The Hermitage Museum during the war

Getty ImagesShortly after the German invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941, in just 10 days the staff of the Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow packed most of the more valuable items in their collections and spirited them away from the capital. But not without some significant difficulties on the way.

The unpacking of Alexander Ivanov's “The Appearance of Christ Before the People” in 1944

Tretyakov GalleryFor example, Alexander Ivanov's legendary canvas, “The Appearance of Christ Before the People,” in the Tretyakov collection is so huge that it did not fit into any railway carriage. Director of the gallery, Alexander Zamoshkin, himself measured the railway cars, trying to figure out with railway workers what could be done. In the end, the 5.5 x 7.5 meter painting was rolled up, wrapped in tarpaulin and transported on two open railway cars.

Ilya Repin's "Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan"

Tretyakov GalleryA Tretyakov Gallery employee, Sofia Goldstein, later recalled how they were carrying boxes and canvases from the gallery to the station, helped by very young students from vocational schools and Red Army soldiers.

One night in mid-July, a special train consisting of 17 cars secretly departed from Moscow to Novosibirsk (3,300 km from the capital). There, exhibits from the Tretyakov Gallery, the Pushkin Museum and several other Moscow museums were placed in the unfinished building of the Opera House. Part of the Pushkin Museum collection was also taken to the city of Solikamsk in the Perm Territory (1,500 km from Moscow).

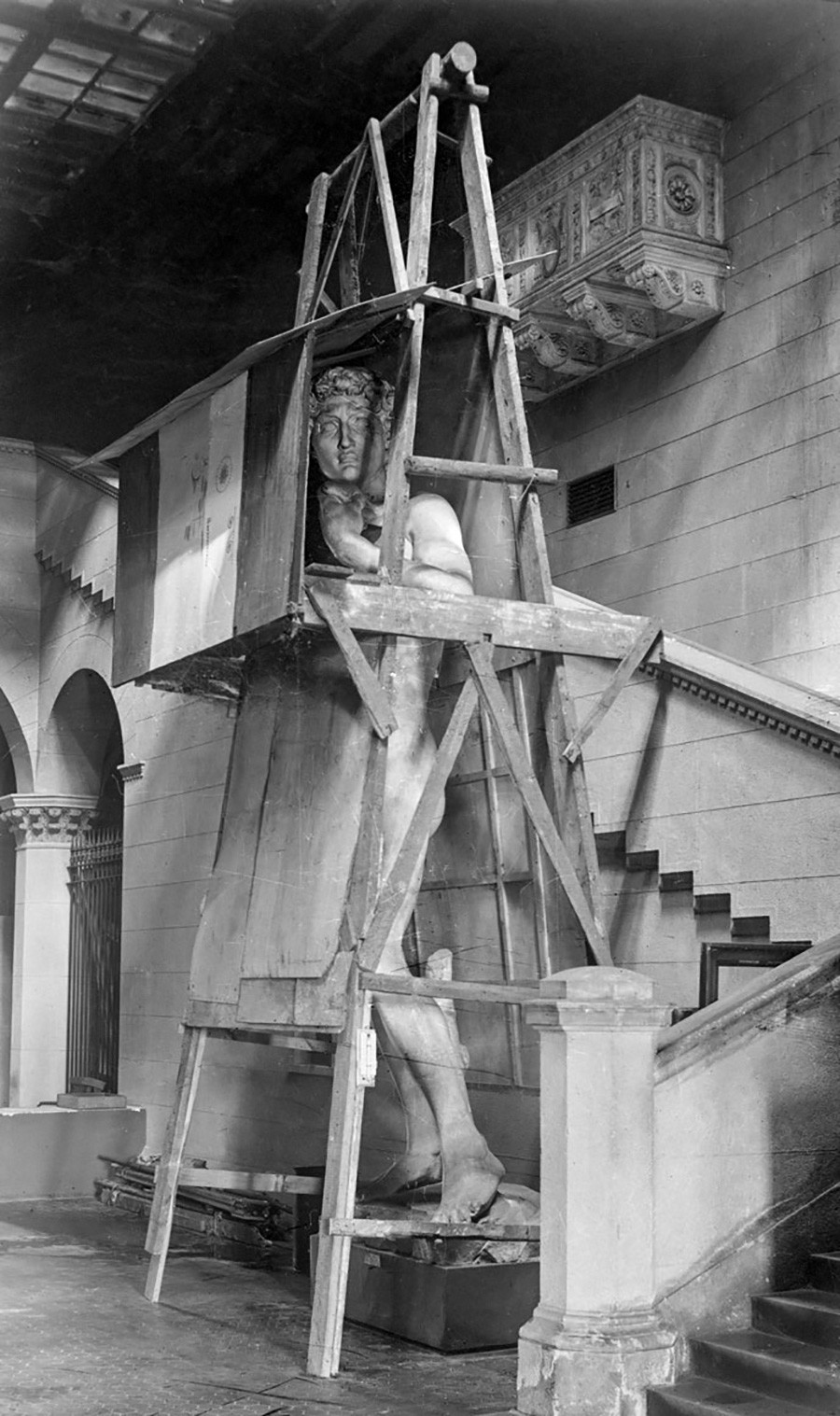

A copy of Michelangelo's "David" in a safety cage

Pushkin Museum of Fine ArtsThe process of evacuating exhibits from Moscow museums lasted for another year. In 1942, the building of the Tretyakov Gallery was damaged in an air raid: eyewitnesses recalled how snow and wind were blowing through its empty halls. Many museum employees were evacuated or went to the front, but there were also those who stayed behind, looking after the frames and waiting for the return of the collections.

The building of the Pushkin Museum also suffered: in October 1941, a blast wave destroyed its huge glass roof and shattered some of the windows. In addition to damage to the interiors of several halls, the famous full-size casts of sculptures in the museum collection, which could not be removed, were also scarred.

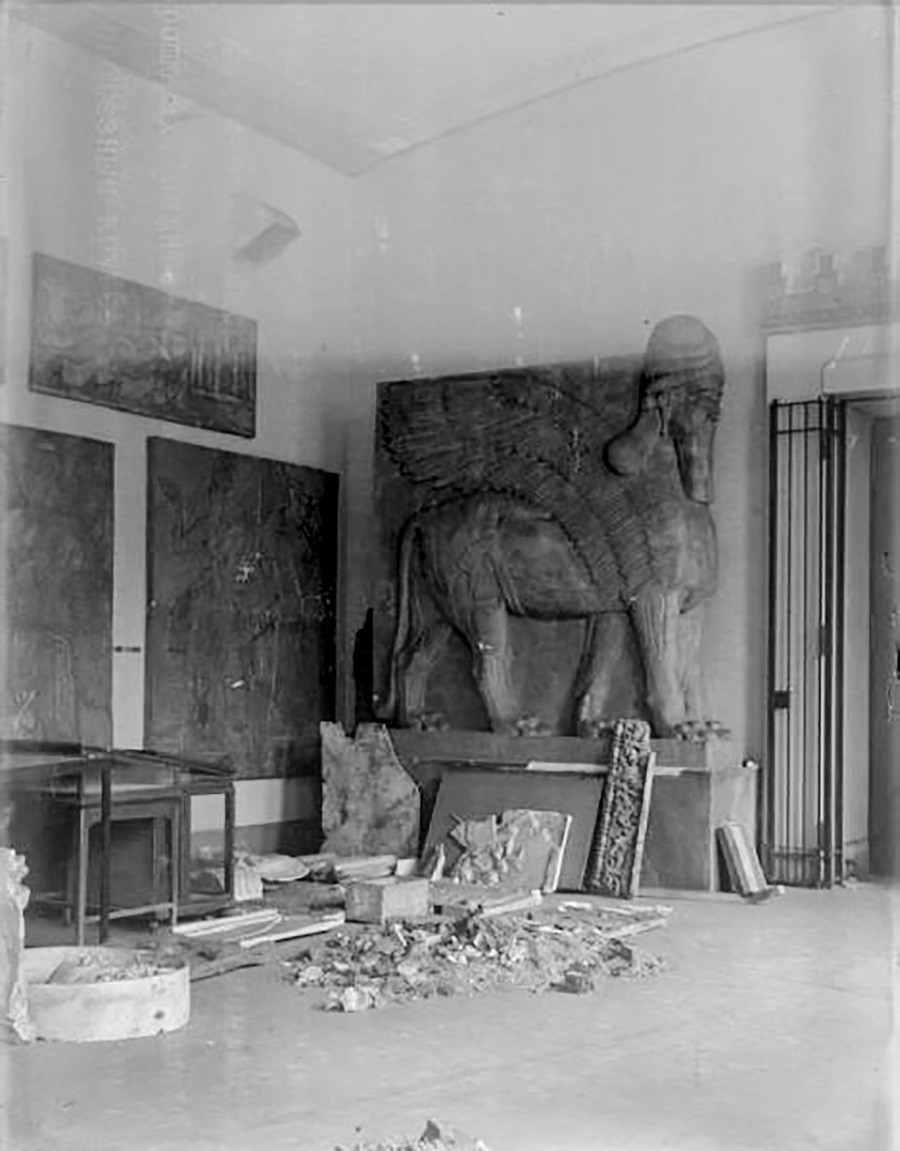

Pushkin Museum's hall for the Near East art

Pushkin Museum of Fine ArtsThe Tretyakov Gallery reopened just a week after Germany's surrender; the Pushkin Museum resumed work in October 1946.

READ MORE: 10 must-see masterpieces in the Tretyakov Gallery AND 5 fantastic reasons to visit the Pushkin Museum

The Historical Museum in Red Square, just like the Kremlin, could easily be targeted by enemy bombing. That’s why its various exhibits, from the sword of military leader Alexander Suvorov and poet Alexander Pushkin's golden inkstand to Ivan the Terrible's cloak and Catherine the Great's ceremonial dress, had to be evacuated as quickly as possible.

The task of dispatching the valuable cargo was overseen by archaeologist Alexander Bryusov. In late July 1941, over 900 boxes of treasures were transported on an open barge along the Volga River to the small town of Khvalynsk (900 km from Moscow). However, soon the front line came too close; there was fighting in nearby Stalingrad, and the boxes were sent by rail to Kustanay (present-day Kazakhstan; 2,000 km from Moscow).

The Historical Museum's staff is happy to see their collection back

The Historical MuseumThe museum, however, remained open during the war years. Its staff had made copies of some of the most valuable exhibits so that visitors had something to look at.

The originals returned to the museum in 1944. There are photos capturing the moment when delighted museum staff welcomed them back.

The Historical Museum's staff is happy to see their collection back

The Historical MuseumAs for treasures from the Kremlin Museums next door, at first the plan was to hide them inside the Kremlin: in its towers and in the crypts of the cathedrals. However, the Germans were approaching very fast and the Kremlin commandant, Nikolay Spiridonov, decided to evacuate the treasures. Some 75 percent of exhibits from the Armory went to Sverdlovsk (present-day Yekaterinburg; 1,700 km from Moscow), where they were stored in the NKVD building. Only royal carriages remained at the Armory. Likewise, most of the icons remained in the Kremlin cathedrals. The Kremlin itself was practically "hidden" from German aviation: its golden domes were painted dark, the red stars were wrapped in dark cloth, and the Tsar Bell was covered with wooden planks (READ MORE: How the Russians made the Kremlin 'disappear' during WWII).

A downed German plane right next to the Historical Museum and Kremlin, 1941

Archive photoThe Kremlin Museums were reopened before the end of the war. In April 1945, the first visitors were soldiers of the Kremlin garrison who had helped evacuate exhibits and then restored them to their places.

READ MORE: 5 reasons to visit the Historical Museum on Red Square

Museums in Leningrad (present-day St. Petersburg) suffered a harsher fate. Staff and volunteers spent day and night in the halls of the Hermitage in order to pack as many exhibits as possible. The first echelons carrying the collection left pretty quickly: about a million valuable items were taken to Sverdlovsk in the Urals.

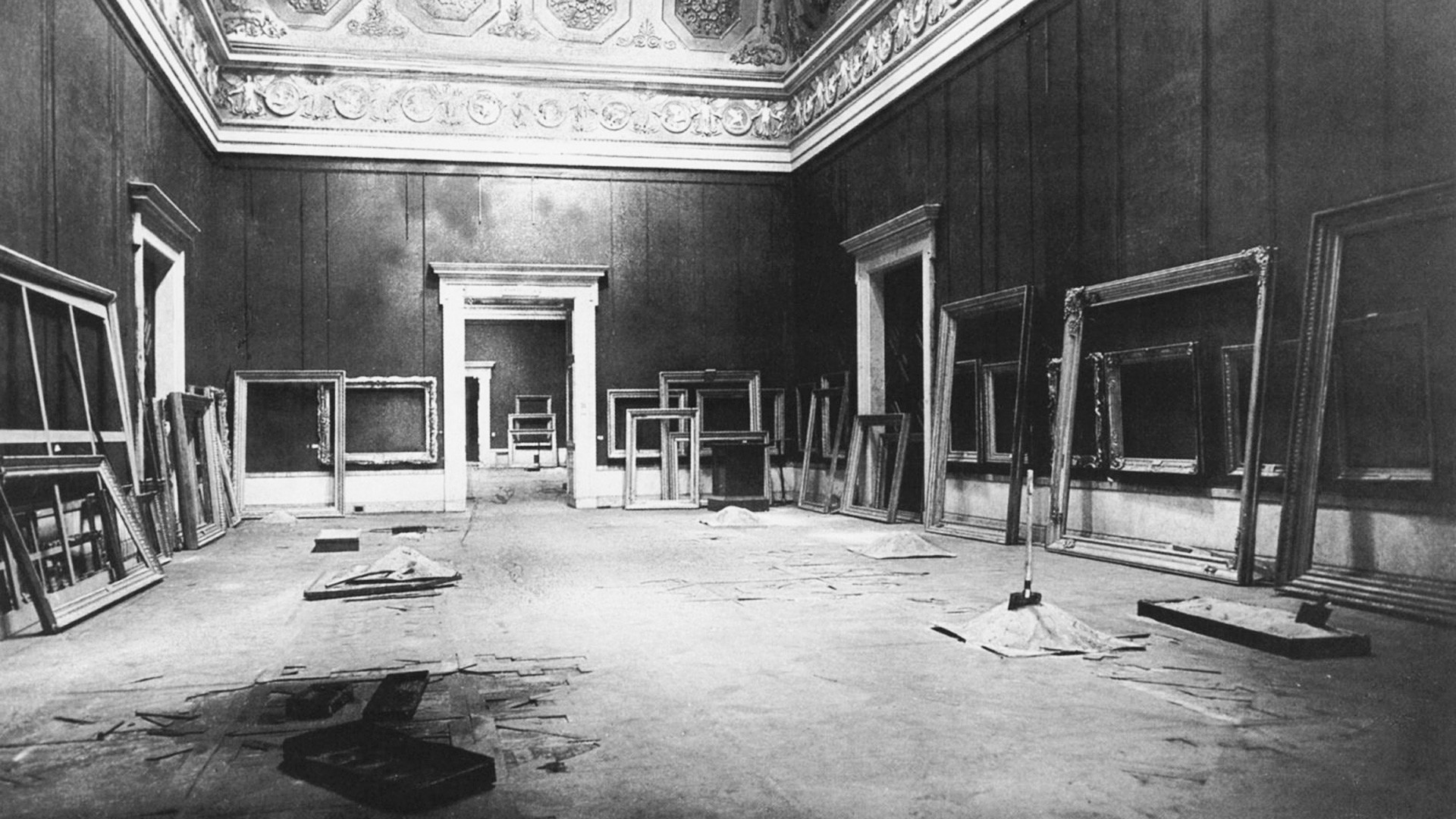

The Armorial Hall, 1942

Boris Kudoyarov/The Hermitage MuseumHowever, on September 8, 1941, the Siege of Leningrad began, and a scheduled train due to carry more Hermitage masterpieces out of the city could not leave. The items were returned to the museum and stored in its basements and on the ground floor.

Carriage garage of the Hermitage damaged by a bomb

The Hermitage MuseumHermitage director Joseph Orbeli and his staff risked their lives in order to protect the building and its remaining treasures. The Hermitage basements were turned into a bomb shelter and several employees with their families went to live there. They were on duty day and night, catching incendiary bombs, extinguishing fires, while all the time fighting for their own lives during the horrible months and years of the Siege.

Jupiter Hall

The Hermitage MuseumVera Milyutina, an artist and an eyewitness of those events, recalled one harsh winter during the Siege and the eerie feeling in the halls of the museum: empty frames, walls covered with hoarfrost, and fragments of broken glass crackling under the feet, sending echoes through the huge halls.

Even during the Siege, however, the Hermitage held some tours and poetry evenings. Incidentally, among the numerous paintings and other treasures in the museum’s collection evacuated during the war, only one was lost - Anthony van Dyck's “St. Sebastian,” which still has not been found.

The Russian Museum in St. Petersburg has the largest collection of Russian art, and the number of paintings alone that had to be removed from the walls and prepared for evacuation were over 7,500. These included more than 60 monumental canvases, measuring 4 or more meters in length. “It took several dozen people to remove from the walls such huge canvases as Karl Bryullov's “The Last Day of Pompeii” and Fyodor's Bruni's “The Copper Serpent,” the museum's director Peter Baltun recalled.

The Russian Museum's staff getting paintings out of their frames

The Russian MuseumHuge canvases measuring between 20 and 60 square meters had to be removed from the frames and also carefully rolled onto special shafts without a single wrinkle and without the slightest damage to the paint layers. Some shafts were up to 10 meters long and with diameters ranging from 60 to 120 centimeters.

The first batch of art works from the Russian Museum were evacuated to Gorky (present-day Nizhny Novgorod; 1,200 km from St. Petersburg) and the second batch went to Perm (1,800 km from St. Petersburg).

Preserving large sculptures in the museum collection was a separate endeavor, Baltun recalled. For example, the famous sculpture by Carlo Rastrelli “Anna Ioannovna with a Little Negro Boy.”

Carlo Rastrelli's statue of Anna Ioannovna

The Russian MuseumJust getting it down from the second floor was a problem, let alone transporting it anywhere. That's why it was decided to bury it in the ground. A deep trench was dug up in the garden in front of the museum, the sculpture was carefully covered in axle grease and wrapped in tar paper. To mark the spot where it was hidden, a flowerbed was planted, which soon was covered with flowers.

A German soldier posing in front of the Peterhof Grand Palace, 1943

Peterhof State Museum-ReserveThe fate that befell this magnificent palace and its exhibits was perhaps the most tragic. About 14,000 art objects from Peterhof were evacuated to Novosibirsk and the city of Sarapul in Udmurtia (1,900 km from St. Petersburg). But only a fraction of the numerous sculptures from the palace's parks were hidden at the freight yard of the city's Moskovsky Railway Station and in St. Isaac's Cathedral (which, incidentally, was never damaged by bombing because it served as a guide for German aviation).

Red army soldiers with recovered paintings stolen from the Peterhof Palace by the Germans, 1945

Getty ImagesAfter all the valuable items were removed, museum staff tried to hide what was left. They buried the remaining sculptures in wooden boxes right in the park and hid bronze statues in the tunnel of the Grand Cascade fountain.

They tried to protect the palaces against bombing, taping their windows, covering the parquet floors with sand, and pasting over wall panels in the halls.

Sculptures burried in the Lower Park of Peterhof, 1944

Peterhof State Museum-ReservePeterhof was not just bombed: it became a battlefield and was almost destroyed. Only charred ruins remained of the Grand Palace, often described as the Russian Versailles. The fountains were destroyed and most of the trees in the park burned. More than 16,000 valuable art objects, including the original sculpture of Samson from the pedestal of the famous fountain, were irretrievably lost.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox