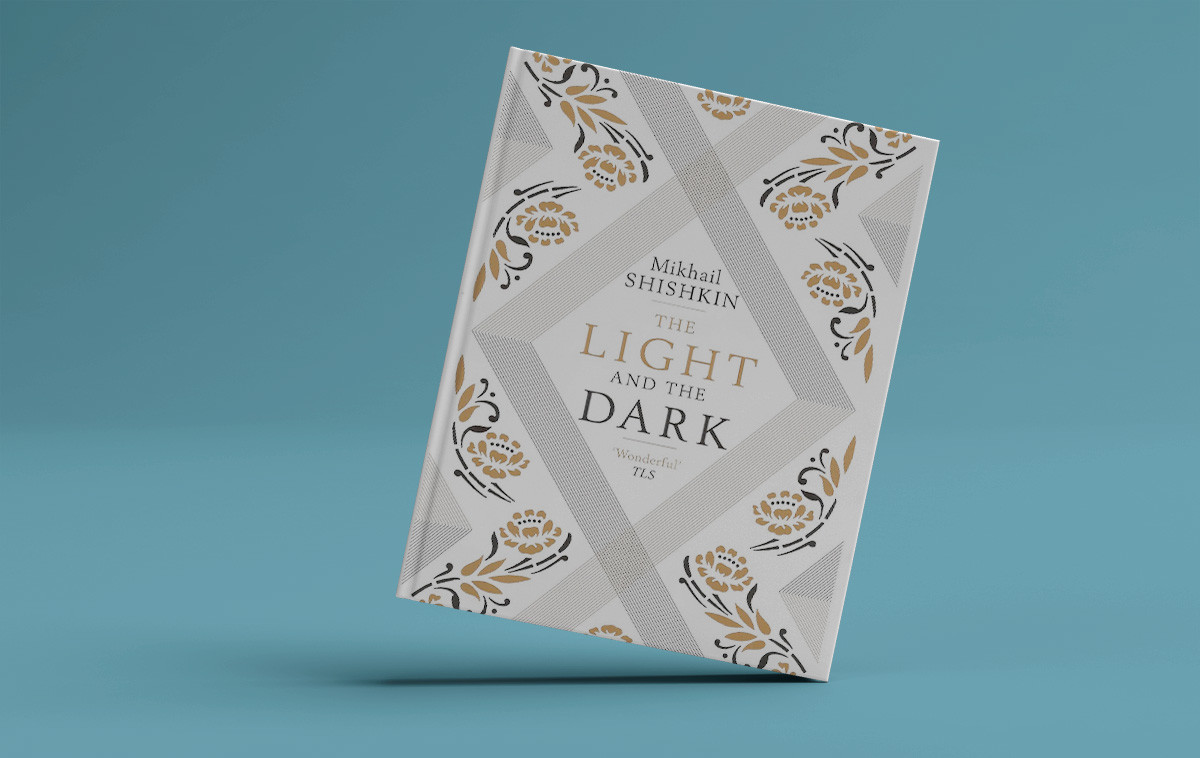

The novel takes the form of correspondence between two lovers. However, time and space here do not coincide. He writes from a distant war, the Battle of Beijing in 1900, while her replies come throughout the course of the 20th century. Most likely, he is no longer alive. The author hints to the reader that time, distance, and even death are no barrier to true love.

A scene from Marina Brusnikina's production based on Mikhail Shishkin's Letter-Book (Pismovnik) novel (The Light and the Dark in English translation), performed at the Chekhov Moscow Art Theater

Alexander Kurov/TASSThe novel was effectively a ready-made drama, and several theaters staged it. Shishkin, who lives in Switzerland, is well-known in the West, including for his earlier work Maidenhair. As such, The Light and the Dark was immediately translated into several languages.

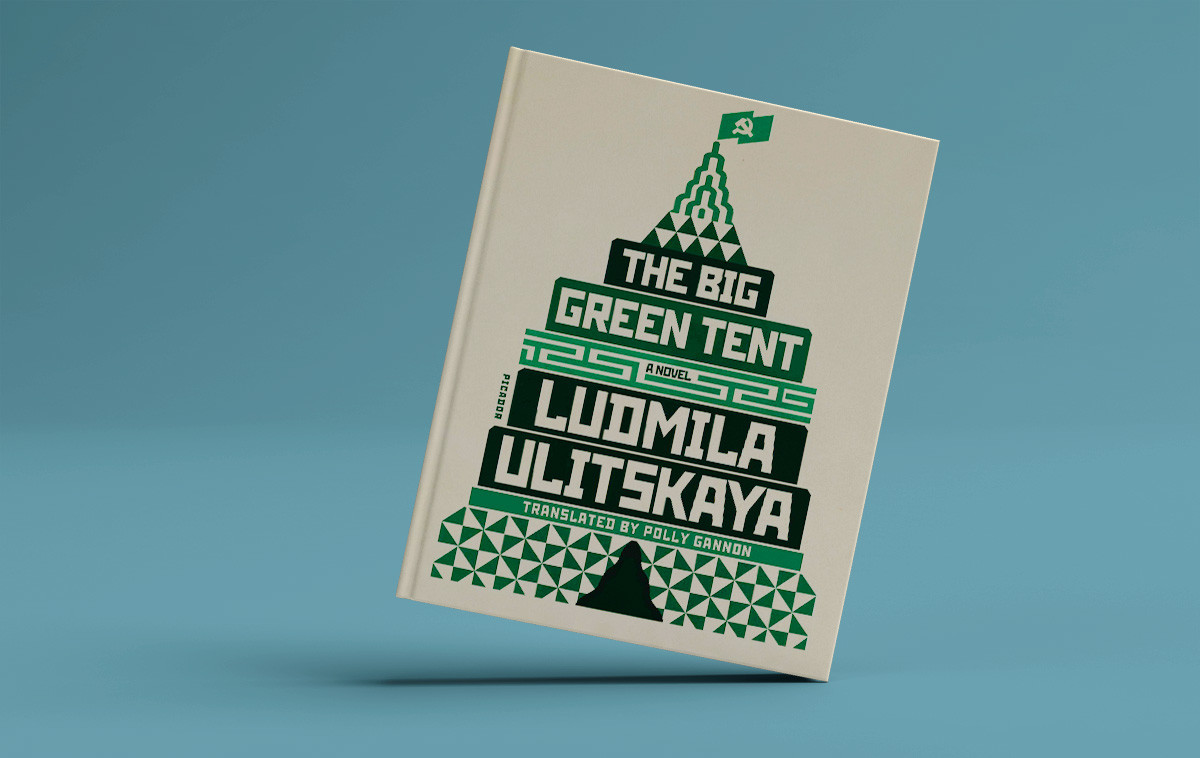

This book about samizdat and life in the USSR in the 1960s and 70s contains a feast of characters, each with their own destiny. Someone is forced to denounce their friends, another is fired from work and unable to find employment elsewhere, and a third has to renounce their own parents because they fall short of the ideals of the Communist Party.

Ulitskaya offers an in-depth cross-section of society at that time, when after the brief “Khrushchev thaw” the USSR again stumbled into the abyss of totalitarianism, and the fate of every person could be broken at the whim of the KGB.

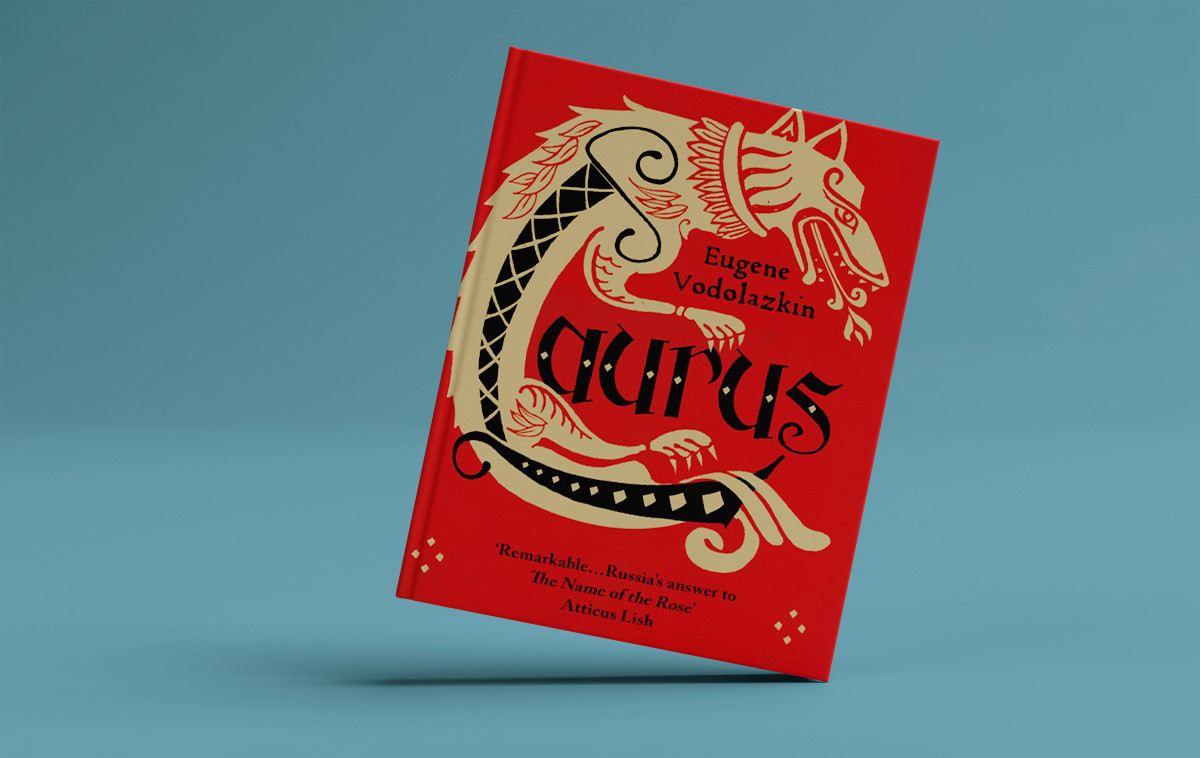

Medieval Russia. The bride-to-be of the young Arseny dies during a difficult childbirth. He believes that the blame rests on his shoulders, since they were not married. So he decides to devote himself to a life of prayer for the salvation of his fiancée’s soul. Taking the new name Laurus, Arseny becomes a wanderer and makes a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, before finally settling down as a hermit monk in the forest, where he receives and heals the sick.

Vodolazkin was the first in modern literature to address the theme of holy fools, who feature prominently in the medieval history of Russia. Ever seen St. Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square? It just so happens to be named after one of them. These “people of God,” as they were called, could be excused all kinds of misdemeanors, even insolence when addressing the tsar.

After the release of the book, Vodolazkin, a philologist and specialist in medieval Russia, was dubbed the “Russian Umberto Eco.” But despite the obvious influence of the latter, Laurus is strikingly original and imbued with a deft stylization of Old Russian speech (a real headache for translators) and profound reflections on moral values.

Lazarus Lindt, a Jewish mathematical genius, is strangely undisturbed by the revolution, the Russian Civil War, the Stalinist purges, and the even Second World War. Instead, the author tells his story through the prism of those he loved. At first it was Marusya, the wife of his boss, who considered Lazarus to be her child and was 20 years older. Then his own wife Galina, in whom the protagonist clearly sees the features of Marusya. Lastly, he serves as a mythical figure to his granddaughter Lidochka, whom he never got the chance to meet.

This unconventional family saga spans the entire 20th century, and masterfully shows how the lives of ordinary people were influenced by the political upheavals in the country, forcing them to adapt to new conditions of life.

Sorokin violates the usual linear form of the novel. Telluria, consisting of 50 virtually unconnected chapters, is an anti-utopia in which the author imagines Russia and Europe in the mid-21st century. In his mind’s eye, we see a new Middle Ages in which war has divided the territories into small principalities, home to not only people, but also mythical creatures, such as centaurs and cynocephali (dog-heads).

In the book, the metal tellurium becomes a kind of holy grail, a drug that allows the taker to comprehend everything they wish and embark on any spiritual path. But as well as opening up unheard-of possibilities, it is also deadly...

Sorokin is one of Russia’s most controversial modern writers, who takes pride in shocking readers with his conceptual novels. He launches thinly veiled attacks on the government, and often riles Kremlin supporters and the Russian Orthodox Church. His books have been the subject of court cases and even ritual burnings. All the same, he remains one of the country’s most widely read authors.

Before the publication of this monumental work, Prilepin was known as the author of biographical tales and short novels about Russia’s riot police, the war in Chechnya, nightclub bouncers, and everyday problems faced by young guys from the provinces.

In The Abode, his simple, grassroots characters are inmates at the Solovki prison camp at the dawn of the Soviet Gulag in the 1920s. The writer meticulously trawled through documentary sources to create vivid real-life portraits of the ambiguous camp leader, the prisoners, and their paradoxical existence inside monastic-turned-prison cells with dreams about freedom.

This is not just another novel about the horrors of the Gulag, but the story of a simple guy trying to survive in wretched circumstances, all the while wrestling with his conscience.

The Muslim woman Zuleikha, from a Tatar village, lives under the oppression of an authoritarian husband and mother-in-law. The Soviet government too recalibrates her life — dispossesses her family (accused of being kulaks or rich peasants), kills her husband, confiscates her farmland, and sends her to Siberia. In a bizarre way, it is there in exile that she discovers herself as a person, and begins to feel, rather than mechanically doing what she is told.

Actress Chulpan Khamatova on set of Yegor Anashkin's film 'Zuleikha Opens Her Eyes' based on Guzel Yakhina's novel

Yegor Aleyev/TASSThe debut of Guzeli Yakhina, a writer from Kazan, was the literary event of the year and became a bestseller. In penning the book, she drew extensively on the stories and recollections of her grandmother (who, like Zuleikha, spent years in Siberian exile) and other Tatars dispossessed in the 1920s.

A group of Afghan war veterans-turned-gangsters keep an entire small provincial town in fear. Locals bow down before them, asking to be allowed to trade or begging not to be punished. On one occasion, they illegally seize a new real estate development for themselves and their families to live in.

The main character, Herman, is different from his “colleagues” in the gang. He dreams of a quiet life in sunny India, while memories of Afghanistan cause him to shudder. What’s more, he is forced to hide his feelings for the ringleader’s girlfriend...

A still from 'Bad Weather' TV series

Sergei Ursulyak/Moskino 2018This book was one of the best artistic interpretations of the “wild nineties” in Russia. Ivanov succeeded not only in portraying the atmosphere of life in a provincial town, but in spotlighting the new classes of post-Soviet people and their values.

The Petrov family gets sick one by one. Thereafter, the entire work proceeds through the prism of their feverish consciousness, in which the boundaries between reality and their flu-induced hallucinations become blurred.

Salnikov’s main accomplishment is to create a wholly new style of writing that paints the tiniest details of everyday life, be it a drop of perspiration on a sick person’s forehead or the twitching of a leg under a blanket.

Petrovy theater performance by Kirill Serebrennikov

Gogol CenterThe author became an overnight literary sensation and the discovery of the year. He picked up several awards, and the renowned director Kirill Serebrennikov is shooting a movie version.

This is a first-“person” narration of the life of a Moscow cat from cradle to grave. It is as if the author attached a GoPro camera to a stray animal and penetrated the very thickets of its mind. Along the way, the reader is taken on a fascinating journey through Moscow’s less glitzy haunts.

At first, Sluzhitel’s literary debut raised a few skeptical eyebrows among readers and critics alike — somehow the cat’s-eye-view technique seemed unoriginal, and there were fears of clumsy metaphors and awkward attempts to impose a feline worldview. However, such misgivings proved unfounded — the book won a people’s choice award and forced its human readership to look afresh at everyday things around.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox