The Orthodox believers in Russia never lacked saints to worship.

Public domainHow does one become an Orthodox saint? There are only two checkboxes: first, the candidate must live a righteous life full of heartfelt concern for one’s neighbors. Second, he/she must be dead. A deceased righteous person who has contributed to the spread of Orthodoxy, faithfully served God, and worked miracles or become a martyr for the Christian faith can be elevated to sainthood by the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC).

“In the eyes of the ROC, saints are those who, having cleansed themselves of sin, have acquired the divine grace of the Holy Spirit and manifested His power in our world,” explains Archimandrite Tikhon Sofiychuk, chairman of the Commission for the Canonization of the Kyiv Diocese. The criteria for canonization are broad – it is not necessary to heal the sick with the touch of one’s hand, but merely to lead a virtuous life.

Over the years of its existence, the ROC has canonized over 2,500 individuals. Some, however, are more well-known among the Russian public than others. Who are they?

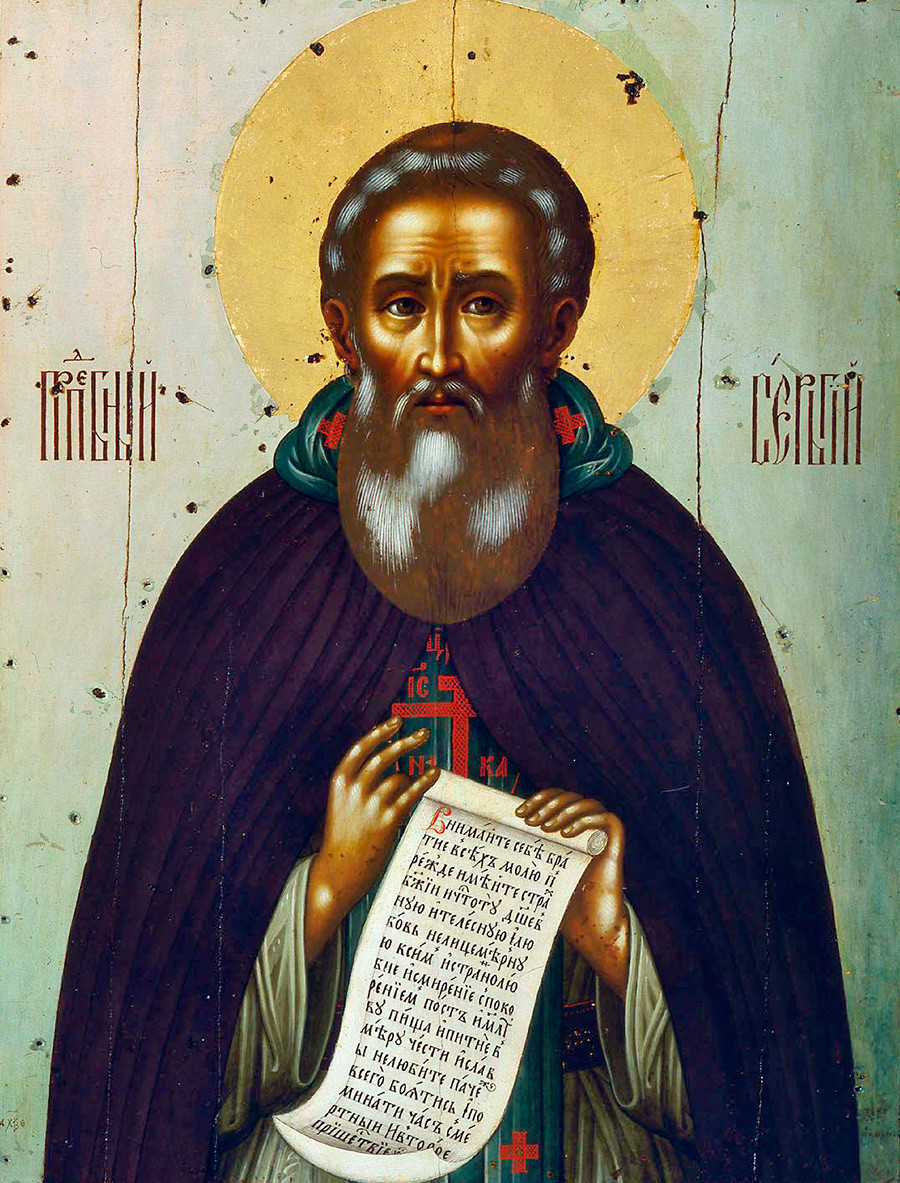

Monk Sergius of Radonezh lived at a time when the concept of “Russia” did not yet exist – in the 14th century when dozens of principalities vied for supremacy in what is today the western part of the country. Father Sergius, who wielded tremendous authority, was the first elder in Russian history to depart this world as a simple monk, one whom the powers-that-be came to for advice.

It was Sergius who founded (and later had his name attached to) the largest Russian Orthodox monastery, the Trinity Lavra of St Sergius. And it was he who, according to the annals, blessed Moscow Prince Dmitry Donskoy before the decisive Battle of Kulikovo Field against the Tatars, a seminal moment in Russian history.

Indeed, the very birth of Russia as an Orthodox nation is associated with the name of Sergius. “The emergence of Russian spiritual culture and Russian culture in general, Holy Rus as a cultural ideal... are unequivocally connected with St Sergius,” stresses Vladimir Legoyda, chairman of the Holy Synod Department of the Russian Orthodox Church for Public and Media Relations.

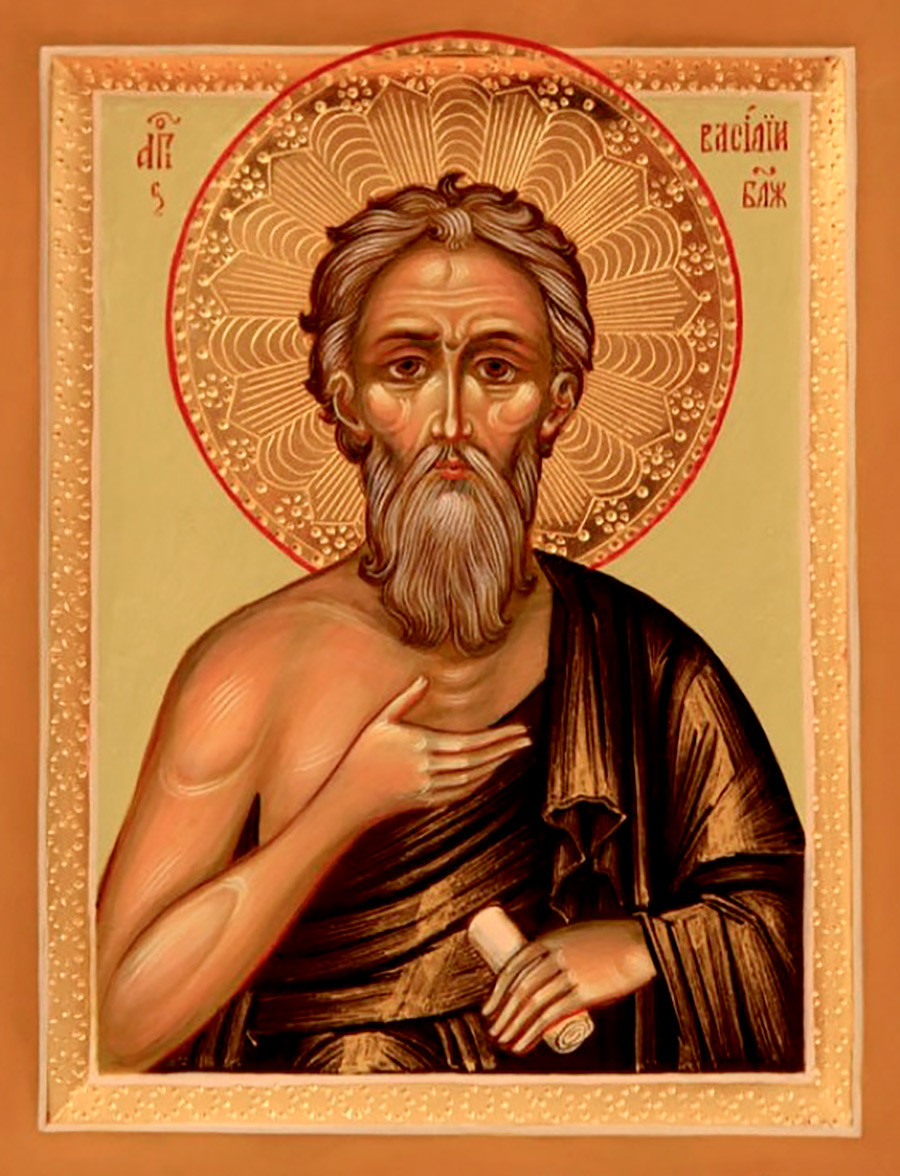

The Orthodox Church has a deep respect for holy fools who, despite their apparent madness, are enlightened spiritually and considered close to God. The champion of champions in this regard is Vasily the Blessed (a.k.a. St Basil).

The wandering Vasily wore rags all year round and had no home, yet the whole of Moscow knew and revered him. Believed to be able to foresee the future, the holy fool mercilessly cursed sinners and aroused the fear and respect of even the ruthless Ivan the Terrible. After his death, Vasily’s remains were buried on Red Square in the Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos – which these days you might know better as St Basil’s Cathedral, though it's not an official name.

Like Vasily the Blessed, Xenia of Petersburg was not of this world. According to the hagiographical records, after the death of her husband she started wearing his clothes, introducing herself in his name, and telling everyone that he was alive and well, and that it was she who had died. Xenia distributed all her wealth to the poor and wandered around the city, begging for alms. At night she prayed to God.

“For her great exploits and patience, the Lord glorified his chosen one during her lifetime. God’s servant Xenia was granted the gift of predicting the future and seeing inside people’s hearts,” remarks Sister Taisia in the hagiography of Xenia of Petersburg. She died after 45 years of wandering.

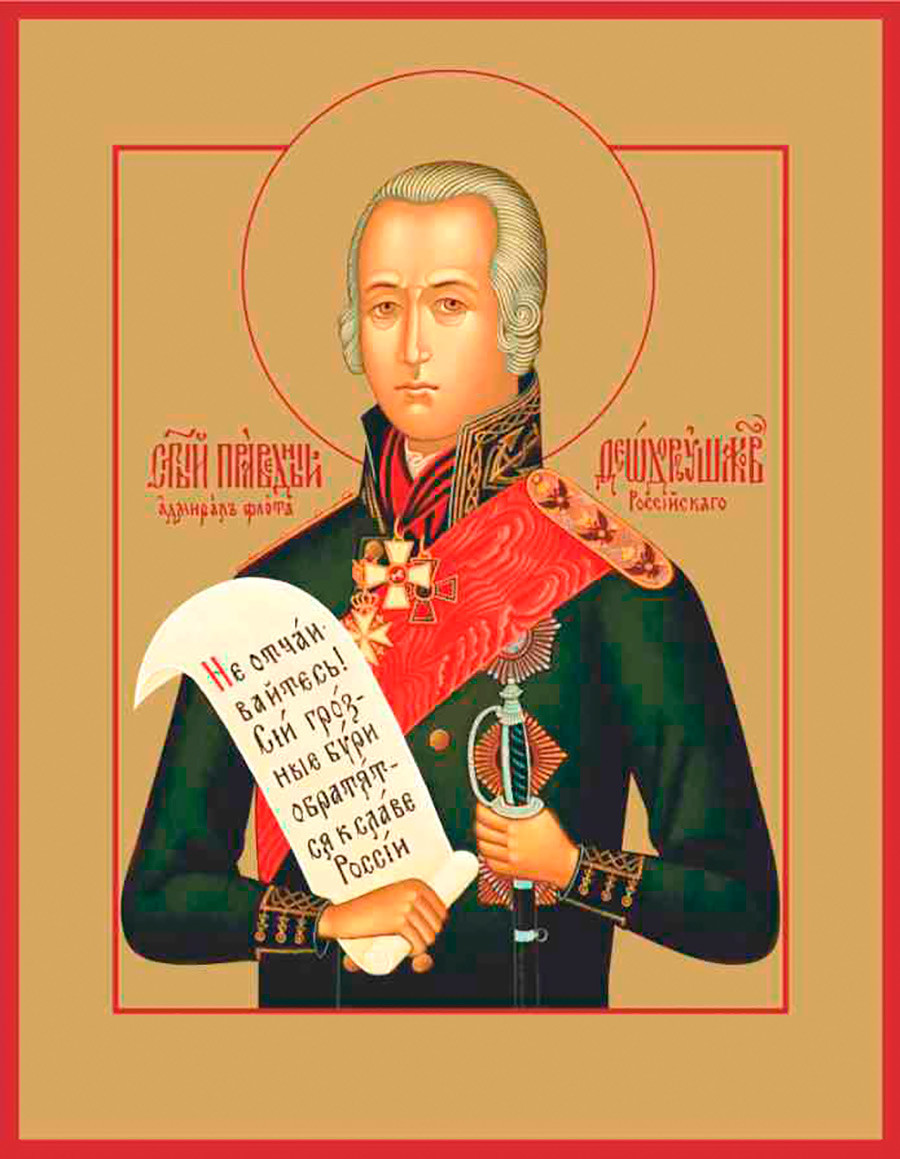

It is unlikely that Admiral Fedor Ushakov, a famous 19th-century naval commander, would have expected to become a saint almost two centuries after his death. Neither was he short of victories in his own lifetime. During his entire career, Ushakov did not suffer a single defeat, did not lose a single ship, and never had a subordinate captured by the enemy. Thanks to Ushakov and his genius, Russia dominated the Black Sea.

His merits were spiritual as well as military. For instance, he strongly opposed drunkenness among sailors, gave away all his wealth to charity, and spent many long hours praying in monasteries. “The strength of his Christian spirit manifested itself not only in his glorious victories for the Fatherland, but also in his great mercy,” reads the statement on his canonization. Since 2004 Admiral Ushakov has been the patron saint of the Russian fleet.

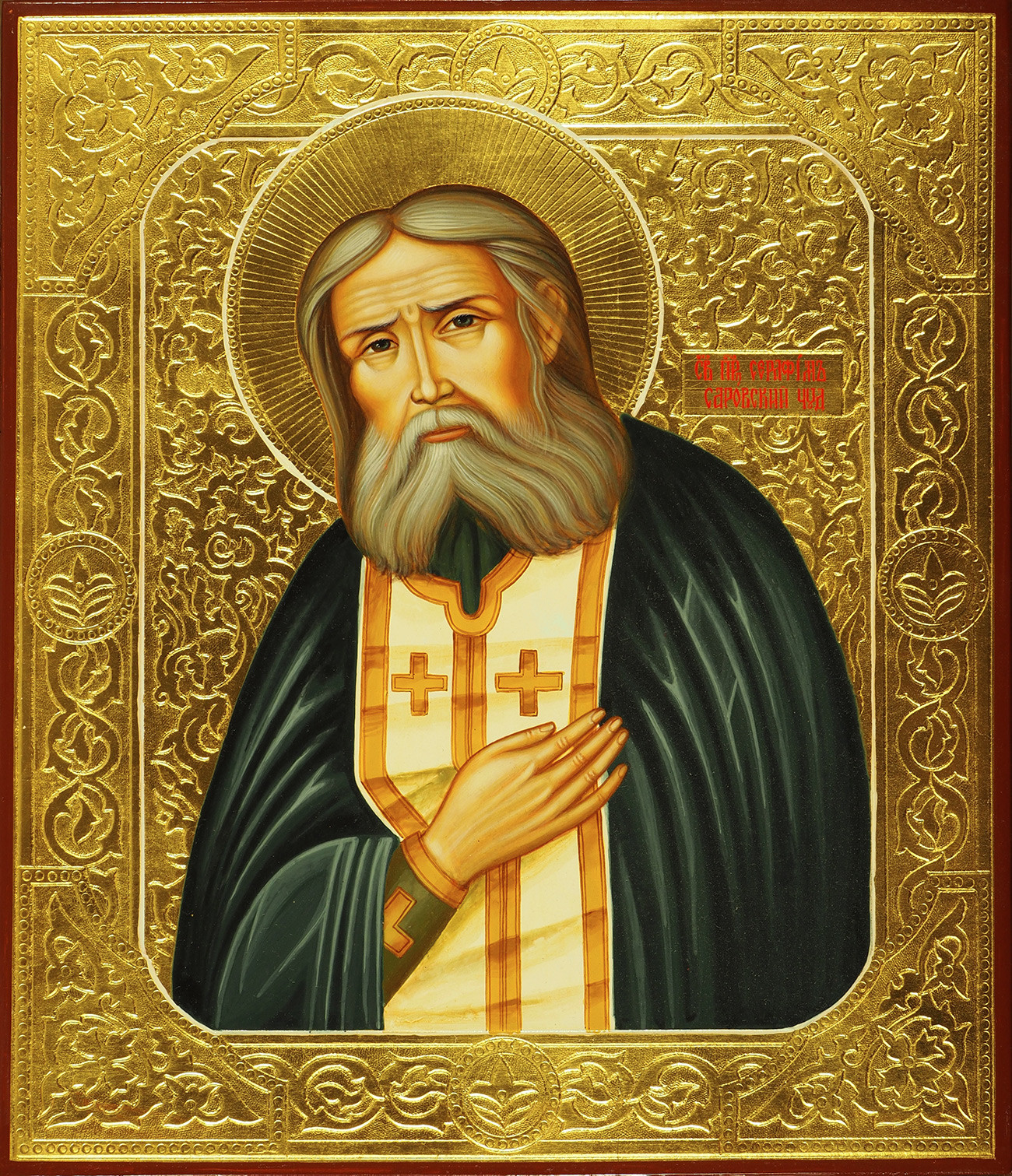

The spiritual heir of Sergius of Radonezh, the elder Seraphim of Sarov also lived a detached existence – in a forest, yet that did not stop people from all over Russia actively seeking out his company and advice. According to his hagiography, even bears and wolves bowed down before the elder’s goodwill (a slightly more plausible legend says that Seraphim was once attacked by robbers who broke his skull with an ax, after which the righteous man prayed only for them to see the error of their ways).

The veneration of Seraphim of Sarov began during his lifetime, but he was canonized only in 1903, at the initiative of Nicholas II, who hoped that the saint would provide him with a male heir. As Minister Sergei Witte wrote, the emperor and his wife “were sure that Seraphim of Sarov would give Russia a male heir after [the birth of] the four Grand Duchesses.” The imperial couple’s next child was indeed a boy.

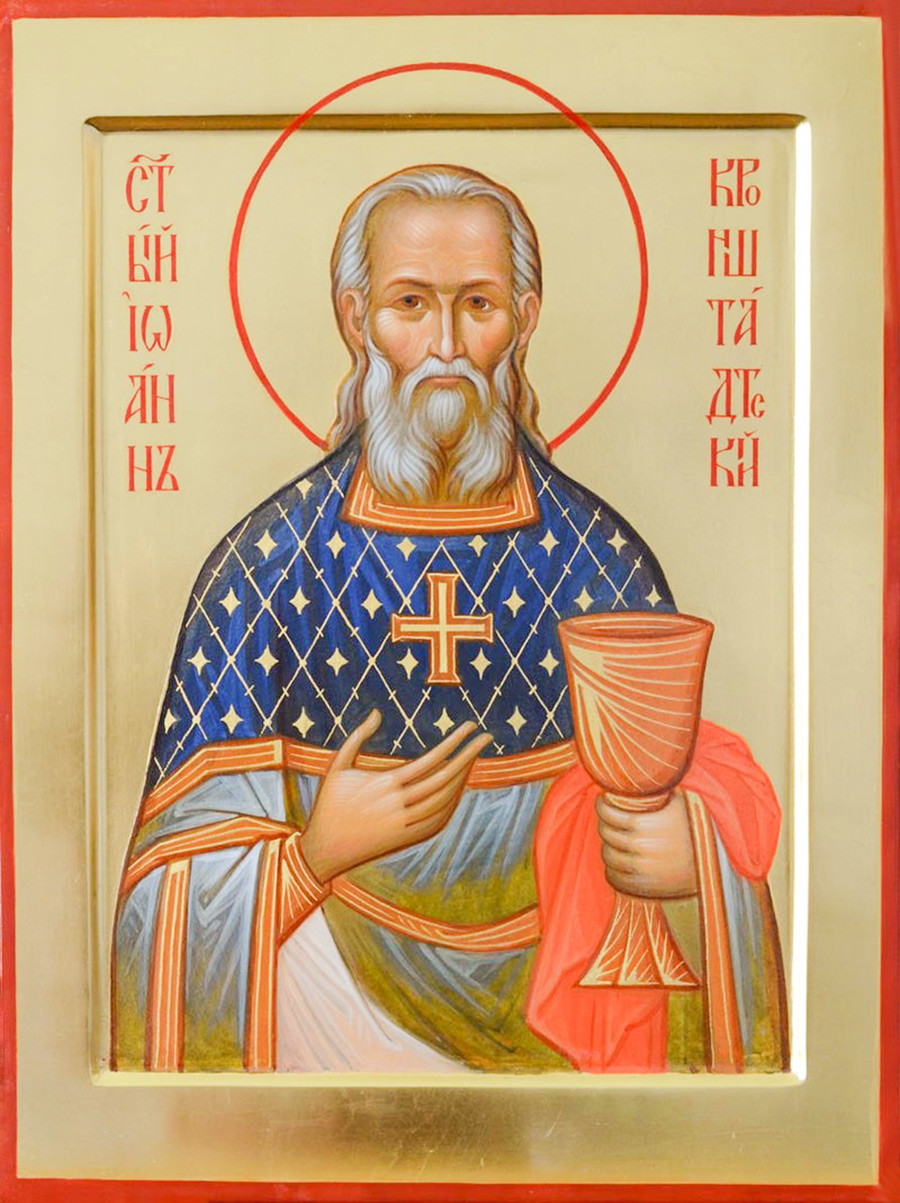

Unlike many other saints, John of Kronstadt was not a monk, but a parish priest. He lived near St Petersburg, believing, according to one biographer, that its inhabitants “know Christ no more than the savages of any far-flung Patagonia.” Father John settled in the Petersburg suburb of Kronstadt, a den of menial laborers, prisoners, and drunkards.

In the face of appalling conditions, he did all he could to strengthen the faith of his compatriots: he preached, healed, and assisted financially. Little by little, the priest turned into a star – so much so that it was he who laid to rest Alexander III after the tsar’s premature death. To the end of his days, Father John remained a supporter of autocracy and right-wing conservatism – even his love for humanity did not prevent him from hating those he considered enemies of the Orthodox faith.

The peasant woman Matrona was blind from birth, and unable to walk from the age of 16, yet, according to her hagiography, “she never murmured about her illness, but humbly bore the heavy cross given to her by God.” Like other saints, during her lifetime she became known among the Orthodox faithful, who came to her for advice or healing.

Moreover, she lived most of her life during the Soviet period, when the atheistic authorities forbade the practice of Orthodoxy, forcing Matrona and her lay sisters to wander from apartment to apartment, risking arrest. In the end, however, the Soviet government left her alone. This blind righteous woman remains one of Russia’s most popular “folk” saints, to whom people pray during illness or hard times.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox