Great filmmakers have long flourished in Russia and the Soviet Union, creating singular works that continuously pushed the medium forward. Of that ilk, the most well-known directors outside of Russia are Tarkovsky, Eisenstein and Vertov. However, there are countless others that have played a pivotal role in shaping Russian film history and are deserving of your attention. Here are my top five lesser-known classics.

Simply put, Russian cinema didn’t begin with Eisenstein. Before the Russian Revolution, filmmakers were busy experimenting in documentary and artistic films. One director though, Władysław Starewicz, was in the process of kicking off Russia’s illustrious animation tradition.

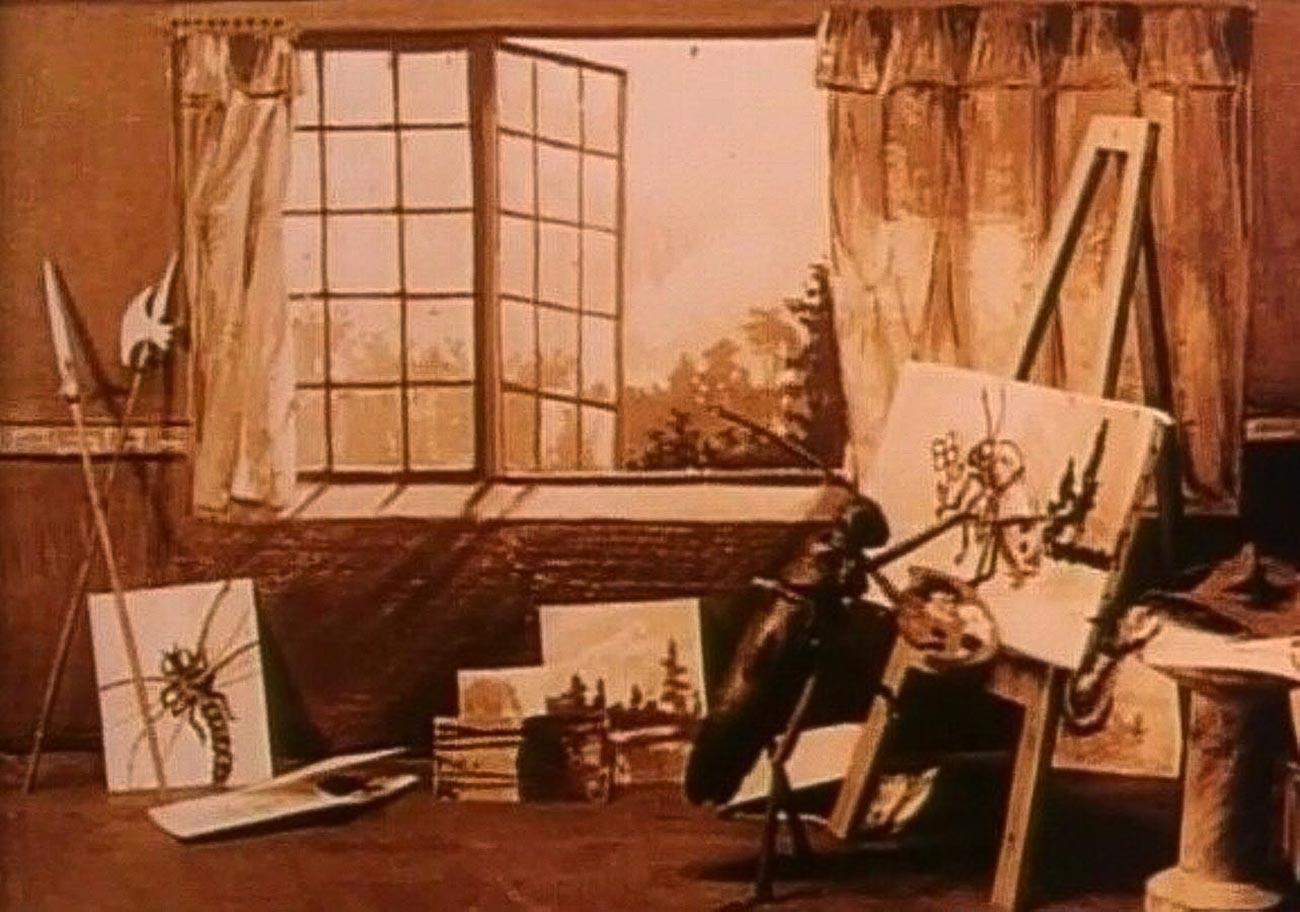

Starewicz pioneered a form of stop motion animation using preserved, dead insects. His most famous work, The Cameraman’s Revenge, starred bugs so realistic that audiences were convinced Starewicz had trained live ones. It proves that the way he anthropomorphized these bugs and gave them human features was completely ahead of its time. To see this, you only have to see how The Cameraman’s Revenge far surpasses the early animation work that Disney started a decade later.

The movie tells the story of the extramarital affairs of a couple, Mr. and Mrs. Beetle. After Mr. Beetle catches and then ‘graciously’ forgives Mrs. Beetle for a tryst with an artist, a jilted cameraman then shows footage of Mr. Beetle’s own affair to everyone at the local insect cinema. Clearly, the husband himself couldn’t keep to the high moral standards he expected of his wife.

The 1920s is unquestionably the most revered period in Russian film history. During this time, cinema was the high art of the revolution: politically explosive and highly intellectual. And the groundbreaking Russian innovations that were implemented influenced filmmaking around the world. Most notably, Russians developed the theory and technique of montage – the selecting, editing, and fitting together of separate sections of a film.

Another big Soviet innovation, led by director Yakov Protazanov’s Aelita, was the development of the sci-fi genre. Aelita was the first movie to depict space flight and an alien society. On top of that, its constructivist Martian sets and costumes, as well as its unique score, set the stage for what sort of aesthetics and music people around the world would come to expect from sci-fi.

In this classic, a Soviet engineer named Los dreams of building a spaceship to take him to Mars. In the meantime, he suspects that his wife is cheating on him and so kills her. Pursued by detectives, he escapes from town – in his spaceship. On Mars, Los falls in love with the Cleopatra-like Princess Aelita and organizes a Soviet-style uprising of the Martian underclass. However, the uprising reveals Aelita’s true, non-communist colors.

In the 1930s, a cultural revolution led to Socialist Realism taking over as the dominant mode for filmmaking in the USSR. Socialist Realism was officially sanctioned by the government and upheld that art should represent everyday life. The caveat was that life and the future had to be shown in a positive light: something to look forward to.

Under these strict guidelines, the quality of filmmaking suffered. Still, there were interesting movies from the period that achieved great acclaim. One such film is the most popular film of its time – Chapaev. This film’s cult status continues to this day, largely thanks to its snappy, quotable dialogue.

The character, Chapaev, is an illiterate man who makes for a brilliant Red Army commander during the Civil War. He dies a hero’s death on screen, cementing the reintroduction of the individual hero to Russian cinema. While in 1920s Soviet movies, like The Battleship Potemkin, the unnamed masses are the heroes, in Chapaev, we get to see a charismatic, brave individual take center stage.

After the death of Stalin in 1953, a new period in Soviet life began – The Thaw. This period, marked by Khrushchev’s premiership, led to an increased openness in cultural life. Previously banned works were released and, instead of Socialist Realism, filmmakers strove to convey believability. However, hopes that had been raised during The Thaw were gradually shattered once Khrushchev left power.

In the ensuing era of artistic clampdown, labeled ‘Stagnation’, comedies became the USSR’s most popular genre and a new avenue of subversion. The king of comedies during this time was the prolific director, Leonid Gaidai, and his most popular movie was The Diamond Arm. When a modest Soviet accountant named Semen goes on a tourist cruise to Istanbul, a comedy of errors begins when smugglers mistakenly wrap his arm with a fake cast full of diamonds. Soon, Semen is working with police to foil the smugglers, who try to reclaim their diamonds in a series of failed, slapstick scenarios.

The thing is, Semen is a completely fear ridden character, incapable of acting out of his own free will. Even his trip abroad only happened because his wife forced him to go. We only see Semen break free with the help of alcohol. Drunk at an upscale restaurant, Semen takes over the band area and performs an absurd number called ‘A Song About Hares’. In the song, cowardly hares, who live in a dangerous forest, come out at night to sing about how they couldn’t care less and will “become brave as a courageous lion”. In singing this, Semen was essentially calling out to Soviet moviegoers to be indifferent to authority and become who they are meant to be.

Commissar was a 1967 movie so beset by censorship problems that it did not see the light of day until 1986, under the order of Gorbachev. Because of this, it is sadly the first and only film by its director, Aleksandr Askoldov. The primary problem authorities had with Commissar was its unheroic depiction of the Bolshevik cause in the Civil War.

The movie’s lead, Vavilova, is a ruthless female commissar serving in the Red Army during the Civil War. Her military career is put on pause, however, when she becomes inconveniently pregnant. During her pregnancy, she stays with a kind and loving Jewish family, the Magazaniks. However, there is trouble afoot. It’s clear the Magazanik children are being affected by the violent world that surrounds them. The day Vavilova arrives, they’re busy acting out a pogrom with dolls.

But the Magazanik children aren’t the only victims. Due to her ideological zeal, Vavilova herself abandons her newborn baby to go rejoin her unit. All this, the movie clearly says, is a waste. As a memorable scene shows, it’s akin to harvesting the desert with scythes. And so, Commissar calls into question the classic Soviet hero myth of the Civil War – Chapaev and others be damned.

Richard Wess is the creator of Russian Film Hub, a website, where you can legally watch hundreds of Russian movies with English subtitles for free. Richard spends a lot of time watching and thinking about Russian movies. He also loves exploring Russian culture in general. Read more about his project.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox