Many famous politicians and popstars, monarchs and presidents, poets and artists, movie stars and ballet dancers have stayed in the Metropol Hotel during its long history, from Bernard Shaw and Bertolt Brecht, to Michael Jackson, David Bowie, and Sophia Loren. The public is even welcome to view the stunning interior of the Metropol during a tour every Sunday.

“Several years ago we had an American writer, Amor Towles, who stayed in the Metropol for several months in order to write a book of fiction, ‘A Gentleman in Moscow,’ about a Russian aristocrat imprisoned to life in a small attic of the Metropol Hotel,” my Metropol guide for the day, tells me.

“The novel was published in 2016 and instantly became a bestseller in the U.S. From this point on, we have had dozens of American tourists every week coming with this book and trying to see the attic where the main hero lives, but we don’t have one, it’s an entire fantasy of the author. But even without the attic nobody leaves disappointed.”

There are many memoires, books, documentaries, and feature films dedicated to the Metropol all over the world and they all create a certain image of the place - sometimes far departed from reality.

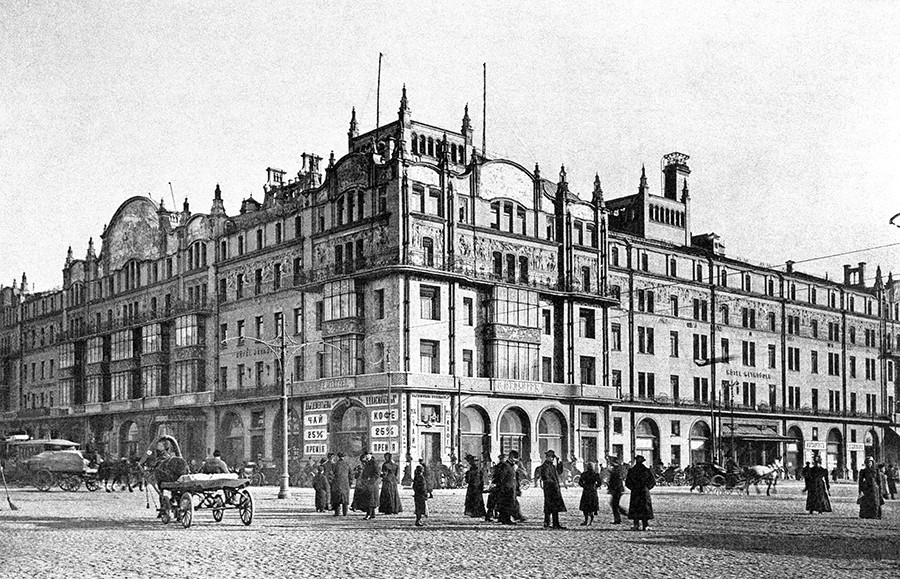

Funded by the Russian merchant Savva Mamontov, the hotel was built in 1905. Several architects worked on the project: Leo Kekushev, one of the best specialists on Moscow’s modern art scene, started the project. William Walcot, his British colleague, took over before a group of completely different architects took the helm and completed the iconic building.

No expenses were spared in making the structure rock solid. This was evident when, shortly after the Revolution, Russian junkers fighting the Bolsheviks used the Metropol as a stronghold due to its thick walls. They holed up in the hotel for an entire week before artillery fire forced them to surrender - but the structure survived relatively undamaged.

As legend has it, Mamontov was struck by a fascinating idea - he wanted to replicate Mikhail Vrubel's famous “Princess of Dreams” painting as a ceramic mosaic and display it for the public. The version of Vrubel's work, depicting a dying young knight and a princess hovering over him, is now on permanent display on the hotel’s exterior. It demonstrates one of Mamontov’s principles: To bring art to the streets.

Mamontov even wanted the hotel to be an opera house and envisaged the famous Russian singer Feador Chaliapin performing there, but sadly this never materialized.

About 80 percent of the hotel’s interior design dates back to the Russian Empire and has been carefully preserved. The luxurious fixtures and style that survived the 1917 Revolution and Soviet Union - largely thanks to the “hotel for foreigners” status is acquired early on - makes the places truly unique. The hotel has 351 rooms, both new and old.

“This chair and table were used by Michael Jackson, when he stayed here,” explains the guide, showing me one of the hotel’s largest modern suites. When the guests come to see this room, they often ask if they can sit in the chair. The room also has a piano used by Jackson; apparently he used it to compose his “Stranger in Moscow” track.

I asked my guide about the room where John F. Kennedy’s killer - Lee Harvey Oswald - once stayed. She was astonished. At that very moment - and by complete coincidence - we were standing right in front of that very room, number 2219. Oswald had asked for Russian citizenship but had no luck, he then tried to commit suicide before spending three long months in the room waiting to see if his reapplication would be successful.

There is a cozy, elegant room, made in green and gold tones. The room boasts a view of the Bolshoi theatre, world-famous Russian ballerina Diana Vishneva's favorite establishment. When she comes from Saint Petersburg to Moscow to perform at the Bolshoi theatre, she often stays there. There are many more rooms in the hotel kept warm for their regular visitors.

Some rooms even have important historical value. Room 2217 is a legendary place, in which the first constitution of the Soviet Union was written. The people working on it were locked in there by Yakov Sverdlov and did not have the right to leave without finishing it. The work was done in a few days.

If you want to have a look at the hotel rooms, hideouts and more, the Metropol is open for everybody: You can come to the excursion that takes place every Sunday (Teatralniy Proez

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox