Nabokov novels should come with a warning that says: Addictive! Written in a striking style, they have to be read and reread time and over again, evoking new meanings and interpretations. The inimitable Nabokovian language has a champagne sparkle spiced up by cinnamon wisdom.

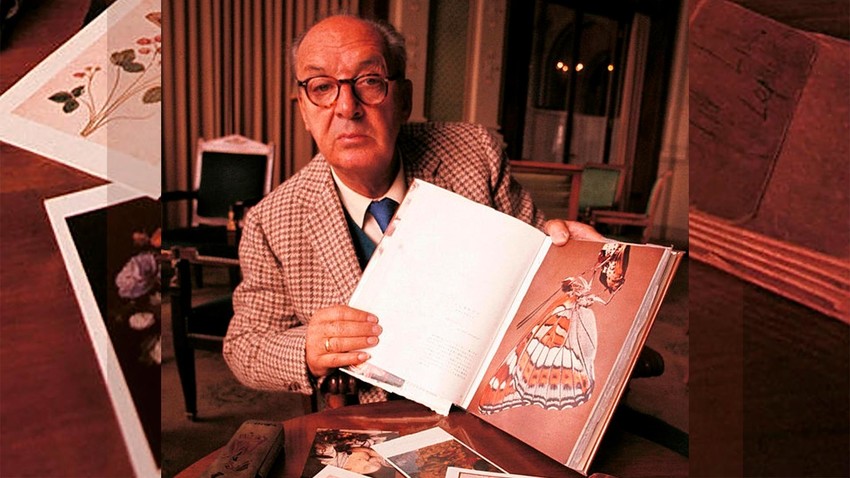

Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) said he dreamed of turning his readers into spectators. His dream had come true in his lifetime. The writer made his readers sink into the semantic abyss of his texts. Reading Nabokov might seem like a linguistic challenge at first. But then, after a few pages, you get used to it, with contradictions vanishing like fluttering butterflies. “Literature and butterflies are the two sweetest passions known to man,” Nabokov, who had an over 4,300-specimen collection of exotic and rare butterflies, said. “I discovered in nature the non utilitarian delights I sought in art. Both were a form of magic, both were a game of intricate enchantment and deception.”

‘Mary’ is about first romance, bittersweet nostalgia and regret.

Nabokov’s debut novel, initially entitled ‘Happiness’, has a lot of autobiographical details. The novel is set in a Russian boarding house in Berlin. The protagonist, émigré Lev Ganin, is caught unawares when he finds out that his neighbor’s wife is his former first love, Mary. Ganin plots a devious plan to meet her at a train station, after many years. Mary is the blast from the past, a dreamlike symbol of a bygone era and happiness, in other words, “all his youth, his Russia”. At the last moment, Ganin decides that time travel to the past is impossible and abandons both Berlin and Mary, forever. “The thick happiness of first love is unique,” Nabokov would later note in his ‘Laughter in the Dark’.

Nabokov began writing ‘Mary’ in 1924. By the end of the year, two chapters had been written, but the writer destroyed the manuscript, retaining only a fragment that was published in January 1925 under the title ‘A Letter to Russia’. Nabokov returned to the idea of writing the novel in the spring of 1925, having married Vera Slonim (his wife of 52 years), to whom he eventually dedicated the novel. It was published in Berlin in 1926 under the pen name Vladimir Sirin.

“I am an American writer, born in Russia, educated in England, where I studied French literature before moving to Germany for fifteen years. ... My mind speaks English, my heart speaks Russian and my ear speaks French,” Vladimir Nabokov said about himself.

Written in English, ‘Look at the Harlequins’, Nabokov’s last finished novel, depicts a famous Russian-American writer named Vadim Vadimovich N., who recalls a series of personal stories from his unsuccessful marriages and love affairs, as well as an epic trip to the USSR with a fake passport. Nabokov, who had never visited Russia after his family left the country in 1919, drew valuable insights of this made-up trip from his sister Elena, who went back to her native Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) several times in the 1960s.

Although the plot is quite complicated, you’ll probably read this short novella in a 90-minute burst, wishing it were a bit longer.

Written just five years before the writer’s death, ‘Transparent Things’ is Nabokov’s late meditation about love, death and time, full of bitter irony and philosophical musings. Like this one: “It is generally assumed that if man were to establish the fact of survival after death, he would also solve, or be on the way to solving, the riddle of Being. Alas, the two problems do not necessarily overlap or blend.”

Beware: It’s Nabokov’s longest, most complex novel.

Filled with riddles, parables and allusions, it’s somewhat puzzling. ‘Ada’ is rough in that the book has its moments of pure genius, while at times the novel suffers from redundancy. So, it’s not for everyone. For instance, author of ‘Time’s Arrow’ British novelist Martin Amis owned up, “At least half a dozen times I have tried and promptly failed, to read Ada.” The plot of Nabokov’s 15th novel revolves around an incestuous affair between Ada and Van, sister and brother, set against an idyllic backdrop of a fictional planet called Antiterra.

Hermann, a German merchant of Russian descent, is plotting a crime poised to become a genuine masterpiece of daring ingenuity. It turns out, however, that life itself is the most ridiculous game whose plausibility often distorts reality.

After Nabokov’s ‘Despair’ saw the light of day in 1936, Russian poet and literary critic Gleb Struve had stated: “What is the main property of Sirin's [Nabokov’s pseudonym) creativity? I would define it as joyful and conscious creative arbitrariness. No other writer gives you such an overwhelming impression of creative, magically light power over his world. Sirin doesn’t depict life, he creates in a plane parallel to it.” Indeed, Nabokov had no rivals when it came to capturing an amalgam of human sensations.

Written in Berlin, ‘The Eye’ is one of the most mysterious and witty works by Nabokov, in which the signature features of the mature writer's style fully manifested themselves.

Originally written in Russian, it’s Nabokov’s shortest, virtuoso novel. The main character, a Russian émigré living in Berlin, is beaten by the jealous husband of his mistress. Unable to survive the humiliation, the protagonist decides to commit suicide, but only succeeds in hurting himself. His near-death emotional experience changes the protagonist’s life. ‘The Eye’ is often compared to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s ‘Notes from Underground’ and it’s not hard to see why. Both tackle the essence of human life. “There is a titillating pleasure in looking back at the past and asking oneself, ‘What would have happened if…’ and substituting one chance occurrence for another, observing how, from a gray, barren, humdrum moment in one’s life, there grows forth a marvelous rosy event that in reality had failed to flower…”

READ MORE: Top 5 Fyodor Dostoevsky MASTERPIECES

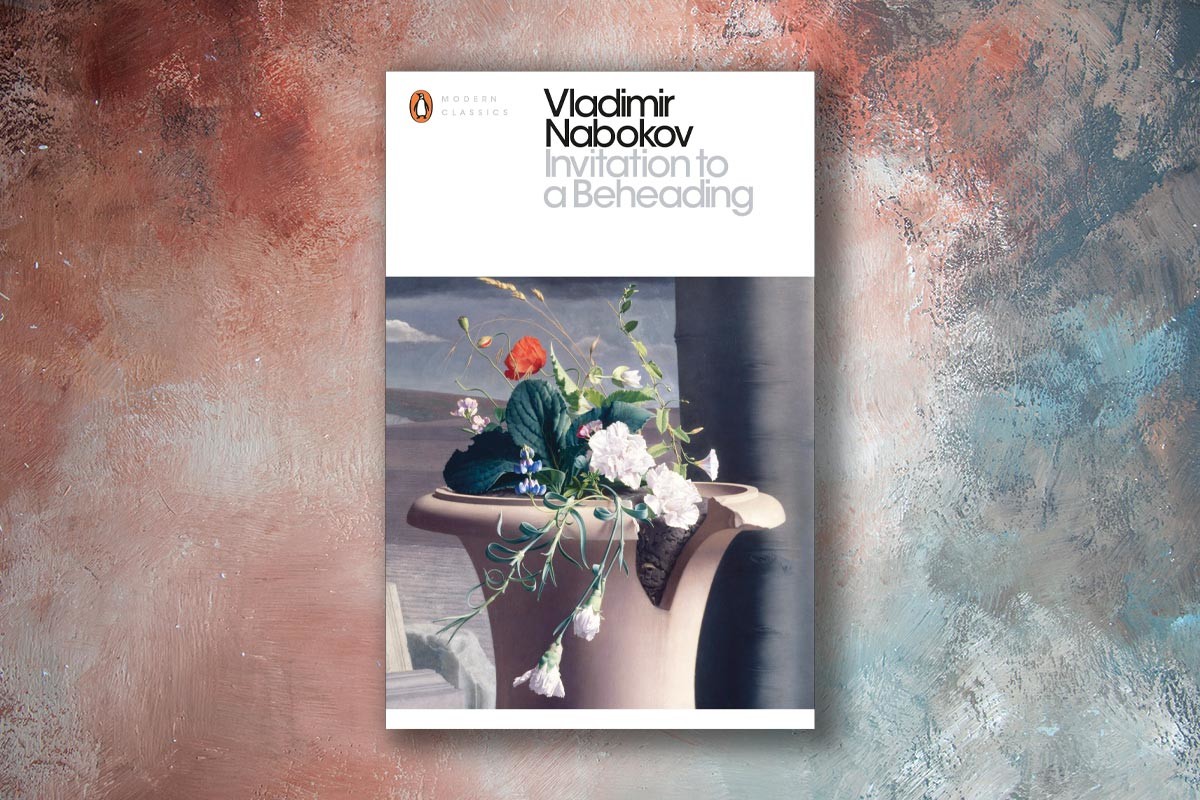

Nabokov’s second novel written in English stands shoulder to shoulder with ‘The Trial’ by Franz Kafka and George Orwell’s ‘1984’ in its stylistic brilliance, intellectual beauty and philosophical depth.

The title of the disturbing dystopian novel is associated with Nabokov’s attitude to the “ominously leftist world”, to the spread of communism and fascism. The events of the complex novel take place in an unnamed country in the city of Padukgrad, where a dictatorial regime has just been established as a result of the revolution. The ruling “Party of the Average Man” is run by dictator Paduk. Adam Krug, a revered philosopher, is asked to support the party, run by his former classmate. What if he says no? “Nothing on earth really matters, there is nothing to fear and death is but a question of style, a mere literary device, a musical resolution,” Nabokov, who was nominated for the Nobel prize in literature several times, wrote in ‘Bend Sinister’.

This is the first book written by Nabokov in English. “Sebastian Knight was born on the thirty-first of December, 1899, in the former capital of my country.”

The opening phrase of the story is said by Sebastian’s half-brother, designated in the novel by the abbreviation ‘V.’ Sebastian Knight is a famous Russian writer, who wrote in English and died in a Paris hospital. V. restores and deconstructs the life of his brother, piece by piece, making Nabokov’s intricate and multi-layered novel come alive.

Nabokov’s fifth novel is about the formation of character and maturity.

“Great novels are above all great fairy tales… literature does not tell the truth but makes it up,” the writer said. The fairy-tale motifs in ‘Glory’ are related to the protagonist, a romantic young man, fascinated by the world of fairy tales and knightly legends since childhood. Martin Edelweiss is half-Swiss. Born and raised in St. Petersburg, he is forced to leave Russia for Europe with his mother after the revolution. He travels a lot, plays tennis (Nabokov was a big fan of tennis, too), studies philology at Cambridge and falls in love with Sonia, but the feeling is not mutual. To win the heart of his beloved, the young man has to face the fear and do something risky. Nabokov said that ‘Glory’ is about “overcoming fear, about the triumph and bliss of this feat”.

READ MORE: Top 10 CRUCIAL fictional male characters in Russian literature

Domestic life, adultery and malice – what could be more banal. Not for a daredevil writer like Vladimir Nabokov, a master of suspense of the highest caliber.

A darned-good juggler, Nabokov turns the seemingly trivial storyline into a thrilling puzzle, a page turner. Poor Franz arrives in the German capital to work with his well-off uncle and falls for his idle wife, Martha, 13 years his senior. Nabokov’s second novel written in Russian and set in Berlin will knock you off with an unexpected ending. ‘King, Queen, Knave’ is a balancing act between the banality of a literary cliché and a witty parody. It’s also Nabokov’s unorthodox answer to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime and Punishment’.

It’s a skillfully crafted novel about a Russian chess player who is obsessed with chess to the point where he gradually loses all touch with reality.

In ‘The Luzhin Defense’, Nabokov kills two birds with one stone. He brilliantly describes the phantasmagoric metamorphosis of the protagonist, whose full name is mentioned only in the final sentence of the novel and reshapes the reader's world view in such a way that we begin to see the novel entirely through the prism of a chess game. That’s checkmate, for sure!

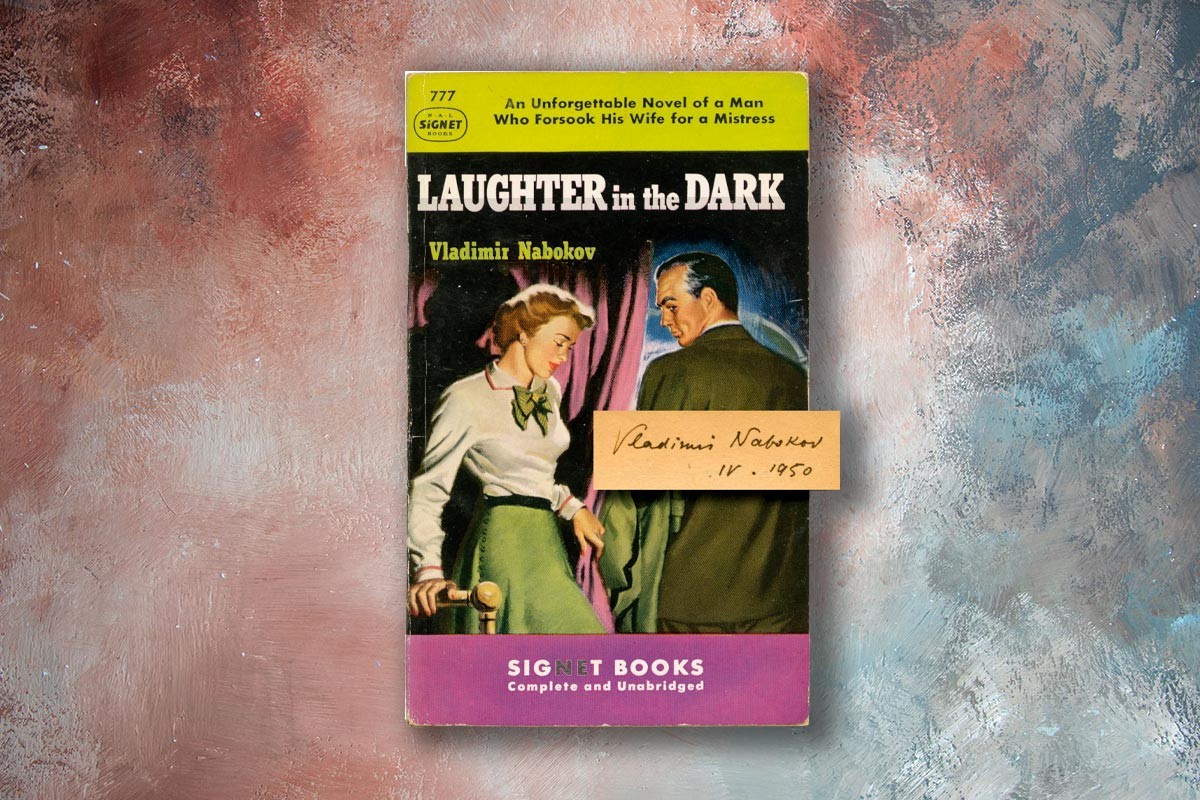

Nabokov’s most dashing and hopeless thriller novel is set in Germany in the 1920s.

It was originally written in Russian (Nabokov later translated it into English himself). ‘Laughter in the Dark’ is about a fatal attraction of a successful, wealthy and happily married German art critic named Bruno Kretschmar (Albert Albinius in the English version of the novel) for a young wannabe starlet named Magda Peters (Margot), who is dreaming of Hollywood and works as an usherette in a cinema house. The young gold digger forces the protagonist to leave his wife and daughter, but later, robs Bruno in tandem with her new lover. Kretschmar gets into a car accident, goes blind and dies. Nabokov described ‘Laughter in the Dark’ as his “worst novel”.

“It’s not particularly good. It’s a little crude...” he said. And yet, the writer noted, in an interview with The New York Times, that it was “the only book that brought me in a little money now and then”.

It’s Nabokov’s last novel written in Germany before moving to France in 1937.

While the grim reality of the Nazi Germany is reflected in the concept of his magnum opus, Nabokov objected to describing his novel as a political pamphlet. The writer considered the ‘Invitation to a Beheading’ his best work and his “only poem in prose”. Whatever you call it, one thing is certain: It’s a timeless masterpiece about the tyranny of triviality (or, rather, ‘poshlost’, the one thing Nabokov really despised) and how to battle it with the help of the “ancient inborn art of writing”.

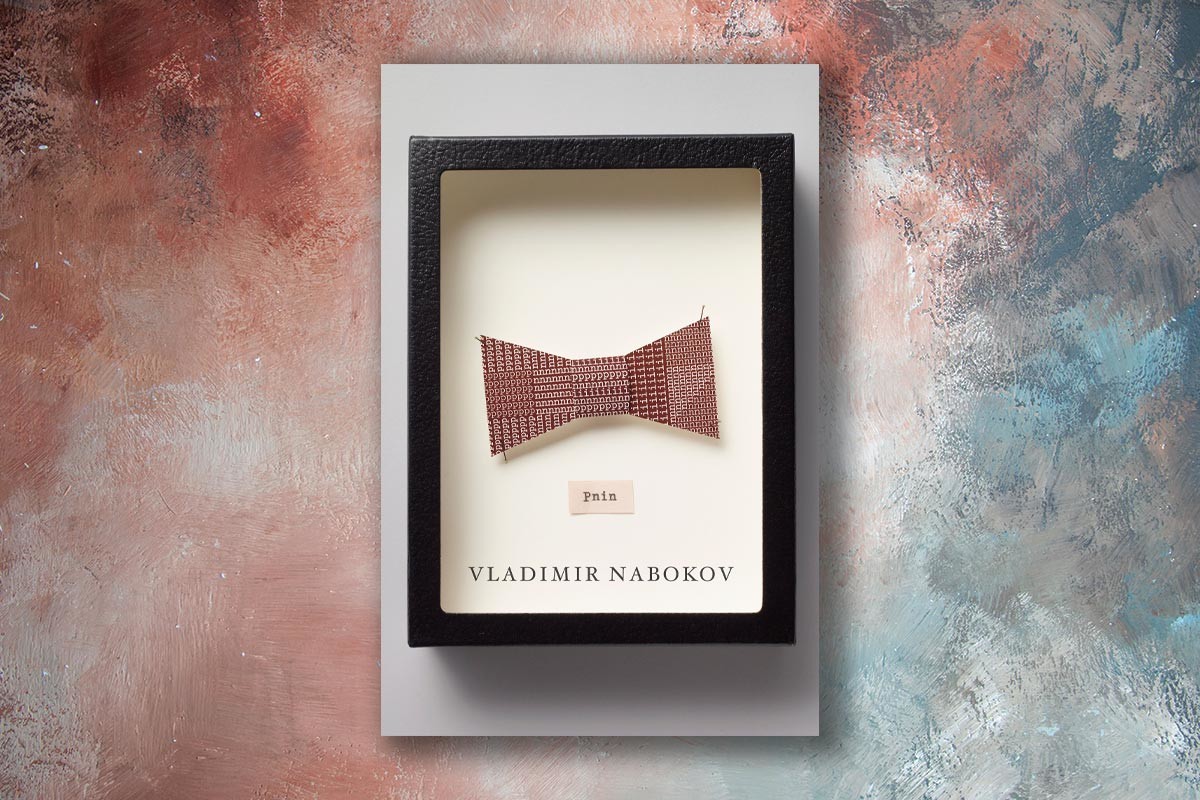

‘Pnin’ is often referred to as Nabokov’s most humanistic novel, imbued with innocent irony and compassion for the charmingly awkward title character, Prof. Timofey Pnin.

A Russian émigré, Pnin finds himself in the United States having lost everything (except for his passion for science) in his life. Pnin cherishes some warm memories of his home in St. Petersburg, his first love and his failed marriage. “The history of man is the history of pain,” Nabokov wrote. The funny thing is that although Pnin’s life is quite miserable, the pathetic protagonist constantly finds himself in comic situations, inspired by Nabokov’s own teaching experience at Wellesley College and Cornell University.

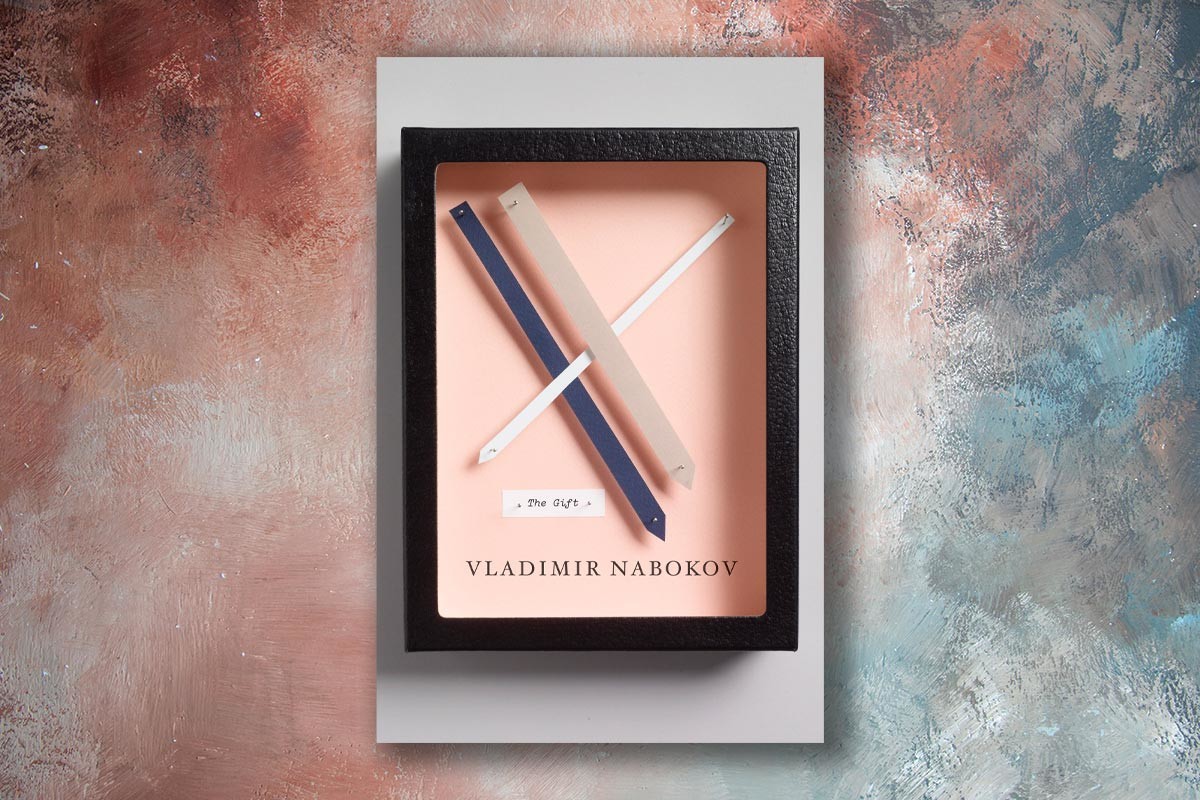

Nabokov’s last tour de force written in Russian is widely considered the pinnacle of his creative achievement.

‘The Gift’ took four years to write. Philosophically speaking, it’s metafiction. It describes the nuts and bolts of the creation of text. The novel has a mille-feuille structure and is rich in food for thought. ‘The Gift’ is also a story about life and death and an artist’s place in history. After reading the novel, translator Georgy Hessen, told Nabokov: “I just read your Gift and I want to tell you — you are [a] genius! If your chess or tennis or football were remotely like your writing, you old scoundrel, you could concede Alekhine [the fourth world champion] a pawn and Budge 15 points and make Hiden [Rudolf ‘Rudi’ Hiden, one of the best goalkeepers of the 20th century] a reserve goalkeeper in any professional team.” Given that Nabokov was a brilliant chess player and a pretty good goalkeeper, his friend’s ironic review summed it all up, really.

One of the most extravagant masterpieces in history, ‘Pale Fire’ holds a special place in world literature.

Its genre is hard to define (some literary critics classify it as an “anti-novel”). ‘Pale Fire’ consists of four parts: the publisher's foreword; a 999-line poem by John Shade, a gargantuan commentary and a supplementary index by Shade’s peer, Charles Kinbote.

‘Pale Fire’ is listed among the All-Time 100 English-language novels by Time Magazine. It can hardly be called a novel, though. While it pretends to be a purely philological text awash with quirky allusions, in reality it’s a reflection about distortions and frictions that inevitably arise between the author and his readers.

Nabokov wrote his most famous novel in English and translated it into Russian twelve years later.

The story of an adult man (Humbert Humbert) who loses his moral compass and finds the love of his life in the form of a 12-year-old girl named Lolita broke conventions and taboos. ‘Lolita’ is not a novel about sin, but a saga of obsession, infatuation and self-flagellation. The perverted relationship between Lolita (whom Nabokov called “my poor girl”) and pedophile villain Humbert Humbert, who move from one motel to another like in a classic road movie, is often seen as a grander metaphor for the collision of the old and new worlds, the decrepit old Europe and the young and provocative America.

When Nabokov was asked which of his books was the hardest to write, he immediately replied: “Oh, Lolita, naturally.”

“I lacked the necessary information — that was the initial difficulty. I did not know any American 12-year-old girls and I did not know America; I had to invent America and Lolita. It had taken me some 40 years to invent Russia and Western Europe and now I was faced by a similar task, with a lesser amount of time at my disposal,” Nabokov said in an interview with Playboy Magazine.

Nabokov worked on ‘Lolita’ for around eight years, with frequent interruptions. The writer had bouts of despair and even allegedly wanted to burn the draft of the novel at some point. Luckily, his wise wife Vera stepped in just in time...

READ MORE: Top 5 Russian writers who tried to destigmatize sex

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox