Julian Henry Lowenfeld on the honorary ceremony of granting the Russian citizenship

Yevgeny Biyatov/SputnikAmerican poet, composer, playwright, and lawyer Julian Henry Lowenfeld spends half of his year in Russia: traveling around with lectures, book presentations and dramatic performances. He is a strong admirer of the U.S. and Russia, and he combines his love for both countries through his passion for Alexander Pushkin and by trying to educate American audiences about the great Russian poet. Moreover, he writes his own plays in Russian and they are performed here.

Precisely due to his efforts to bring Pushkin to the English-speaking world, as well as his overall promotion of Russian culture, Julian was recently granted Russian citizenship, making him one of the very few native-born Americans who became Russian, even though they don’t have a drop of Russian blood.

Julian’s great grandfather, Raphael Löwenfeld, was a translator of Leo Tolstoy into German, and he wrote the great author’s first-ever biography, Conversations about Tolstoy with Tolstoy. He also staged Tolstoy’s plays and founded the Schiller Theater in Berlin - the only theater for the masses and not the elite. After the Russian Revolution, the Nabokov family found shelter in the Löwenfeld family home in Berlin.

None of this, however, automatically meant that Julian would grow to have a love for Russia. In fact, quite the opposite was highly likely. “I grew up during the Cold War fearing Russia, and indeed, my history tutor at Harvard was Richard Pipes, a senior member of President Reagan's National Security Council. If all I had ever known about Russia had to do with geopolitics, then everything would have predicted that I would have shared the natural antipathy of that time for ‘the evil empire’,” Julian says.

By the time Julian was a second-year student at Harvard, he’d never met a Russian or heard Russian spoken. But then he chanced to hear a bard playing guitar and singing a song that just melted his heart. It happened to be Bulat Okudzhava's 'The Prayer of François Villon'.

So, Julian decided to learn Russian. It took a lot of work, but he found the language to be so musical and expressive.

“There are so many emotional shades of the meaning of words in Russian, so many emotional colors possible. Take the word ‘brother’ - in Russian it can be brat, or bratok, or bratishka, or bratukha - and these all change the context and the emotional relationship. It’s a phenomenally rich and poetic language with so many different ways to say the same - or not quite the same - thing,” he says.

Julian’s Russian teacher loved Pushkin, so the first thing he read in the original was his poem 'I loved you once...'. And since Julian couldn’t find a translation with which he was entirely satisfied, he decided to translate it himself.

I loved you once, and still, perhaps, love’s yearning

Within my soul has not quite burned away.

But may it nevermore you be concerning;

I would not wish you sad in any way.

My love for you was wordless, hopeless cruelly,

Wracked now in shyness, now in jealousy,

Yet I loved you so tenderly, so truly,

As God grant by another you may be.

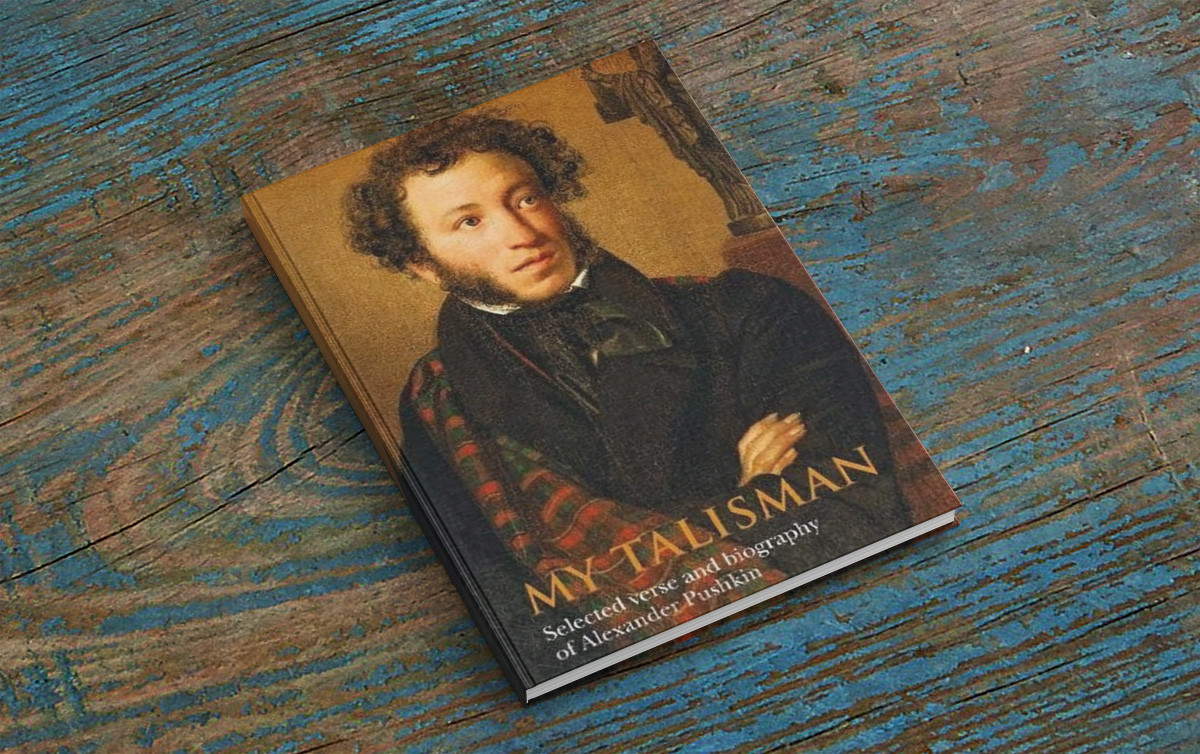

In December 2019, Julian’s book, My Talisman: Selected Verse and a Biography of Alexander Pushkin, was published (by Elegy Books). There are two editions, a bilingual one and a purely English one. The author says he insisted on publishing the bilingual version while publishers warned that it would be less popular. But Julian wanted his book to be a bridge between generations of emigrants, where, for example, the grandmother doesn’t speak English and the grandchildren already don't speak Russian. Of course, at the same time, for scholars it’s a great resource to have for scholars who want to compare the two texts mirroring each other side by side on opposite pages of in the same book.

“Marina Tsvetaeva wrote a letter to Paul Valéry: ‘They tell me Pushkin is untranslatable, but how he can be untranslatable when he is already a translation of the inexpressible and ineffable into ordinary speech? Ah, but to translate such a poet, you must be a poet yourself’ And I would add, being a poet myself, that the opposite of what Tsvetaeva wrote is also true. Because, in fact, poetry is indeed already translation out of ordinary speech into something ineffable and inexpressible. It’s a very curious art: you’re trying to say in words that which is already beyond words,” Julian says.

In show business, ratings have come to matter more than the Truth, and the wine of poetry degrades into a kind of saccharine tackiness and banality, a kind of spiritual Coca-Cola. “And Pushkin saves me from this every day with his irony and his tenderness, and his sublime way of simultaneously expressing both sarcasm and reverence, both indignation and eternal goodness and love,” Julian says. “Pushkin is a spiritual antidote to the vulgarity that besieges us daily. He is all about love and freedom, and indeed, about achieving happiness through living honestly. What could possibly be more important?”

Russian scholars admit that Julian achieved the impossible: he managed to keep the music, rhythms, rhymes of Pushkin's poetry, which no one could do before.

“The amazing depth, clarity, sparkling intelligence, wit and warmth of Pushkin’s verse are faithfully preserved in [Julian] Lowenfeld’s brilliant translations,” says Vsevolod Bagno, director of Pushkin House (Institute of Russian Literature) in St. Petersburg.

Julian says that the real way to translate a text is that you have to become the person you're translating at that moment. One needs to feel the poet and imagine how he felt when he wrote, and how he would say it in English.

To recognize Pushkin more deeply, Julian was looking for a good biography in both English and Russian, but he couldn’t find one. Some were written for scholars and didn't convey the poet’s wit, spirit and character. Others had some absurd political or neo-Freudian theories about his love life and or about his death. So, Julian decided to write his own biography, based almost exclusively on primary sources.

He spent several years working in archives in St. Petersburg, Pushkin Hills and Boldino - places where Pushkin lived and wrote. He studied remarkably vivid letters and reminiscences, plus the memoirs and letters of the poet’s friends and contemporaries.

Boldino

Dmitry MozzhukhinThus, his biography is based on first-hand research, not on other scholarly findings. He describes the life of the poet as it was in reality - a turbulent drama of love and passion, a bold quest for freedom and beauty in both his art and his life. This work has not only changed Julian's understanding of Pushkin, but also changed his life entirely - in Boldino he met his future wife, a journalist who interviewed him at the museum.

While America's main value is claimed to be freedom, Russia has another type of freedom, something different from what Americans might perceive. This is not the freedom to march in front of the White House (which is also great), but rather, it’s an inner freedom to be spontaneous, not to have everything prearranged, to visit suddenly your friends without making an appointment in advance, to enjoy life in any circumstances. This is what Pushkin's poems give a sense of.

“When I was an exchange student in Russia, it wasn't just that you would go visit friends with an intensity beyond anything I had ever experienced back home. It was that our conversations would never end, and even when I left their kitchen, my friends would even ride the tram with me to the Metro just to be sure I got where I needed to go. That intensity of caring and devotion would just never happen in friendships in America when I was growing up.”

Eventually, Julian’s father advised him that he should get a “real job”, leaving poetry and translation as a hobby. So, Julian became a lawyer and an expert in Russian copyright law, defending Russian film studios. After one high-profile case the media even said that Julian was ‘Cheburashka’s lawyer’, which is in reference to a character from a popular Soviet book and animated film whose iconic image had been pirated.

“Russia made me more compassionate, more passionate, gave me a stronger sense of humor, less expecting that everything goes as planned, and more open to slings and errors. I think it was Woody Allen who said: 'If you want to make God laugh, tell Him about your plans;' well, Russia is certainly that way. It forces you to become more spontaneous, more vigilant, yet at the same time more trusting. I had always been atheistically-ironically inclined, but when I came to Russia I actually begin to believe in God. And in Russia I found love. So I am eternally grateful to Russia,” Julian says.

While Russians consider Pushkin as their leading poet, Western nations are more familiar with those ‘two multi-volumed guys’.

“I don’t want to diminish the genius of either Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, but in a way they are very convenient geniuses through which to cling to the established Western perception of Russia as someplace hopeless, gloomy, heavy, difficult, and perpetually full of suffering, pain, cold and darkness,” Julian says.

“I think no one will ever truly understand Russia unless they read Pushkin, because Pushkin is much closer to the Russia I know and love. And he certainly is by far the most accessible in his values of all the great Russian writers, practically American in his love of freedom and his sunny optimism and light-heartedness. To those who believe Russian literature is only about suffering, the fact is that the greatest of all Russian writers, Pushkin wrote: ‘They say happiness is a good school. Perhaps - but happiness is the best university. It completes the upbringing of a soul capable of virtue and beauty.’”

L-R: Portrait of Leo Tolstoy by Ilya Repin, portrait of Alexander Pushkin by Orest Kiprensky, portrait of Fyodor Dostoyevsky by Vasily Perov

State Tretyakov Gallery, Public domainMoreover, Julian says Hollywood should study how to make happy endings just like Pushkin did. He was one of the few Russian authors who could write a really satisfying happy ending (The Captain’s Daughter, The Blizzard), which could yet prove utterly surprising and wouldn’t be predictable or banal to the reader. “Pushkin’s plots keep you in tension the whole time, while sparing you a 30 page lecture about agrarian politics of Russia in the 19th century. And it’s real tension, where literally anything could happen, not the kind of fake tension we get for example, with James Bond, who we know will always triumph, because his whole brand depends upon it.”

In the future, Julian plans to erect a monument to Pushkin in London that will have the caption: “There is no Truth where there is no love.” Julian notes that for Pushkin love is the most important thing in life. Love rises above all political tensions and the individual ‘truths’ that we all each have. In the end, Love will lead us to the loftiest and most irrefutable higher Truth.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox