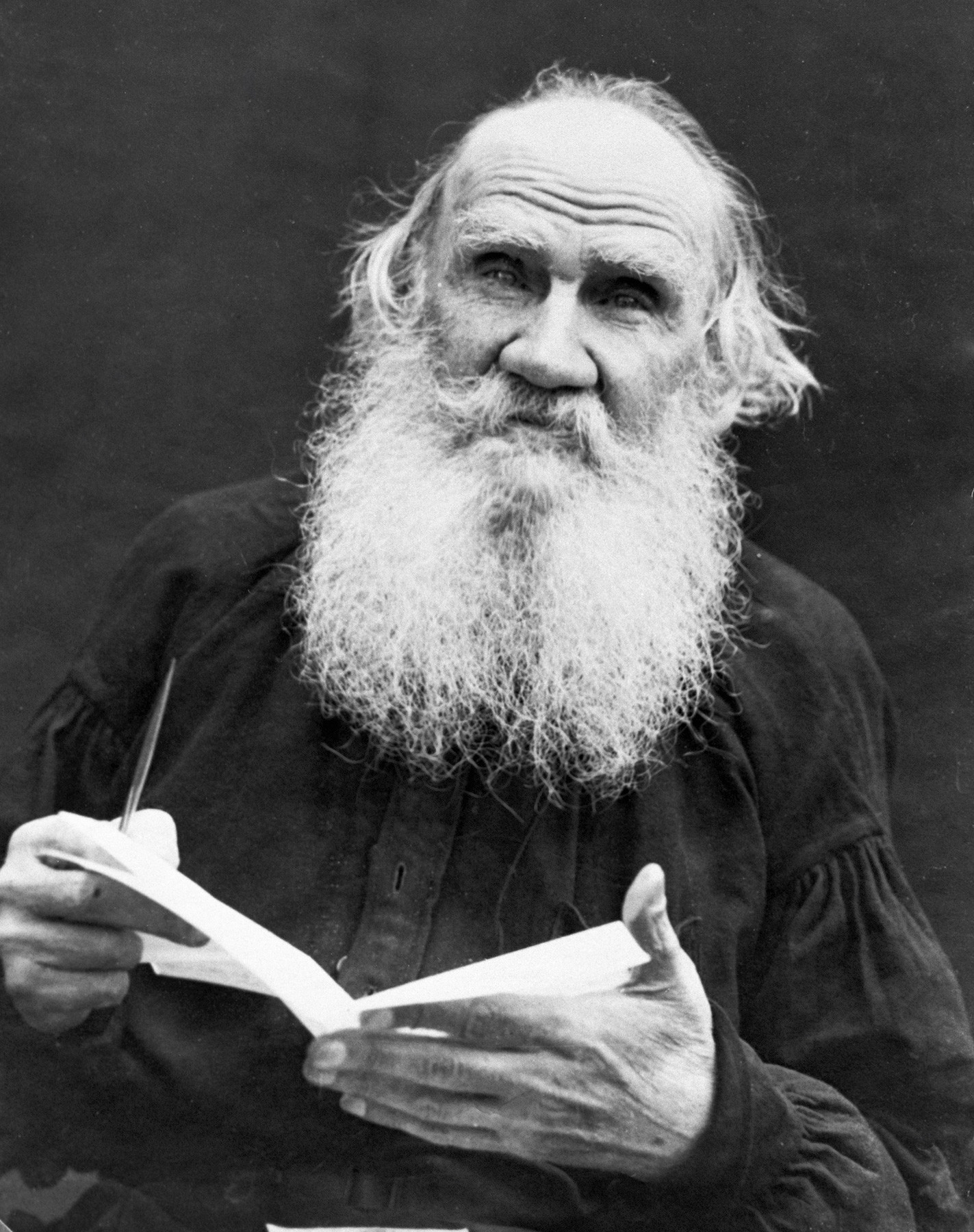

“War and Peace” is so full of rambling sentences that you forget the beginning by the time you come to the end. Even more, for every

Most of Tolstoy’s moralism comes in stark contradiction with the life he led. An unstoppable gambler in his youth, he spent his whole life as an avid womanizer (though he detested himself for it). Most of his children were angry with their father for depriving them of fortune, and the story of his relationship with his wife Sophia is full of quarrels, tears, and other women. Is he the guy to teach his readers ethics? Meanwhile, each Tolstoy novel and story has a moralistic ending.

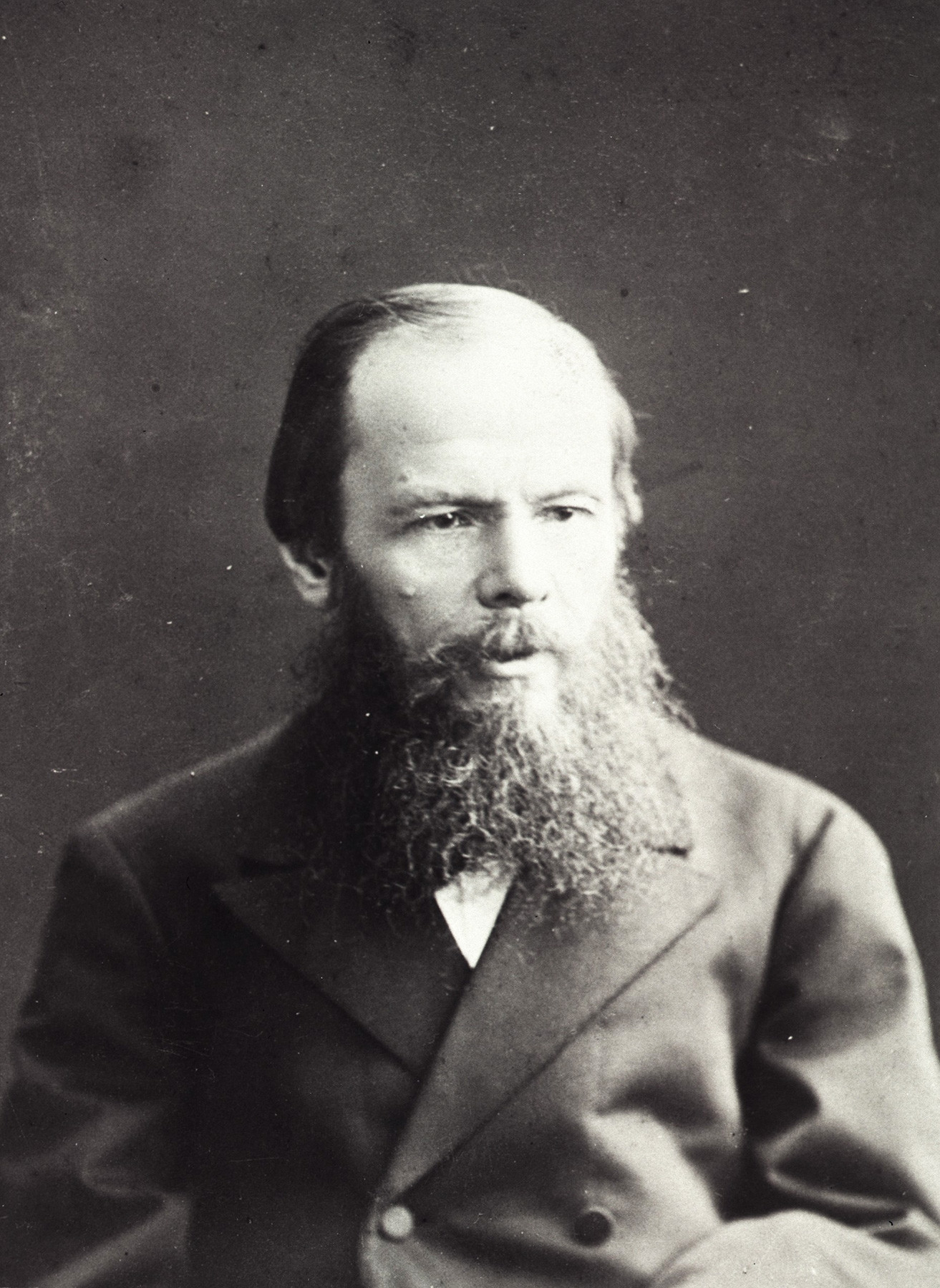

“An oval table of a round form in front of the sofa” - that’s him, in the very first chapter of “Crime and Punishment” (a line bashfully edited in all English translations). Russian editor of the novel, Mikhail Katkov, brought the author’s attention to this mistake. Dostoevsky thought for a while, and said: “Just leave it as it is”.

And the 19th-century translators of Dostoevsky knew better: for example, “The Grand Inquisitor,” a poem in prose that relates the author’s view on Christian philosophy and life in general, was usually edited out of the novel as “excessive”.

And the endless speeches of Prince Myshkin in “The Idiot” – wouldn’t you be surprised to learn that they are so long because Dostoevsky’s novels were published in literary journals that paid him by the line – so the longer the writing, the more he’d be paid. Well, he didn’t write most of them anyway in his handwriting; his wife and secretary, Anna Dostoevsky, did it. This didn’t stop Fyodor the gambler from selling their wedding rings and her wedding dress to pay a gambling debt in Europe.

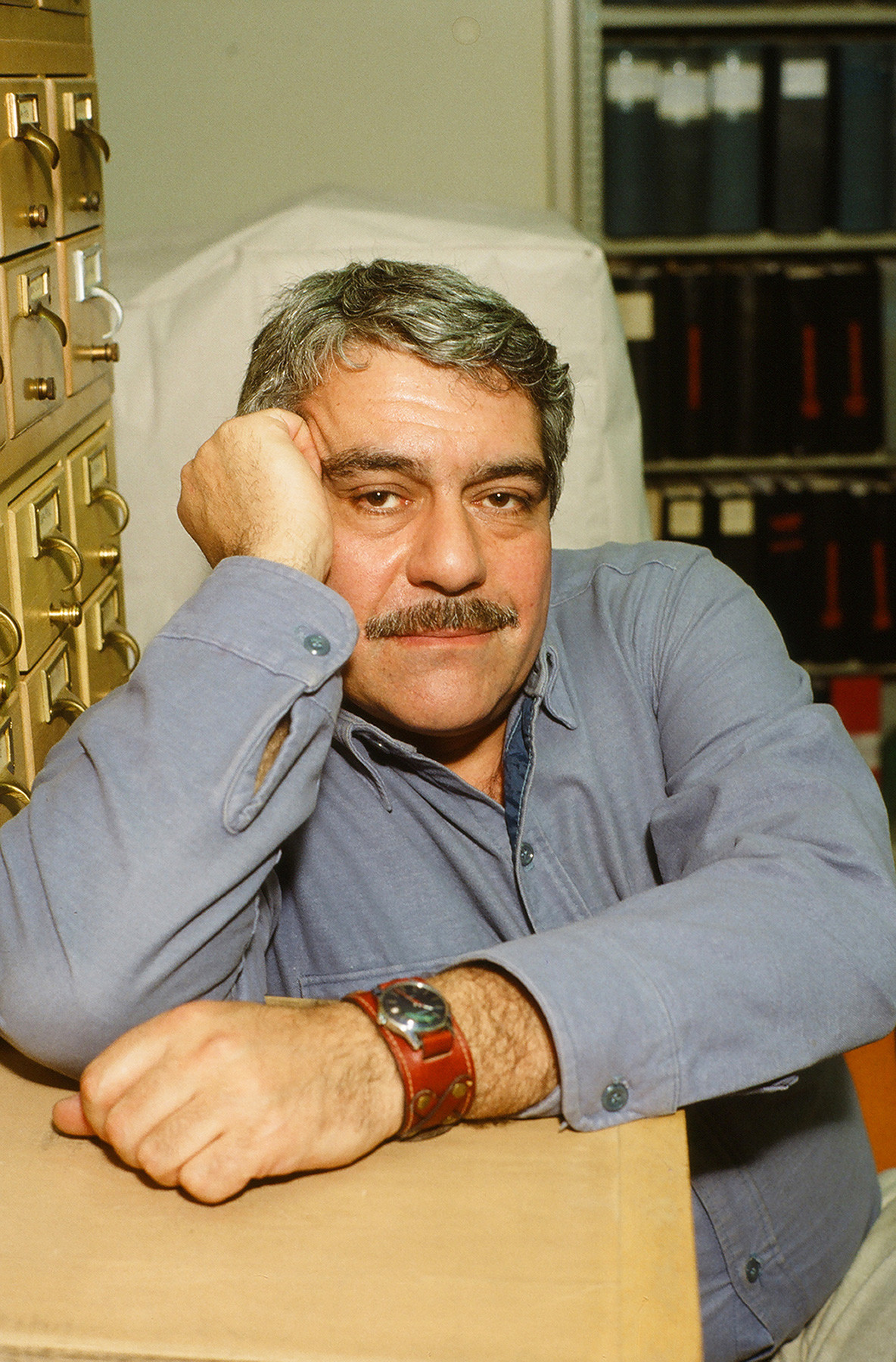

During his life, Mikhail Bulgakov wasn’t named among the best Russian writers. Initially, he received a medical education and worked as a doctor. Coincidentally, his literary work started shortly after he developed a morphine habit during the Russian Civil War (1918 - 1921).

Most of his works were short stories and plays, and fame first came to him when Stalin liked his play, “Days of the Turbins”, first staged in 1926. But during the 1930s, Bulgakov was in jeopardy. Bulgakov tried to flatter the tyrant again by writing a play dedicated to Stalin’s youth, but Stalin didn’t like it and ordered the staging to be canceled. After that, Bulgakov’s health rapidly deteriorated, leading to his premature death in 1940.

During the 1930s, Bulgakov secretly worked on the novel, “The Master and Margarita”, while at the same time abusing morphine – stains of the drug have been found on the novel’s manuscript decades later. The novel became famous only years after his death and overshadowed the writer’s other works – most of the world’s readers don’t remember his “Morphine” (‘A Young Doctor’s Notebook’), an early account of a junkie village doctor’s life; or “Heart of a Dog,” a story about genetics intertwined with politics in the early years of the Soviet state. Meanwhile, “The Master and Margarita”, despite all the praise it has gotten over the years, is a novel with a flappy plot, heavily relying on worn-out “mystical” images, apparently inspired by the writer’s delusional state. The novel’s imagery draws heavily from German expressionist literature, most notably novels of Gustav Meyrink, one of Bulgakov’s favorite writers.

One of many Russian/Soviet writers who didn’t get published in the USSR because of the

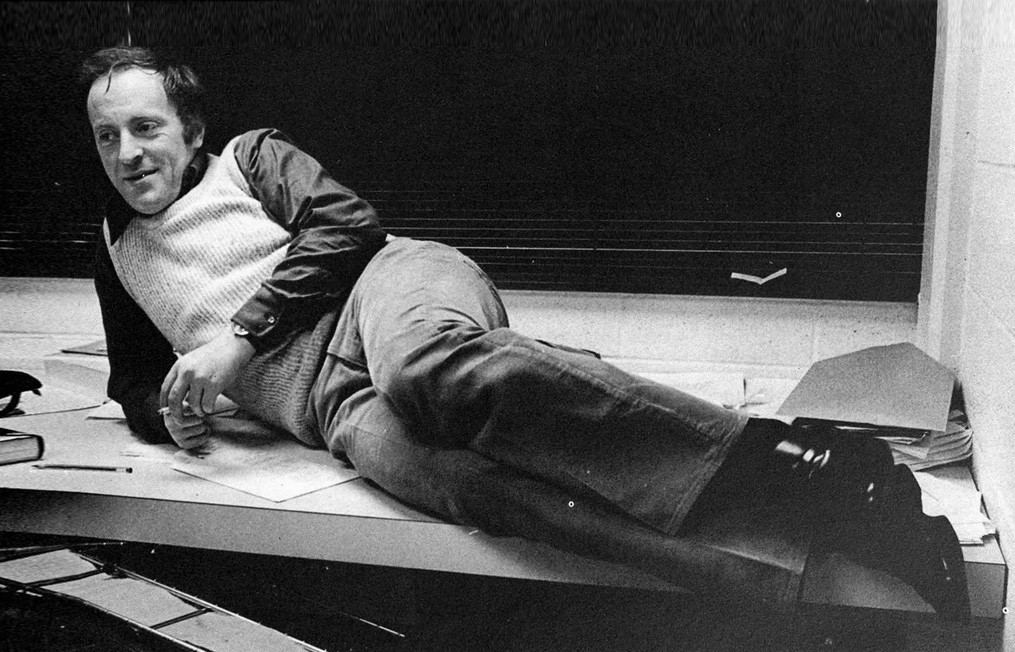

First of all, Dovlatov didn’t write fiction. His short stories, maybe better say sketches, were modified excerpts from his own daily life, spiced with bitter humor and sad recollections of a loser’s past and present. In the realm of the Russian language of the 20th century, there were far greater exploits in that field, beginning with Mikhail Zoschenko, author of humoristic sketches that were extraordinarily popular among Russians for their witty humor and neat composition.

In Russian, Dovlatov’s prose is mostly interesting for the contemporary vernacular he recreated, lost or rendered far less intriguing by translation. In Russian, however, his prose becomes obsolete because the reality he described is no longer relevant. So, Dovlatov is best left for those who just love his style – but he can hardly be perceived as a writer who defines Russian literature.

Drifting away from the lyrical matter in his poems, in later years the ‘American’ poet Joseph Brodsky (he liked to identify himself as such, and even changed the spelling of his original name – Iosif) turned his poems into a tangled web of intertext and obscure allusions (see “Vertumne,” or “Centaurs I-IV”), which is hardly decipherable for a reader less proficient in world literature than Brodsky himself was – and that means just about every reader! But poetry is not a lecture on the history of literature, and Brodsky thought and propagated just that. This made us all love his early, sincere and heartfelt poems, more than the tired-of-the-world lyrical persona of his later years.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox