Wedding scene from The Pokrovsky Gate, 1982

Mikhail Kazakov, Mosfilm, 1982Because the Soviet Union was an atheist state, most of the centuries-old Russian marriage rituals were mixed, if not replaced, with newly-made Soviet secular traditions. Starting from the 1960s, wedding celebration traditions were consolidated into a set of rituals most families would want to follow. A typical Soviet wedding day, for instance, would start with the groom and his civil “witness” (свидетель) picking up the bride from her home in a decorated taxi or a private car.

Sometimes the couple’s relatives and friends would decorate the couple’s car in a more extravagant way, putting a doll in a wedding dress (usually the doll belonged to the bride as a girl) on the car hood.

Andrey, the witness from the photo below, says that as soon as the bride’s family, neighbors, or any passersby caught sight of the decorated car, they would form all kinds of obstacles to not let the groom approach the bride. To get rid of such hindrances, the groom would have to pay a “ransom” for the bride by giving out bottles of champagne or singing songs to everyone who stopped him.

After the Communist Revolution, the Church had ceased to preside over peoples’ marriages. Instead, a new institution called the ZAGS (ЗАГС) - the department of public services - had appeared with the purpose of registering new families. The process of becoming a husband and wife became quick and formal. Two witnesses (basically the equivalent of a best man and a maid of honor) were a new requirement at every marriage registration. The civil witnesses, or свидетели, would sign papers, together with the husband and wife, confirming the act of marriage.

Andrey remembers that being a witness was a privilege - свидетели were treated as the main couple of honor after the bride and groom at the wedding. At most weddings, they would have to wear red ribbons across their chests to showcase the importance of their role.

As always, the presence of communist-socialist ideology permeated everyday lives. In almost every Soviet ZAGS, young couples and their guests would encounter a Lenin bust - at the very least his portrait.

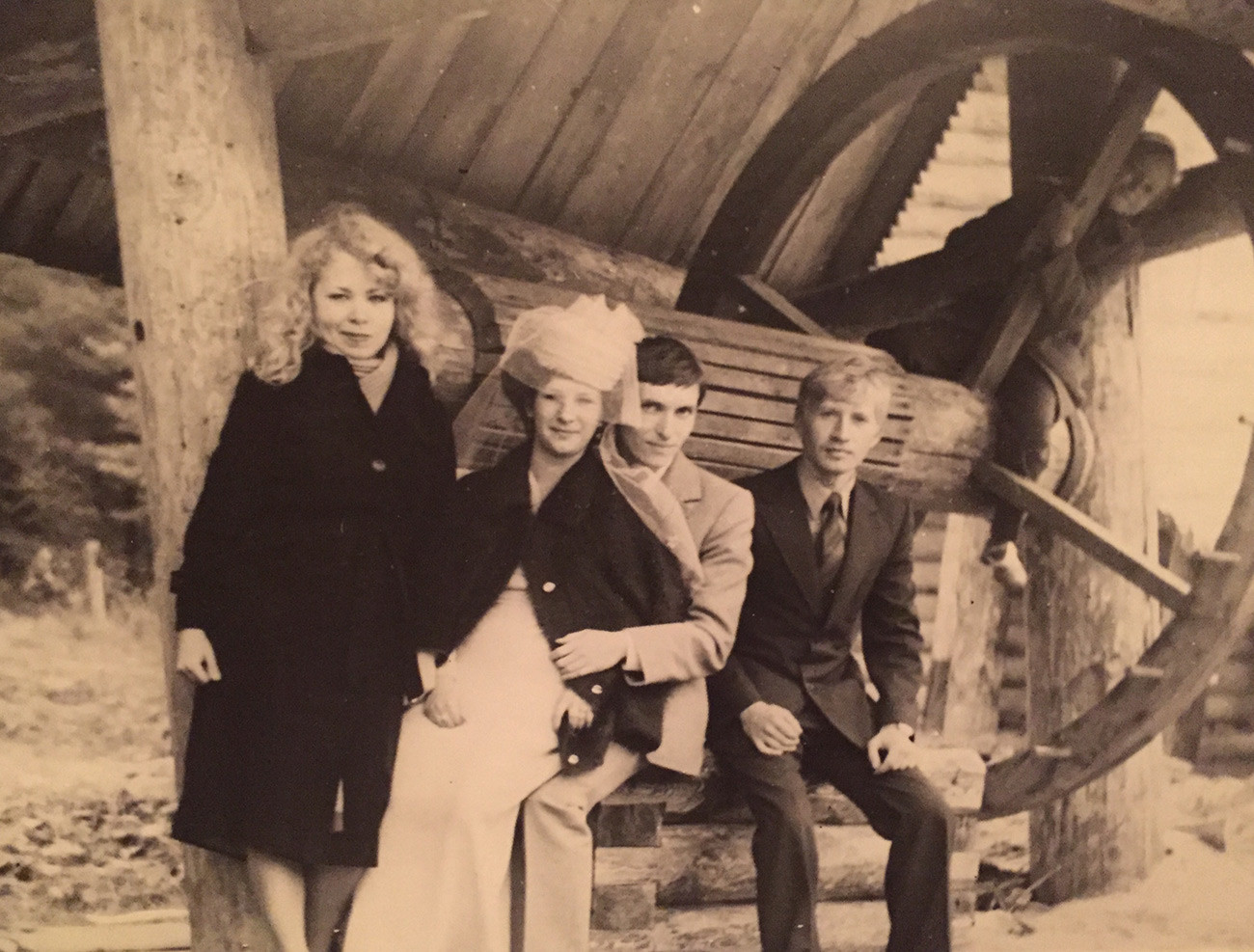

After registering at the ZAGS, the newlyweds and their witnesses would go to take photos by the city landmarks, for the family archives. Among the most popular landmarks in every Soviet city were the WW2 memorials, where people would go to place flowers.

A bride, groom, and their witnesses place flowers next to an “Eternal Fire” monument dedicated to Soviet warriors in the Second World War.

Vera, the witness (maid of honor) in the photo above, notes that, of course, it was not a requirement. However, many people simply felt that it was the right thing to do, because virtually every Russian family had had veterans or soldiers lost in the war.

If the wedding couple were to desire to continue the festivities after the registration and sightseeing, everyone would gather in a restaurant or the bride or groom’s apartment. Vera remembers that a man with an accordion was an almost ubiquitous sight at any Soviet wedding. Although the musician’s service was never cheap, it would always successfully entertain all the guests.

In the absence of an accordion player, people often chose to hold wedding parties in restaurants with a live band. The climactic wedding party scene from the film Kinfolk by Nikita Mikhalkov (1982) is a great example of this.

Irina, the bride from the photo below, remembers: “Among typical presents were all the necessary items for a young family, such as beddings, tea sets, alarm clocks, or plants. Most guests, however, would give money, because besides these gifts, there was not much else in shops. I remember, we spent almost all the gift money from my friends on the accordion man. Interestingly, my husband’s mother invited dozens of her colleagues, who we didn’t really know but who brought rare luxury dishes for the table, such as caviar, salmon, or cured meat.”

The most luxurious present, however, would often come from the Soviet state itself. Sometimes, when a couple of young prospective specialists married each other, they were pushed forward in line to get a room in a dormitory, a communal apartment, or even a private apartment.

The first wedding day would usually spill over into a second day of celebration among a smaller circle of friends and relatives. Then, after the second day expired, the newlyweds would either go on a honeymoon trip - thoughtfully organized and purchased by their parents - or return to their everyday work routine to continue striving for the welfare of the Soviet state.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox