Picasso Room in Shchukin's house.

Heritage Images/Getty ImagesIn 1908, Henri Matisse and a Russian art buyer visited Picasso's studio together. The latter selected two paintings, including Queen Isabeau, and paid generously for both. For the artist, who at the time was rather hard-up, the appearance of this buyer, named Sergei Shchukin, was a godsend. Over a period of six years, the Russian philanthropist bought more than 50 works by Picasso from his Cubist, Rose and Blue periods, including Woman with a Fan and The Absinthe Drinker. His collection of Picasso’s works effectively became the largest in the world. Another famous Russian art collector, Ivan Morozov, showed an interest in Picasso's works as well, acquiring two prominent paintings—Girl on a Ball and Harlequin and His Companion. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Shchukin's and Morozov's collections were nationalized and the Museum of New Western Art was established on their basis. It existed until 1948, when its collection was divided between the Pushkin Museum and the Hermitage.

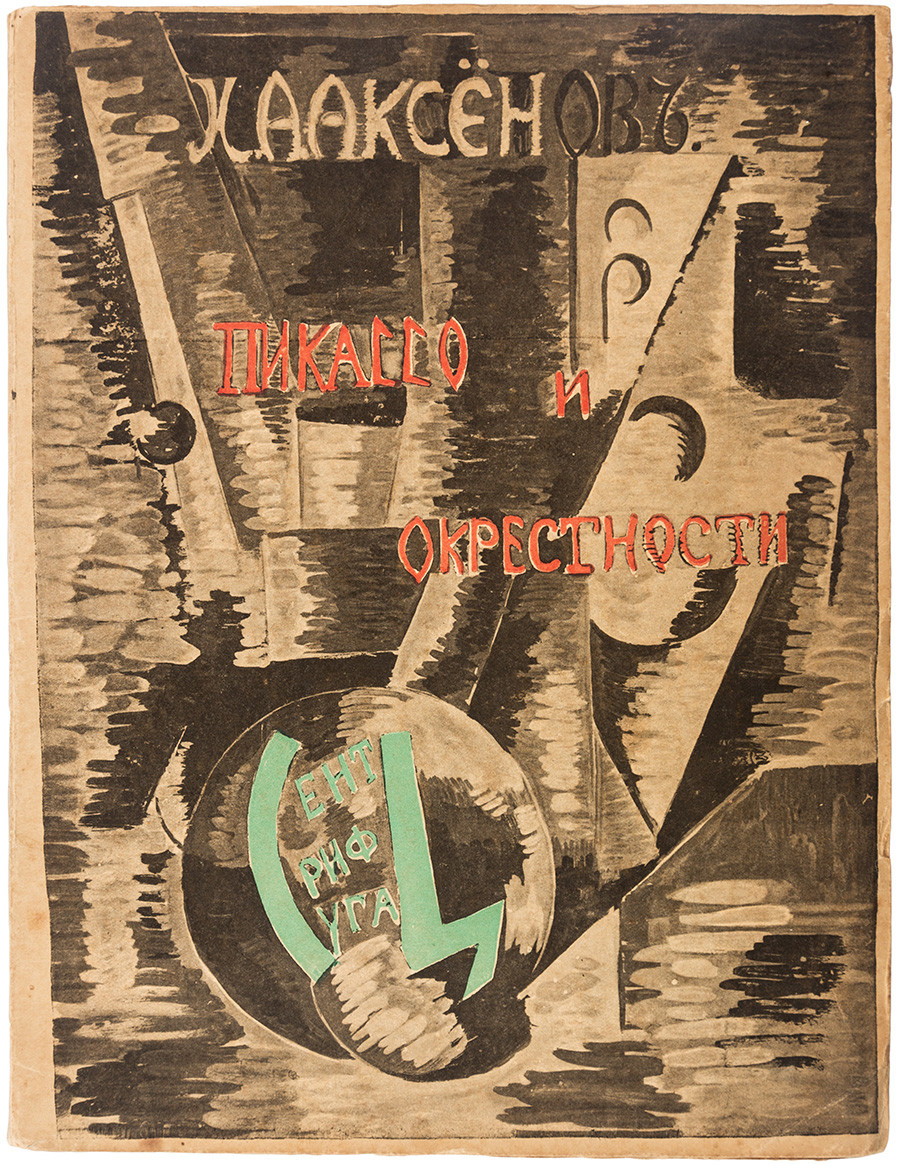

Alexandra Exter, 1917, Pikasso I Okrestnosti (Picasso and Environs), Moscow, Tsentrifuga.

Shapiro AuctionsThe first ever monograph about the artist was published in Russia in 1917. In his paper "Picasso and the Environs," the poet and art critic Ivan Aksyonov, a member of the Centrifuge futuristic association, wanted, as he put it, to warn the public about what they should not be searching for in the Spaniard's works and how they should look at them. Aksyonov must have either visited Paris and met Picasso shortly before the start of World War I, or his source could have been Alexandra Exter, an avant-garde artist who lived in Paris and was familiar with local art criticism (and who, incidentally, designed the cover for his book).

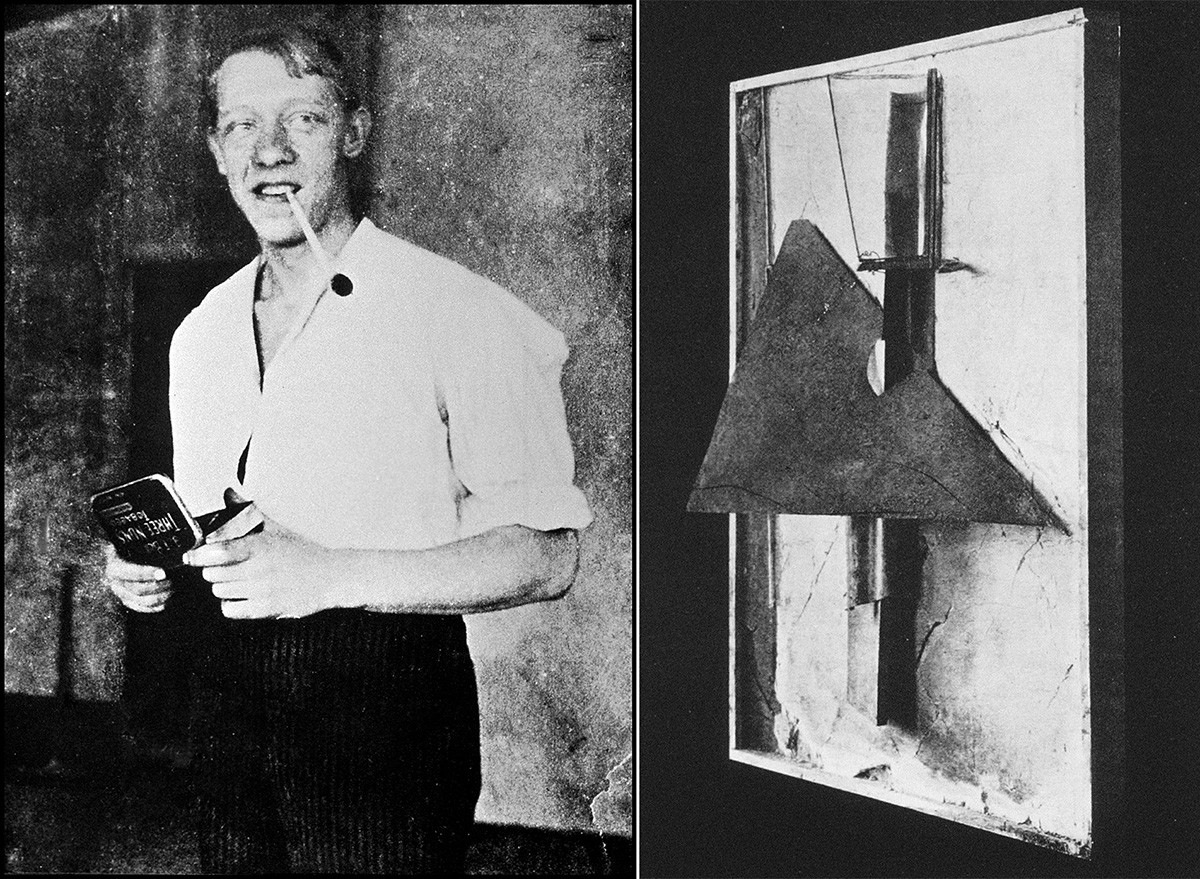

Tatlin's Corner Counter-Relief.

Heritage Images/Getty ImagesRussian avant-garde artists admired Picasso's work, although they had to do so from a distance since the Spaniard was a figure beyond their reach. But then again, what do limitations that even mean to somebody who is passionate about art? In 1914, the artist Vladimir Tatlin traveled to Berlin as a member of a bandura ensemble performing at an exhibition of Russian art. But Berlin was not in fact his final destination. Tatlin dreamed of going to Paris and meeting his idol, and in the end he actually managed to do so. According to one version of events, it was all thanks to Marc Chagall, while according to another he succeeded solely on his own resourcefulness. Tatlin put on some eye-catching clothes and settled down with his bandura outside Picasso's studio. Picasso noticed this unusual character and invited him in to sit for a painting. The moment the Spaniard left the room, Tatlin began to frantically make sketches of everything he saw around him until Picasso returned and kicked the "sitter" out. According to another theory, Tatlin admired Picasso so much that when they met, he immediately offered to become his servant in the hope of finding a way to discover the secret of his genius. Whatever actually took place in reality, Tatlin regarded Picasso as his teacher and after his return from Paris focused on creating counter-reliefs.

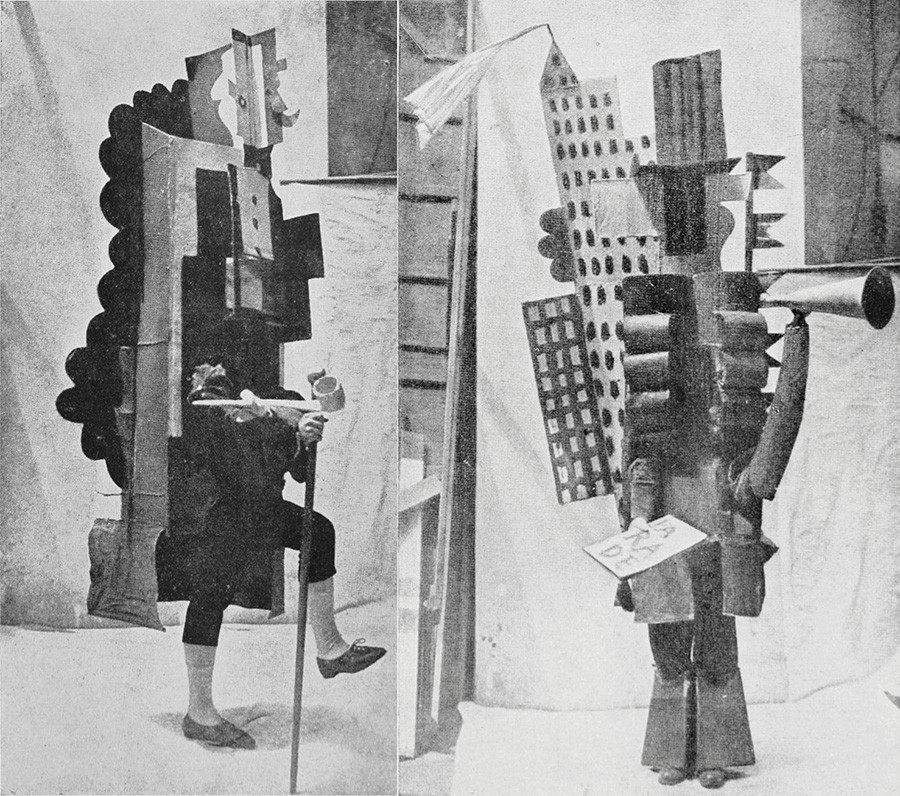

Costume design by Pablo Picasso for Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes performance of Parade at Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris 18 May, 1917.

Public domainIn the spring of 1917, Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes had a new production at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. This time the famous impresario had decided to combine art, ballet and poetry into the one-act ballet Parade. The ballet, which was based on poems by Jean Cocteau, was created by choreographer Leonide Massine and composer Erik Satie, while the scenery, costumes and the circus-inspired curtain were designed by Pablo Picasso.

The result exceeded all expectations. Instead of ballet tutus, the dancers were dressed in bulky costumes made of papier-mâché, wood and metal, which were so uncomfortable that any attempt at movement in them looked mechanical and awkward. Against the background of Cubist scenery, the dancers were transformed into moving fragments of a collage. Thus Cubism made its first foray into the world of theater, while Parade became one of the first Surrealist events.

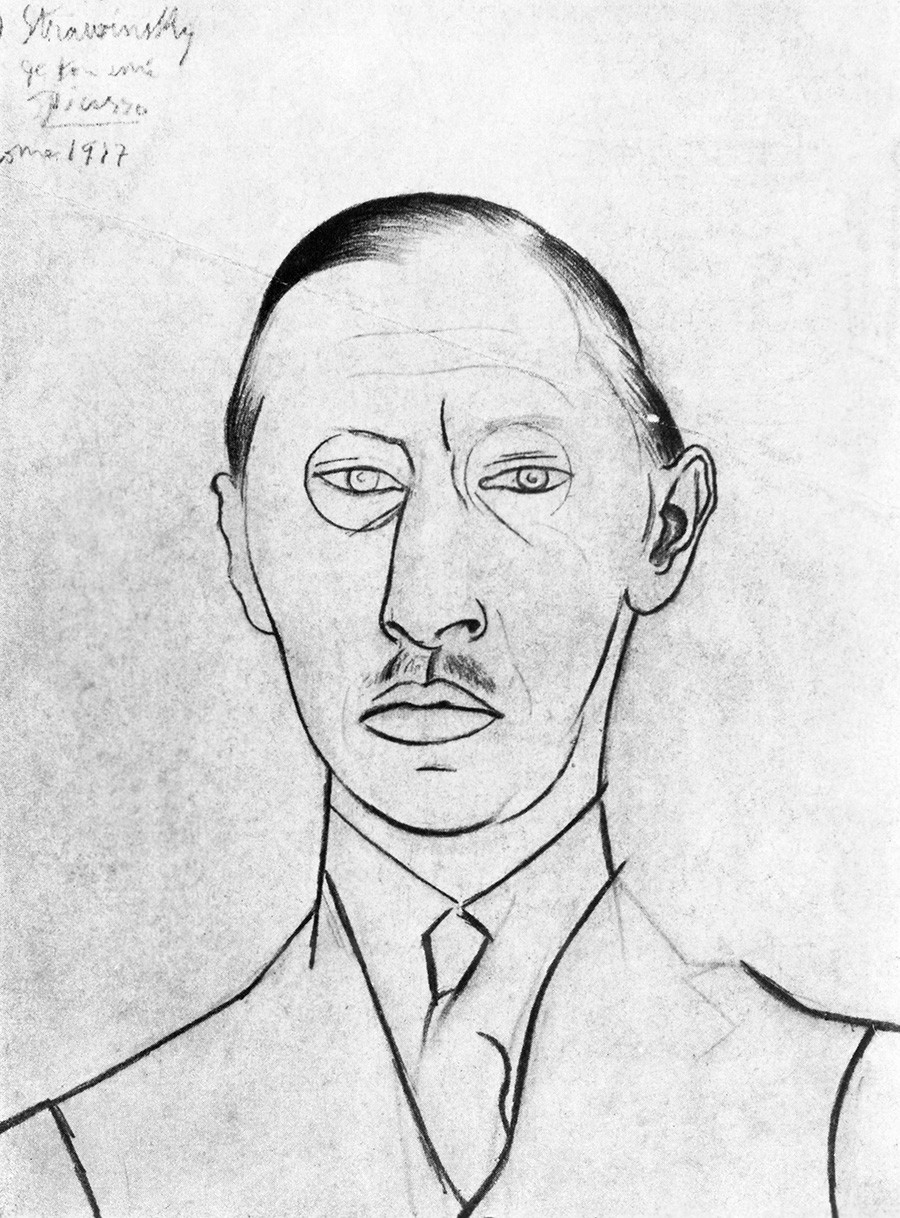

Sketch of Famous Composer Igor Stravinsky by Pablo Picasso.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesTo prepare the sets and costumes for Parade, Picasso went to Rome, where he met Igor Stravinsky. They became friends, and their soon friendship evolved into professional collaboration when Picasso worked as a designer on Stravinsky's ballet Pulcinella and painted several portraits of the musician. Stravinsky tried to take one of these with him to Switzerland, but border officials demanded to know what it was and refused to believe that it was a pencil drawing by a famous artist since it looked more like a blueprint. The composer agreed that Picasso's work was indeed nothing more than a blueprint of his face. In the end, the portrait had to be sent by diplomatic mail through the British Embassy.

Pablo Picasso and Olga Khokhlova in the painting studio in London, 1919.

Heritage Images/Getty ImagesIn Rome, Picasso met Olga Khokhlova, a ballerina with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. Picasso and Khokhlova got married in the summer of 1918. The ceremony took place at the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Paris and was attended by, among others, Gertrude Stein and Sergei Diaghilev. In 1921, the couple had a son, Paulo, and in 1935 they split up, although they never officially got divorced.

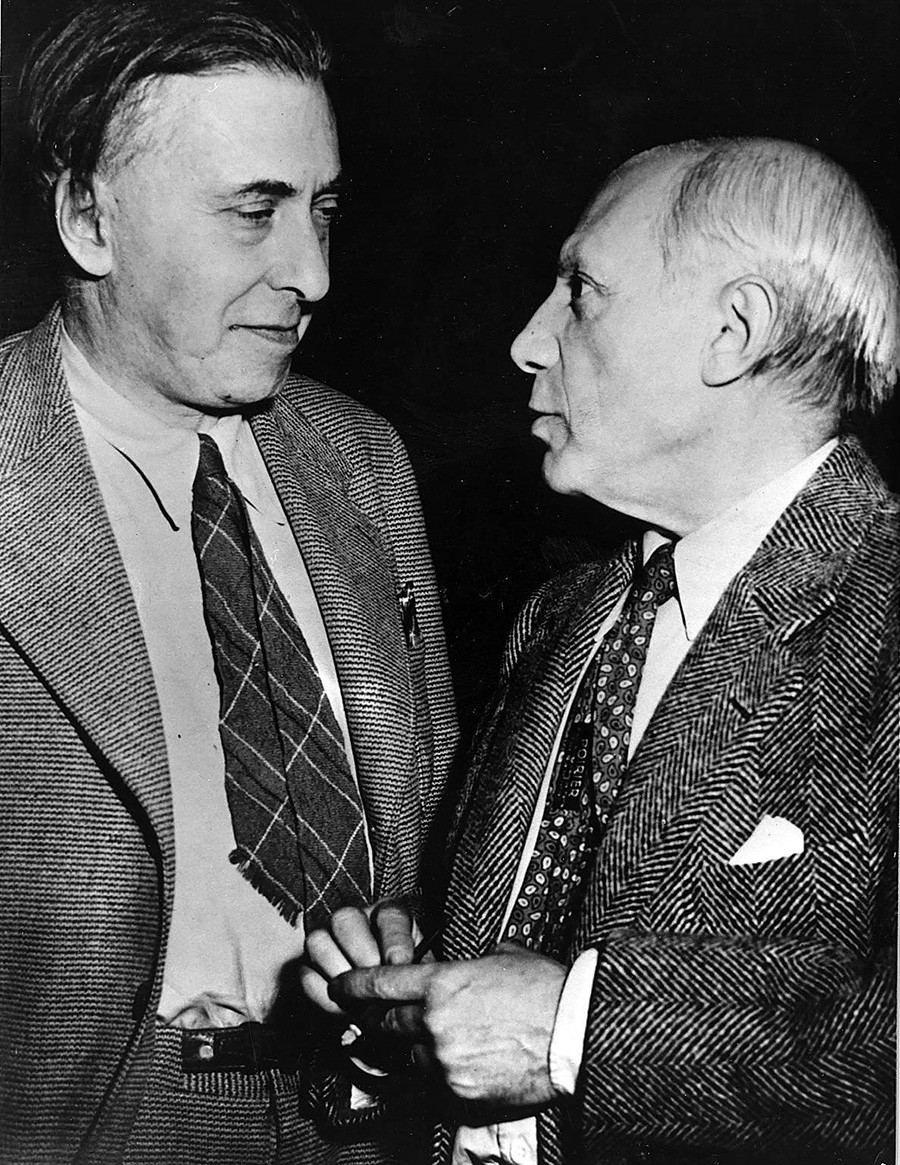

Picasso became friends with the writer Ilya Ehrenburg in 1914. Ehrenburg admired what he described as the "destructive power" of Picasso's art, and he half-jokingly called the Spaniard a good devil. Picasso once decided to paint a portrait of Ehrenburg, but just as the latter made himself comfortable in an armchair preparing to pose, Picasso announced that he was finished. Ehrenburg was surprised at how quickly the portrait was finished, to which Pablo laughingly replied they had after all known each other for more than 40 years, and all this time had been training for how to paint portraits in just five minutes.

Exhibition of Pablo Picasso in Moscow.

Emmanuel Evzerikhin/TASS/Russia in photoIt was Ehrenburg who introduced the Soviet public to Picasso and helped organize exhibitions of his work in the Pushkin Museum and the Hermitage in 1956. The exhibitions became a harbinger of the approaching political thaw, with such enormous excitement around them that people would stand in line all night long in order to get in. Ehrenburg famously tried to reassure the public with the line, "You have waited for this exhibition for 25 years, can you wait for 25 more minutes please?"

In the Soviet Union, Picasso was sometimes referred to as "Comrade Pablo" since he joined the French Communist Party in 1944. That was his way of protesting against the war and horrors perpetrated by the Franco regime in his native Spain. When Joseph Stalin died in 1953, Picasso painted his portrait, but to the communists' outrage he depicted Stalin as a young man. This turned into something of a scandal when members of the French Communist Party voiced their indignation that Stalin had been presented in a non-canonical image. For his part, the poet Louis Aragon, who was editor-in-chief of Les Lettres Françaises, which had printed the portrait, reproached his friend: "Stalin cannot be invented."

A poster for World Congress of Partisans for Peace, 1949.

Legion MediaIn 1949, Paris hosted a World Congress of Partisans for Peace, and Picasso created a poster depicting a dove for the forum. The symbol soon became globally famous, and the artist would use it many times afterwards. In 1962, he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize, which was brought to him in Mougins in France by his friend Ilya Ehrenburg.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox