved each other passionately. The fact that I don’t write about it doesn’t mean that there was no poetry and no youthful passion in our lives.”

Politically, the couple certainly kept very busy: translating books about foreign labor movements, building relationships with Western socialists, and pondering prospects for a revolution. At the end of their exile in 1900, Nadezhda and Vladimir absconded to Europe where they often changed residence: Munich, London, Genève, and Paris. All these years Krupskaya was her husband’s loyal companion. For instance, she helped in communication with other socialists by encrypting correspondence.

Krupskaya first met Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (later known as Vladimir Lenin) in 1894 as a result of her revolutionary activity; in fact, while attending a discussion group. Source: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

Krupskaya first met Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (later known as Vladimir Lenin) in 1894 as a result of her revolutionary activity; in fact, while attending a discussion group. Source: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

Krupskaya suffered from Graves' disease, an incurable illness at that time. This disease affects the thyroid gland in the neck, causing the eyes to bulge and the neck to tighten. It also causes female infertility, which may explain why Lenin and Krupskaya never had children. According to Krupskaya’s contemporaries, the illness caused her grief and suffering.

Krupskaya was also hurt by Lenin’s affair with the French-Russian communist revolutionary, Inessa Armand, which began in 1911 and continued to at least 1917. That romantic relationship was proven by Armand’s love letters to Lenin, but Krupskaya stoically accepted the situation and, moreover, became friends with Armand. Lenin nevertheless stayed with Krupskaya, choosing a strong friendship with his wife.

Krupskaya found consolation in social activity and believed that, “One has to know how to merge one's life with the life of society. This is not asceticism. On the contrary, the fact of this merging, the fact that the common cause of all working people becomes a personal matter, makes personal life richer.”

Krupskaya suffered from Graves' disease, an incurable illness at that time. This disease affects the thyroid gland in the neck, causing the eyes to bulge and the neck to tighten. Source: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

Krupskaya suffered from Graves' disease, an incurable illness at that time. This disease affects the thyroid gland in the neck, causing the eyes to bulge and the neck to tighten. Source: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

In 1917, Krupskaya returned to Russia with Lenin after the autocracy’s collapse, and supported all of her husband’s decisions. In 1920, she became chairwoman of the Soviet Union’s Education Committee (“Glavpolitprosvet”).

Lenin’s declining health was tough on Krupskaya, however. He suffered his first stroke, left unable to speak and paralyzed on his right side. His wife tried to help him recover, but it wasn’t for long. Lenin died in January 1924.

After Lenin’s death, Nadezhda found herself isolated and ignored despite the nation’s outward displays of respect for her as Lenin’s closest companion. Krupskaya criticized Stalinism, and was an opponent to Stalin and his inner circle. She complained in 1937 to one of the Bolsheviks about “the abnormal atmosphere, poisoning everything.”

Krupskaya died because of acute appendicitis in 1939, just a few days after her 70th birthday. Stalin, who always hated her, carried her ashes during the funeral ceremony. She was buried in the Kremlin Wall, a few meters from the Mausoleum where her husband rests for eternity. Lenin’s devoted friend, wife and colleague is still close and follows him, even in death.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox