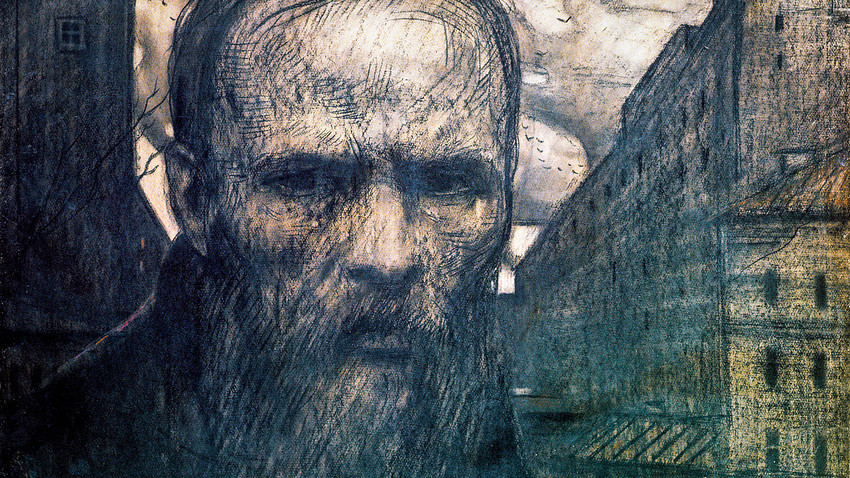

Portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky by Vasily Perov

State Tretyakov Gallery“I’ve re-read all of Dostoevsky over the past three months. And I feel nothing but almost physical hatred for the man,” the Russian politician Anatoly Chubais said during an interview with the Financial Times in 2004. Chubais, a famous liberal, would love to “tear Dostoevsky to pieces” for “his idea of Russians as special, holy people, his cult of suffering and the false choices he presents.”

Anatoly Chubais.

Konstantin Kokoshkin/Global Look PressChubais doesn’t speak for all Russians, of course, but he is not the only person who regards Dostoevsky as toxic and dangerous. But what is it about the great writer that makes him so controversial?

Ernest Hemingway respected Dostoevsky but found his style hard to deal with.

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, BostonDostoevsky’s critics point to two main arguments. The first touches on his alleged lack of style. “’Poorly written’ is the main claim Dostoevsky himself hears about his books,” journalist Sergei Lebedev wrote on TheQuestion (Russia’s Quora). “Tolstoy thought so, emphasizing that some of Dostoevsky’s novels are weak and ‘not perfect in terms of technique.’”

Compared to Tolstoy’s rich and flamboyant prose, some of Dostoevsky’s works really do look weak stylistically. Sometimes his novels even contained sloppy mistakes. For instance, in Crime and

This happened in part because Dostoevsky had money problems and was forced to write his works quickly to make ends meet and stave off creditors. He complained ironically about this: “If I was paid as much as [Ivan] Turgenev [another great author from that period], I would certainly write just as good!”

Of course,

A scene from the Soviet ecranisation of Crime and Punishment (1969): Raskolnikov near the dead body of a woman he killed.

KinopoiskTaking into consideration Dostoevsky’s popularity, many feared that his novels provided a perverted depiction of Russians. Maxim Gorky, a famous writer of the 20thcentury, wrote: “Dostoevsky surely is a genius but an evil one. He felt, understood and portrayed with pleasure two sicknesses of a Russian man nurtured by our ugly history…the sadistic violence of a nihilist who’s lost faith in everything and the masochism of a downtrodden creature…but this is not everything that we have, there is something more than beasts and thieves inside us! And Dostoevsky saw only them.”

As a socialist writer, Gorky had his reasons for disliking Dostoevsky, an Orthodox monarchist, but other authors with views completely opposite to Gorky’s have expressed similar thoughts. Vladimir Nabokov, who emigrated from Russia right after the 1917 revolution, said in his lectures that Dostoevsky’s “gallery of characters consists almost exclusively of neurotics and lunatics.”

“I do not like this trick his characters have of ‘sinning their way to Jesus’ or, as the Russian author Ivan Bunin put it more bluntly, ‘spilling Jesus all over the place,

Vladimir Nabokov harshly criticized Dostoevsky.

Fred Stein/Global Look PressNabokov did not mince words in criticizing Dostoevsky and also listed among his sins creating “the ultimate formula of egoism-Antichrist-Europe on one side and brotherhood-Christ-Russia on the other,” thus dividing Russia from the West and presenting it as a God-loving holy nation whose purpose is to save the world with Orthodox Christianity.

In Dostoevsky’s works, Russia is a conservative milestone protecting the world from moral decay. There was no love lost between Dostoevsky and pro-Westerners or liberals of his time. “Our Russian liberal is a flunkey before everything, and is only looking for someone whose boots he can clean,” he wrote in The Possessed. Unsurprisingly, to this day many pro-Western liberal Russians (like Chubais) dislike Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky's monument nearby the Russian State Library in Moscow.

Vladimir Astapkovich/SputnikNevertheless, all the weaknesses in Dostoevsky’s work do not outweigh the merits, and so the author remains beloved by millions of readers, even if they don’t share all his beliefs. Many famous international authors are fans as well. For example, the American author Jonathan Franzen said he “went to school on Dostoevsky.” The Turkish Nobel-prize-winner Orhan Pamuk is sure that “Dostoevsky is an author with whom I tend to identify. I have learned a lot from him.”

Perhaps the best recommendation Dostoevsky was given came from another great Russian novelist: Leo Tolstoy himself. They never met each other and had vastly different views, but when Dostoevsky died Tolstoy wrote in his diary: “Now I lost some kind of a moral pillar…I got confused and then understood how dear Dostoevsky was to me and cried, and I’m crying right now.”

Dostoevsky's worlds were dark and grim - and not everyone in Russia liked it.

Pavel Balabanov/SputnikYou know who was even a harsher, more badass author than Dostoevsky? Tolstoy. Just read how he fought against all the powers-that-be he ever knew.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox