And the winner is...

Getty Images; TASS; Global Look Press; Legion mediaWe, Russians, carry an enormous burden imposed on us. The burden of two bearded men sitting on our shoulders. Leo Tolstoy sits on the left shoulder and Feodor Dostoevsky on the right (or vice versa), and their colossal literary heritage crushes us to the ground. We have to carry them with us wherever we go and until we die.

This is how we feel, culturally speaking – a second after we meet any foreigner who is even a bit familiar with Russian literature, we always hear: “Oh, Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy…” Sure, those two are geniuses but the sad thing is that they, with the size and depth of their novels, completely outshine the other talented Russian writers in the quest for the global audience. And it is a shame.

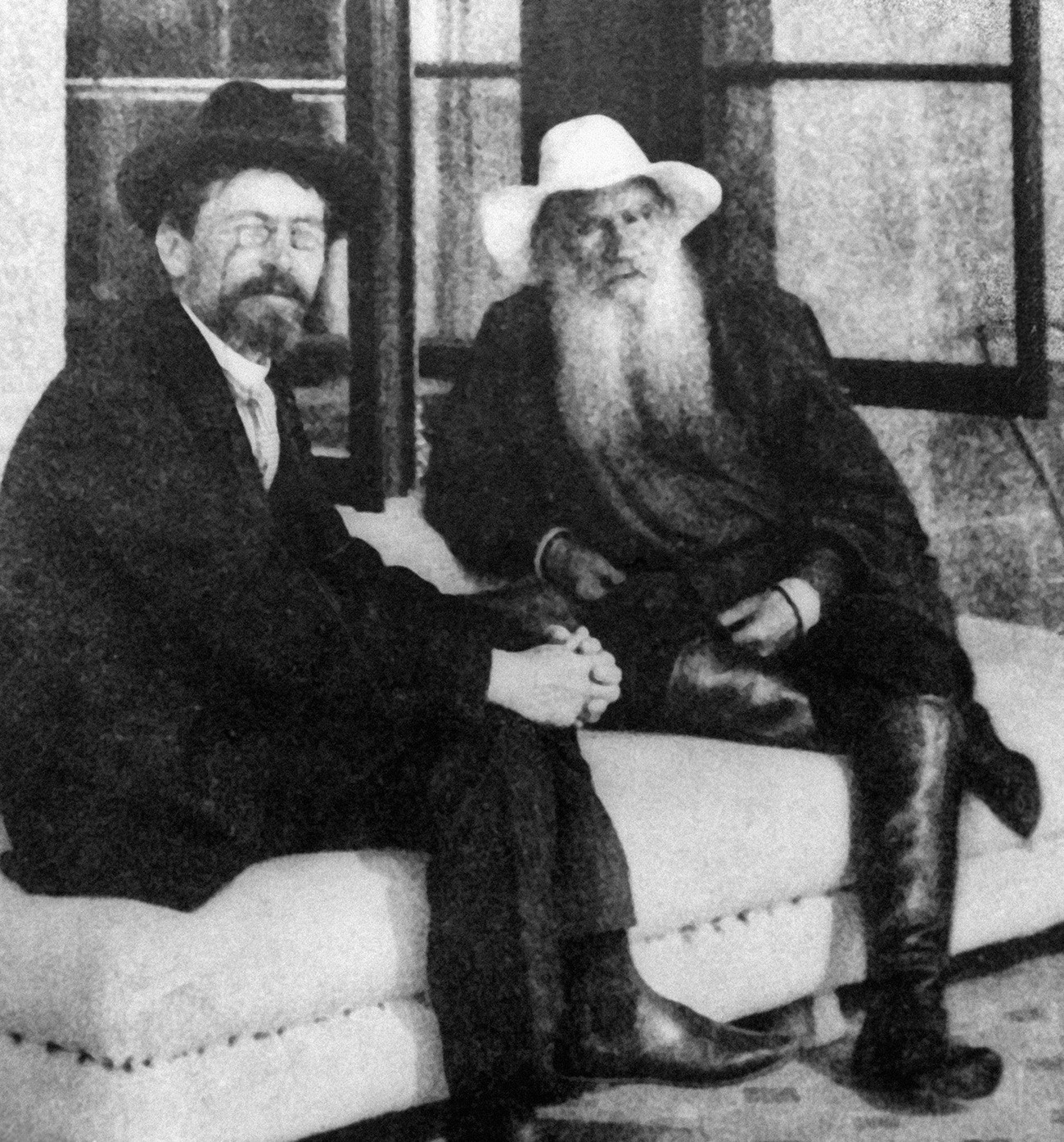

I know at least one author who, in my opinion, hands down wins the competition with Tolstoevsky, which is how those two authors of DEEP ALL-EMBRACING SPIRITUAL books are nicknamed together. The name of this badass fella is Anton Chekhov. In five reasons I’ll prove to you that Chekhov is far cooler.

Chekhov and Tolstoy in Crimea. They actually were on good terms.

SputnikI know the length of a book is a strange criterion to judge its quality by: there are sh*tty long novels (50 Shades of Gray is pretty big), as well as sh*tty short stories and brilliant books of any size. But for Russians this is personal.

Mainly, we get acquainted with our golden-classic-read-before-you-die books at school. When you have to wade through the four volumes of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, somehow combining it with studying other subjects, you really hate his guts... sorry, I mean, you appreciate the brevity that Tolstoy (and Dostoevsky, to a lesser extent) lacked.

Chekhov, on the other hand, is the LeBron James and Lionel Messi of short stories. Several small details and a few witty lines are enough for him to depict the whole life story of a character that Tolstoy or Dostoevsky would have rambled on for 10 pages. After all, it was Chekhov who said the phrase that Russians use as an analogue of “Brevity is the soul of wit” – “Brevity is talent’s sister”.

Russian literature surely lacks nothing heartbreaking, but different from the way Chekhov approaches the matter. The characters of Tolstoevsky suffer so much, so complicatedly and in such a high-browed manner (which was common for the 19th century), with so many thoughts of God, love and the Russian soul that it gets kind of boring. Woody Allen’s 1975 film, Love and Death, was brilliant in mocking it: “To love is to suffer. Not to love is to suffer. To suffer is to suffer...”

Feodor Dostoevsky, the all-time champion of Russian suffering.

Vasily PerovChekhov, unlike Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, shows his readers not as heroes akin to biblical ones, but as ordinary people. His characters usually are petty, laughable and bored, but they are daydreaming about a better world, yet stuck in their lives. (If it doesn’t remind you of yourself you’re a happy person and probably don’t need Russian literature.) We all are Chekhov’s heroes and hardly can be Tolstoevsky’s, unless you killed an old lady with an axe or defeated Napoleon.

Chekhov’s entire emotional spectrum can be best represented in his ironic quotation: “Such a beautiful day today. Don’t know if I should drink a cup of tea or hang myself.” Sounds pretty much like another day in the office.

Chekhov, looking relaxed and chilled as always.

SputnikBoth Dostoevsky and Tolstoy had their sets of values that they were more than happy to put in readers’ heads: hardcore Orthodox Christianity spiced up with conservative monarchism in Dostoevsky’s case, and radical Gandhi-like (actually, it was Gandhi who learned from him) peaceful anarchism in Tolstoy’s. It doesn’t mean that those concepts dominated their prose, but it is there and for those who don’t like sermons, that’s tough.

A friend of mine says, “When I read Tolstoy, I feel like someone is grumping at me, and though he is grumping all the right words, it’s still annoying.” This doesn’t happen with Chekhov because he never preaches anything but dignity, patience and humor. A quotation from his letter to his sister: “One must be prepared for anything and consider everything to be inevitably essential, as sad as that may be.” This pretty much sums up all Chekhov’s ideology.

Maybe it’s just me but I tend to prefer authors whose general principles and lifestyle are somehow close to mine. In this paradigm, Chekhov seems almost perfect. On the one hand, he enjoyed life to its fullest, sometimes in irresponsible ways (he wrote once: “while in St. Petersburg, I drank so much that Russia must be proud of me!”).

On the other hand, he was a devoted worker who combined literature with medicine, which was his profession (“medicine is my lawful wife, while literature is my mistress,” he said), and he spared no effort helping everyone around, from his parents, siblings and numerous friends, to local peasants whom he treated free of charge. In 1890, he went to the remote island of Sakhalin (6,400 km east of Moscow), where he helped to conduct a census, writing a non-fiction book on the inhumane treatment of prisoners sent to Sakhalin.

He died young, at 44-years-old, of tuberculosis, which he had been suffering from since his 20s. While he knew that he was doomed, he behaved with dignity and humor until his dying breath. Thus, he sets a perfect example of a person who doesn’t complain and whine. What can be more useful in this day and age?

Anton Chekhov with his wife Olga Knipper, an actress who starred in his several plays.

Public domainLast but not least – internationally, Chekhov is most well-known for his theatrical legacy, and is one of the most frequently staged playwrights along with William Shakespeare and Henrik Ibsen. His masterpieces such as The Seagull, The Cherry Orchard and Three Sisters never age as they have the unlimited depth of subtext, and are always open for interpretation.

Konstantin Stanislavski, a famous Russian stage director who worked with Chekhov, said: “Chekhov often expressed his thoughts not in speeches but in pauses or between... the characters often feel and think things not expressed in the lines they speak.” True – and to my mind, leaving something to the subtext is way better than shouting it in readers’ or audiences’ ears.

A light of hope always shines through all this subtext and words unsaid, all the tiredness and imperfection of Chekhov’s heroes. One of his plays, Uncle Vanya, finishes: “We shall find peace. We shall hear the angels; we shall see the sky sparkling with diamonds.”

This subtle and light hope for something better, supplemented with humor and healthy cynicism, runs through all of Chekhov’s works, which, in my opinion, makes him the best Russian writer. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky couldn’t do better, with all due respect.

To read an alternative opinion on who's best in Russian literature, read our ultimate list of 112 writers composed by Russia Beyond's literature editor.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox