Nowhere else have so many films about World War II been made as in Russia and the U.S. - we are talking hundreds here. Several dozen among them have become classics of world cinema. The two countries maintained a common interest in the topic during the Cold War years as well, but they rarely concurred on matters of subject matter, heroes or viewpoint. However, at times, history still forced their parallel narratives to intersect.

The importance of cinema as the most influential mass medium was not forgotten on both sides of the Atlantic, even during the difficult war years, and in fact, production never stopped. Movie making in the two Allied countries during those years was similar as far as genres were concerned - films were generally either uplifting dramas or comedies designed to boost fighting morale. But the heroes and stories differed greatly - they were dictated by the war itself. WWII engulfed almost the entire world, but in every hot spot it was different.

This Is the Army.

Michael Curtiz/Bert Glennon Sol Polito,1943In Hollywood, three themes dominated. Firstly, the military itself - i.e. soldiers in the theaters of war. Secondly, the home front and the lives of the families of those who had gone to war. And, finally, the people who found themselves between the front line and the home front - new conscripts getting ready to go to war. The biggest war-themed hit at the time was This Is the Army (1943), an adaptation of a Broadway production about an amateur army dramatics society. According to the plot, members of the troupe head off to their individual military units following their last show in Washington and none of them know whether they will ever get together again.

The “face” of Soviet wartime cinema was female. In the USSR until the first decisive victories, there were no movies set at the front. But there were a lot of films about the heroic struggle in areas occupied by the Germans and on the part of those who found themselves in captivity - for obvious reasons, nothing of the kind was made in the U.S., which fought on distant frontiers for the most part. What is important is that in many Soviet films - She Defends the Motherland, Rainbow, Zoya, Girl No. 217 and others - this struggle was waged by proud and strong women, serving as a vivid embodiment of the Motherland calling on people to come to their country’s defense (‘The Motherland Calls!’ was the name of a popular Soviet poster in the first year of the war).

The most important phase of WWII in the USSR was called the Great Patriotic War, which implied that everyone - men as well as women - was engaged in it. And so, too, were the movies.

During the four war years, about 70 feature films were released in the USSR and almost 50 of them were thematically linked to the war. For comparison, in the U.S., the war featured in fewer than a third of the total of over 1,200 movies produced between 1942-1945.

When the last shots died away, the ratio changed dramatically. There was a boom in movies about WWII in the U.S. in all sorts of genres - comedies, films noir and heroic action movies. The most successful film of the decade was The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), the William Wyler drama about three war veterans who return to “Civvy Street”, but fail to recover from their wartime experiences. The movie not only won seven Oscars (including best film), but also broke the box office record previously set by Gone With the Wind.

And in the USSR, it was a period of movie famine owing to ideological restrictions and the extremely dire economic situation. Just a few dozen films came out per year, and at the height of the crisis - in 1951 - only nine. A few of them touched on the war and even those could hardly be described as realistic. Genre movies such as the film noir Secret Agent, or Brave People, which echoed the conventions of an American Western, enjoyed great popularity with audiences.

The Fall of Berlin.

Mikheil Chiaureli /Mosfilm, 1949However, war epics glorifying Stalin as Supreme Commander-in-Chief were emblematic of the entire period. The complex and dramatic history of the Great Patriotic War was presented in terms of a series of victorious operations conducted under the personal command of the Great Leader. In Soviet historiography it was called ‘Stalin’s Ten Blows’. To consolidate this concept in the collective consciousness, it was decided to depict each “blow” in the language of cinema. In the end, only three of the 10 films were actually made, and the most famous of them was The Fall of Berlin by Mikheil Chiaureli. All the events in it were pure invention, including the finale, where a jubilant crowd greets Stalin in the vanquished enemy capital.

The history of cinema can be studied using the huge number of movies about WWII made on both sides of the Atlantic. But the distinctive feature of Soviet films is that watching them readily allows one to trace the history of the country. After Stalin died, Nikita Khrushchev came to power. He debunked the cult of personality and liberalized public and cultural life. ‘The Khrushchev Thaw’ arrived (almost exactly coinciding with the decade of the 1960s). Movies about the war changed, too. When the cinema industry came back to life, almost the first thing film directors did was turn to the subject of the Great Patriotic War. This included both directors who had fought in the war and those who were children during the war. For the first time since the war, they started depicting it not only as a great triumph, but also a great tragedy. Generals in the HQs and the front line almost disappeared from movies, as did the enemy - German presence was often reduced to a silhouette in the background. The focus moved to individual stories of ordinary Soviet people.

The Cranes Are Flying.

Mikhail Kalatozov/Mosfilm, 1957To a large extent, it is these new films about the war, imbued with humanism, that made Soviet cinema world famous. Just listing the awards speaks volumes. Mikhail Kalatozov's The Cranes Are Flying (1957) - a movie about the turmoils in the life of a young girl, whose boyfriend has volunteered for the front - won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, the only Soviet film to ever win the award. Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Tarkovsky's debut film about a boy morally crippled by war, earned the USSR a Golden Lion, the main prize of the Venice Film Festival. Grigory Chukhray’s Ballad of a Soldier (1959) about a young soldier who is granted leave and goes to visit his mother, was nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay. And, finally, somewhat later, The Ascent (1976) directed by Larisa Shepitko about two partisans captured by the Germans won a Golden Bear in Berlin.

If, in the USSR, the 1960s are remembered as the heyday of auteur cinema, in the U.S. that decade was a time of genre classics - suspense-filled war thrillers about hard-bitten tough guys. One after another, movies came out that audiences around the world still love and watch today, such as The Guns of Navarone (1961) with Gregory Peck and David Niven, or The Great Escape (1963) with Steve McQueen. The latter also featured Charles Bronson, who four years later starred in the celebrated movie The Dirty Dozen.

One movie released in the 1960s had a decisive impact on Soviet cinema. The Longest Day (1962), a three-hour long, large-scale reconstruction of the Allied landings in Normandy, enjoyed enormous success and sparked an appetite for epic war dramas. All these monumental movies made in the West had one thing in common - they almost completely ignored the Eastern Front. This led to much indignation on the part of the Soviet authorities and the Kremlin decided to respond by telling the story of who had really defeated Nazi Germany.

These were the circumstances that led to the making of Yuri Ozerov’s epic Liberation (1969-1971), which aspires to the status of a comprehensive chronicle of World War II. The action moves freely from the Supreme Commander-in-Chief’s HQ to Hitler’s bunker, and from a Soviet dug-out to Churchill’s war room. Ozerov was actually only allowed to start with the Soviet victory in the Battle of Kursk (1943), but the director subsequently shot the missing parts. The movie is symptomatic of the Brezhnev period of stagnation when military subjects migrated from auteur cinema to the mainstream.

The Dawns Are Quiet Here...

Stanislav Rostotsky/Gorky Central film Studio for children and youth films, 1972In the USSR in the 1970s, films about the Great Patriotic War were made copiously and frequently - both large-scale epics in the Ozerov mould and movies about “battles of local significance”. But the number of outstanding works was small, and hard-hitting and original ones were even fewer. Only a handful stood out from the crowd. One could single out the Oscar-nominated drama The Dawns Here are Quiet or the completely un-histrionic “Leningrad school” movies (Aleksey German's Trial on the Road and Twenty Days Without War, Semyon Aranovich's Torpedo Bombers, Viktor Aristov's Gunpowder).

After a brief resurgence during the period of perestroika in the 1980s, when it became possible to broach prohibited and semi-prohibited topics (such as the anti-retreat units, disciplinary battalions and collaborationism), the Great Patriotic War all but disappeared from Soviet cinema. Different armed conflicts began to preoccupy directors - namely Afghanistan and Chechnya.

Interest in WWII had petered out even earlier in Hollywood, where the war film genre was almost fully taken up with Vietnam. Only movies about the Holocaust were and still are regularly made. The most high profile of these was Steven Spielberg’s Schindler's List (1993). Five years later, he was to direct another movie that would effectively relaunch the war film genre. Saving Private Ryan will be remembered, above all, for its highly realistic scenes depicting the Normandy landings, which became a benchmark for all subsequent directors. Since then, however, few have managed to combine scale with genuine humanism to the same degree.

The Great Patriotic War only became a regular subject of movies again at the turn of the century. After a succession of experiments with genres - one could cite the spy thriller In August 1944 (2001) or the Western-genre-inspired Our Own (2004) - a return to the aesthetic of the heroic dramas of the Brezhnev era became the prevailing trend.

Stalingrad.

Fyodor Bondarchuk/Art Pictures Group, Non Stop Production, Rossiya-1, Columbia Pictures, Mosfilm, Fund of Kino, 2013The greatest success with audiences, however, is enjoyed by movies filmed at the interface between Western and Soviet traditions. One could mention the action dramas T-34 (2018), which portrayed a duel between two tank crews, and Stalingrad (2013), which showed the defence of an unvanquished building in the destroyed city. The latter was shot by Fyodor Bondarchuk, a student of Yuri Ozerov and the son of the Oscar-winning director Sergei Bondarchuk. Strange as it may seem, some Soviet influence is also felt in American war movies today. For instance, legendary cinematographer Roger Deakins, who has just won his second Oscar for his involvement in the World War I drama 1917, has spoken in homage to the Elem Klimov film Come and See (1985). And cinematographer for the recent movie Fury (2014), Roman Vasyanov, a Russian who has made a career in Hollywood, described it as a “Soviet film with Brad Pitt”. He admitted that the movie strongly reflects the influence of Russian directors such as Klimov and Aleksey German, whose work he and the director had analyzed in the run-up to filming.

Trial on the Road.

Alexey German/Lenfilm, 1971Cinema-goers only got to see Aleksey German’s film in 1985 after it was “shelved” for nearly 15 years. The censor’s objections were perfectly explicable. Given its gritty manner of execution, its unheroic heroes and its very plot, the movie was at odds with the “lofty” style of film-making on wartime subjects in literally every respect. A former collaborator, Lazarev (Vladimir Zamansky), joins a group of partisans, but no-one believes he has genuinely repented. And so it is decided to put him to the test - he is sent on a mission from which it is going to be almost impossible for him to come out alive.

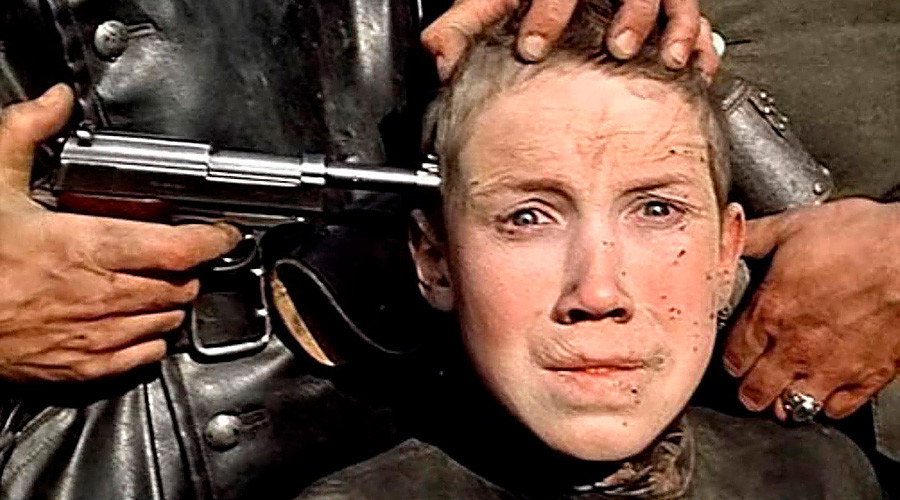

Come and See.

Elem Klimov/Mosfilm, Belarusfilm, 1985Elem Klimov’s dark masterpiece is still described as one of the most harrowing films in the history of world cinema. And, as a logical consequence of this, it is also seen as perhaps the number one anti-war film. Long preoccupied with ways of conveying borderline states of mind onto the screen, the director made a film about a boy who encounters absolute evil. A Belarusian teenager named Flyora (Aleksey Kravchenko) finds himself at the epicenter of a Nazi punitive operation, in which dozens of civilians are burnt alive in a wooden barn. The screenplay was based on the story of the Katyn tragedy.

The Cuckoo.

Alexander Rogozhkin/STV, 2002Director Alexandr Rogozhkin made his name directing popular comedies, and then, out of the blue, he came up with The Cuckoo, a movie pretty much unlike any other, not only in his own filmography, but in the whole of Russian cinema. With the war already approaching its end, a girl from the Sami ethnic minority takes in two soldiers from warring armies. The Russian is suffering from concussion and keeps trying to kill the other, a Finn. The Finn does not wish anyone any harm and only dreams of going home. And the Sami girl herself has long been living in the bosom of nature and wants nothing to do with wars. Everyone speaks only their own language and none of them know the languages of the others. But they are all human, and so end up reaching an understanding of each other.

Casablanca.

Michael Curtis/Warner Brothers, 1942There are no shots of rows of tanks, shell-torn dug-outs or martyr’s deaths in this movie. Almost the entire action takes place inside an upscale gaming club in the Moroccan city of Casablanca belonging to Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) - a blasé American who believes neither in high-sounding phrases nor noble ideals. The movie is actually supposed to be a romantic melodrama. But it is difficult to find a more inspiring movie about the sense of duty that dwells in the heart of every decent person - whatever he might think of himself. The film demonstrates that war sometimes brings out the best in people.

The Great Escape.

John Sturges/ United Artists Mirisch Company, 1963In the year of its release, critics accused the movie of frivolity and predictability, but with the passage of years, its shortcomings have easily turned into strengths. Today, The Great Escape is seen as a paean to resourcefulness and ingenuity. Even in captivity and under threat of death, the cheerful, fearless lads never lose heart, and after the latest setback, they will venture into the breach once more. The film was selected for the famous 1963 Moscow Film Festival and (naturally) lost to Federico Fellini's 8½. But it did not go completely unrewarded - Steve McQueen did get the best actor award.

Letters from Iwo Jima.

Clint Eastwood/Amblin Entertainment, DreamWorks SKG, Malpaso Productions , Warner Bros. Pictures, 2006At the age of 76, Clint Eastwood carried out what can, without exaggeration, be called a remarkable experiment. In a single year, and almost simultaneously, he directed two movies about the battle for the island of Iwo Jima - one of the most important U.S. battles of WWII. The first, Flags of Our Fathers, depicted events from the American point of view, and the second - Letters from Iwo Jima - the way the Japanese saw them. And, curiously, the second of the two companion films, fully (!) shot in Japanese, turned out to be more powerful. And the stereoscopic effects rendered the senseless brutality of war exceptionally vivid.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox