Kids with a dog in a scene from the movie "White Bim the Black Ear" based on the story by Gavriil Troyepolsky

Sputnik

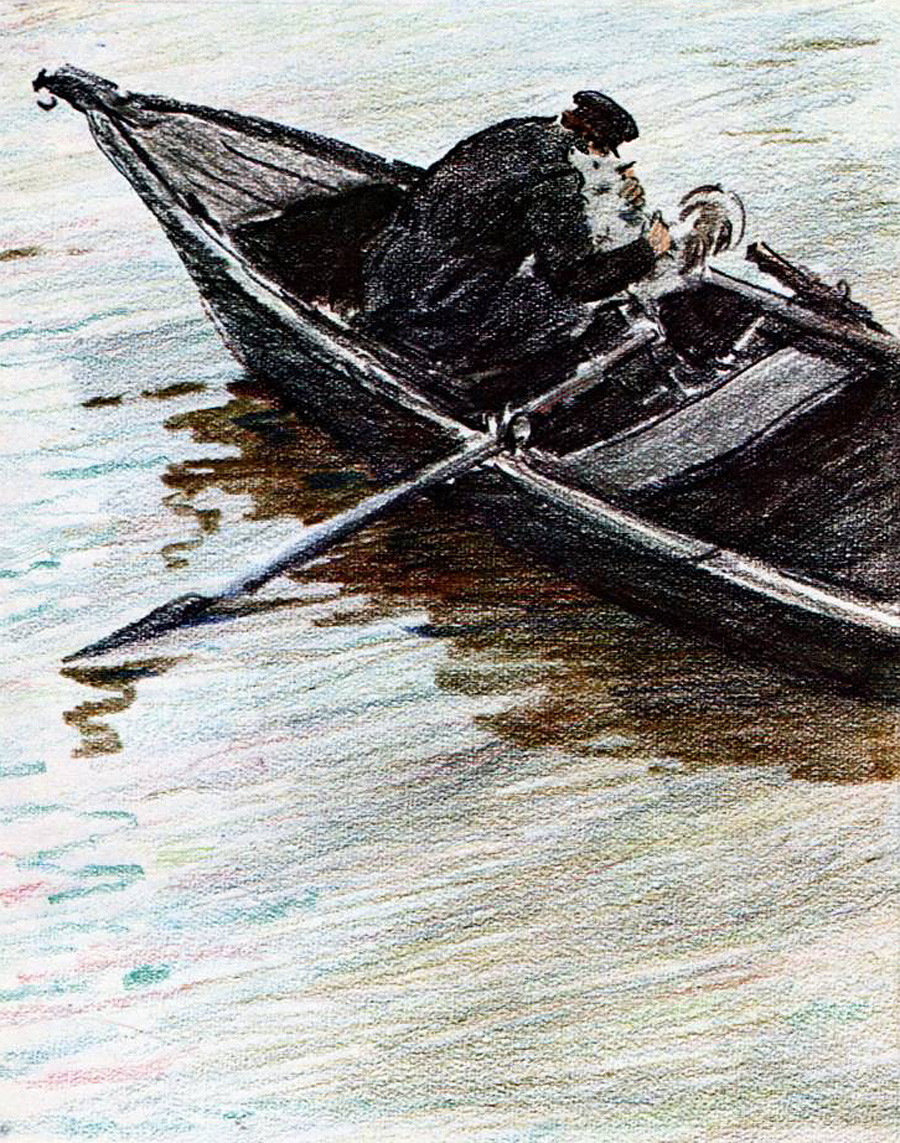

The illustration depicts poor Gerasim, a serf forced to get rid of his beloved dog Mumu, hugging her before throwing into the water.

Soviet Russia Publishing House / Igor Pchelko“Gerasim drowned Mumu” is one of the best-known phrases for children studying Russian literature and something everybody knows about Ivan Turgenev’s story Mumu (1854). In this mournful portrait of serf life in the Russian Empire, an inhumane lady orders her servant, forceful but deaf-mute and obedient Gerasim to get rid of the only creature he loves, a small dog called Mumu.

First, Gerasim tries to sell Mumu, whom he adores, at the market, but she gnaws through a rope and runs back to him, so the lady orders him to kill her. Sorrowful but unable to disobey, Gerasim drowns poor Mumu and leaves his lady forever. Thus, Mumu becomes an innocent victim of human brutality – the role that dogs, unfortunately, often play in Russian literature.

An illustration to Anton Chekhov's story "Kashtanka", a 1903 watercolor by D.Kardovsky

SputnikThe heroine of an eponymous 1887 story by Anton Chekhov, Kashtanka is an adorable small red dog, “a mix of a dachshund and a mongrel” living with a gloomy, heavy-drinking carpenter who beats and feeds her poorly. One day she accidentally gets lost. A stranger finds her and takes her with him.

He turns out to be a circus trainer and in his house Kashtanka meets the other animals: a cat, a goose and a pig. They all live together and the dog is quite happy – at least she lives better than she did at the carpenter’s. But one day, performing on the stage, she hears her old owner and his son shouting her name from their seats and runs back to them. Loyalty above everything!

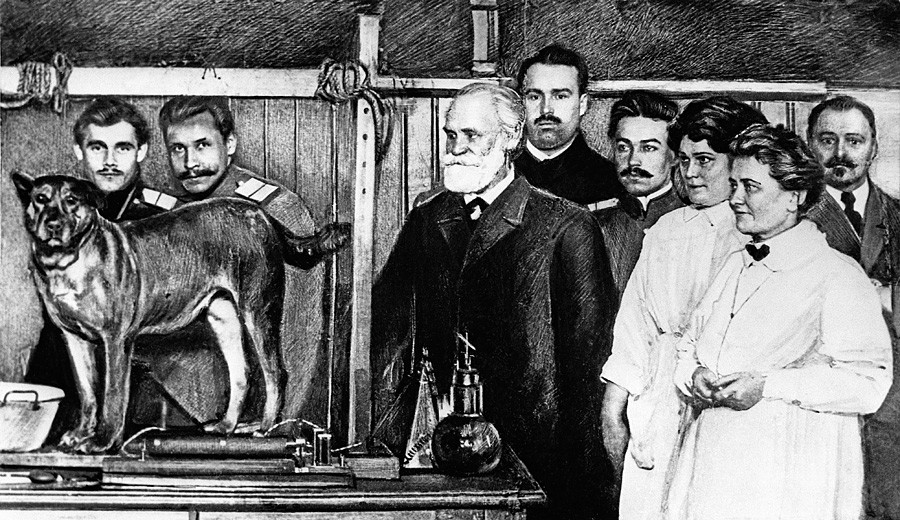

Ivan Pavlov and his colleagues from the Physiology department at the Military Medical Academy in Petrograd, 1914.

SputnikA devoted scientist and a Nobel laureate Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was appreciated both in the Russian Empire and in the USSR: his research greatly expanded the knowledge of human physiology. Nevertheless, his achievements wouldn’t have been so profound if it hadn’t been for his animal helpers – dogs.

Pavlov is reported to have been a caring man who never hurt a dog if he could help it and did everything to improve their living conditions. His most famous experiment concerning dogs touched upon the reflex system: Pavlov discovered that if you feed a dog after turning on a lamp, they gradually started to salivate after the light goes on even without food.

That led to a joke where Pavlov’s dog tells her companion: “Watch what I can make this old man do: as soon as I drool he’ll smile and write in his little book!” The term “Pavlov’s dog” became a symbol of self-sacrifice in the name of science. There are even monuments to Pavlov’s dog from grateful Russians.

Small Sharik before the operation that would turn him into a human.

Screenshot from Heart of a Dog movie, 1988A short novel by Mikhail Bulgakov (written in 1925) has a plot where a stray dog turns into a man – and the outcome shows that sometimes dogs are far more decent and polite beings than man. A prosperous professor Filip Preobrazhensky finds a poor hungry dog, Sharik, on a Moscow street, takes him home and puts him at the center of a mysterious experiment.

He manages to turn Sharik into a man, with organs donated by a drunk. The bold experiment ends up badly. Sharik, who was a kind and intelligent dog, gets corrupted by the hypocritical Soviet system, starts to drink and tries to slander his creator Preobrazhensky in order to get his apartment. Frustrated, Preobrazhensky makes Sharik a dog again. Perhaps sometimes it’s better not to be a human.

Belka, Stralka, their puppies and a couple of other dogs photographed in 1961. Belka is the 6th one from the left (black with the white forehead, standing), Strelka - the 8th from the left (white, standing).

V.Zhikharenko/TASSBefore Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in 1961, the USSR had sent numerous dogs to space in order to test whether a living creature could to survive the flight. All dogs were homeless mongrels raised by scientists, who treated them best they could, as they knew that their lives could end tragically.

That’s what happened to Laika who became the first living creature to orbit the Earth in 1957. Sputnik-2, her spaceship, was launched successfully but the space industry was at the time unable to bring her back, meaning little Laika died in space.

Nevertheless, Laika's tragic experience allowed researchers to improve Soviet spaceships. In 1960, the scientists sent into orbit two more dogs, Belka and Strelka. The two survived the flight successfully, staying in orbit for more than a day and going around the Earth 17 times. Belka and Strelka came back home and led long, happy lives in the space research institute. They deserved the rest after all: they, as well as many other dogs, paved the way to space for humanity.

People's Artist of the USSR Vyacheslav Tikhonov as Ivan Ivanovich, Bim's master, in a scene from "White Bim the Black Ear" directed by Stanislav Rostotsky.

TASSCreated by the Soviet writer Gavriil Troyepolsky who wrote the eponymous novel in 1971, White Bim the Black Ear is a Scottish Setter of unusual white color. Bim is raised by Ivan Ivanych, an old war veteran who, following the death of his wife, lives alone. After Ivan Ivanych falls sick because of an old war wound, Bim is left alone, confused and lonely.

He desperately tries to find his owner, meeting different people, good and bad. Some of them beat him and make him suffer. The others, on the contrary, help and treat his wounds. Finally, the dog dies in a shelter, just hours before Ivan Ivanych finds him. Though fictional, Bim became a sort of “Russian Hachiko” – a dog symbolizing fidelity and dedication.

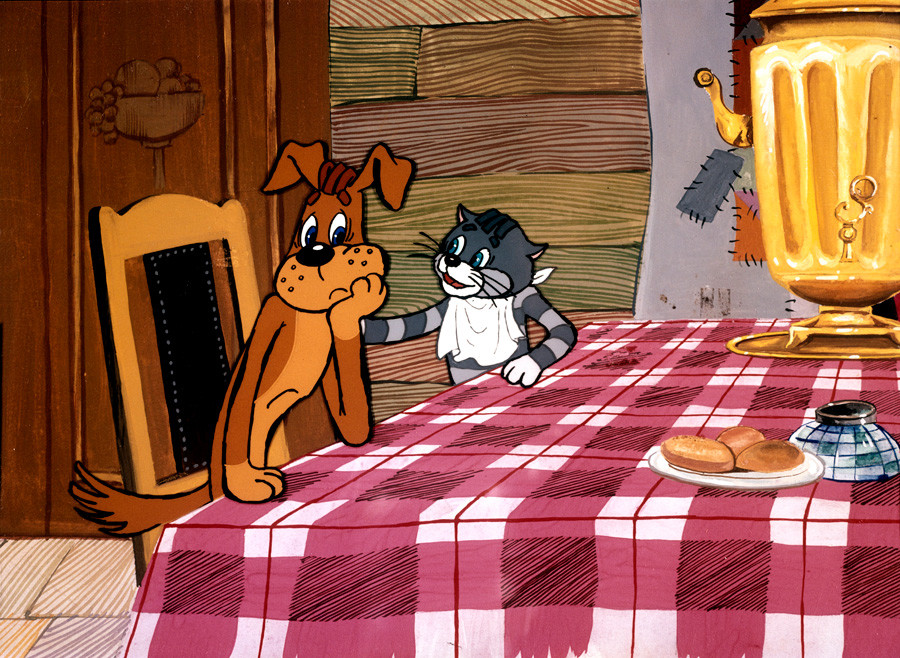

Sharik and his friend (or, rather, a frenemy) Matroskin the Cat. Practical and business-type Matroskin usually makes fun of Sharik, a hopeless romantic.

Global Look PressThis charming dog, a namesake of Bulgakov’s Sharik (this name means “a little ball” and is extremely popular for dogs in Russia), was created by children's author Eduard Uspensky and became a nationwide star after the release of the Three from Prostokvashino cartoon in 1978.

Sharik is one of the “three”, along with a clever boy nicknamed Uncle Fedor and Matroskin the cat; they all live together in Prostokvashino village. Unlike rational and businesslike Matroskin, Sharik is a hopeless romantic who is always getting into trouble.

For instance, he is keen on hunting but cannot stand the idea of killing animals so his friends give him “a photo gun”, a mix of a gun and a camera so he can “hunt” creatures without hurting them. Despite being completely disorganized, Sharik is a great friend, always kind, nature-loving and generous.

If you’re wondering “And what about cats?” – don’t worry. We have an article on the most important cats in Russia’s culture as well. Feel free to read it!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox