Russian thinkers have been arguing for centuries about whether the country should choose a European path of development or concentrate on its own uniqueness, or perhaps to borrow more from its Asian neighbors (read more about this idea here).

The great 19th century writer, Leo Tolstoy, true to his idiosyncratic nature, didn’t fall into any of these camps. He had a unique take on whether Russia needs Europe and its values.

Tolstoy was extremely critical of the Russian reality in which he lived, complaining about the "patriarchal barbarism, theft and lawlessness" (as he put it in a letter to his Aunt Alexandra) that reigned in his homeland. At the same time, he was fascinated by certain European thinkers and held them in high regard.

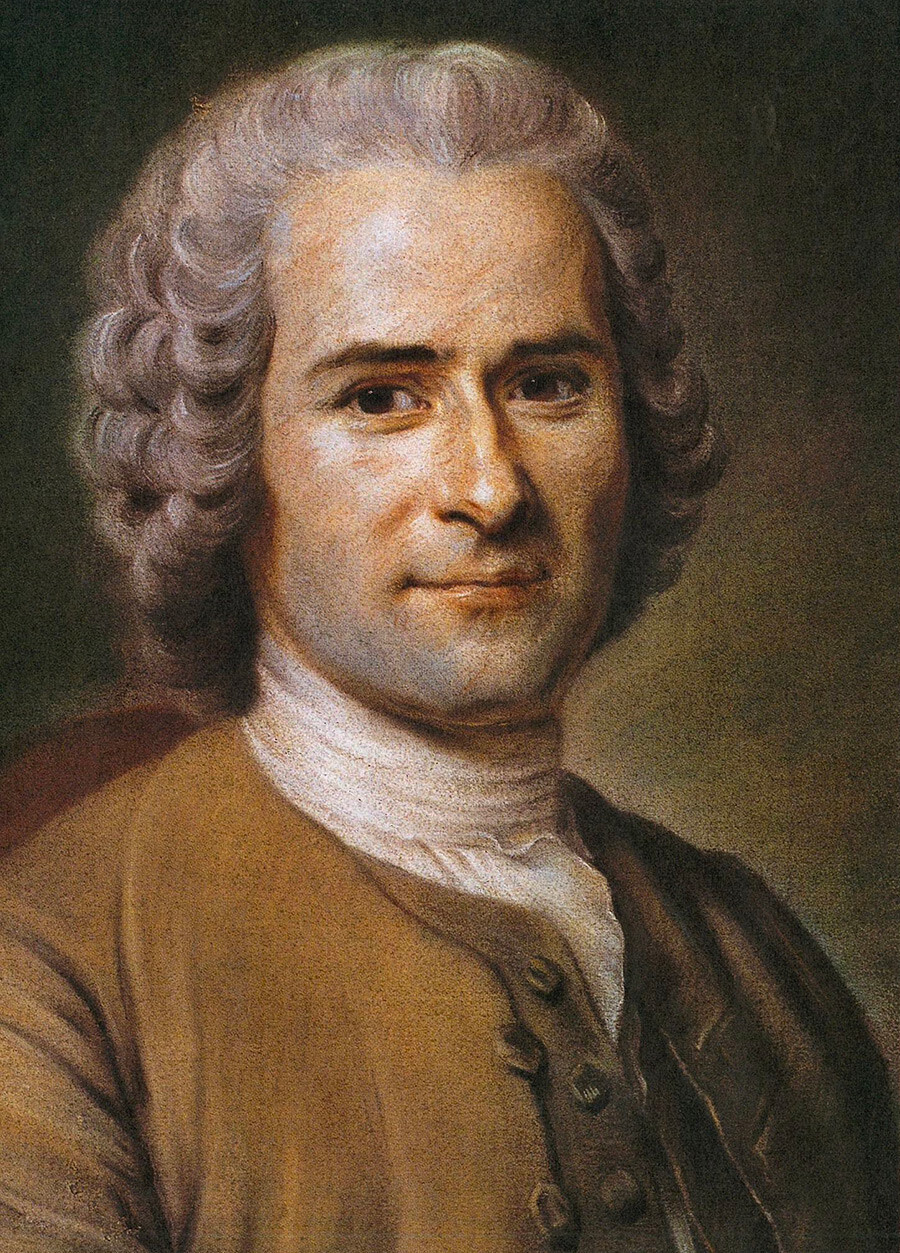

When Tolstoy was just 15 years old, he came across the works of French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and read all 12 volumes in one go. The "father of European democracy" had a great impact on the teenager. Rousseau contrasted the "natural state" of humankind with civil society, believed that private property was the cause of inequality and advocated rule by the people.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Musée Antoine-LécuyerAll these ideas embedded themselves deep in the psyche of the young Tolstoy and essentially formed the basis of his belief system for the rest of his life. Five years before his death, he wrote: "Rousseau has been my teacher from the age of 15. I had two great and beneficent influences in my life: the influence of Rousseau and of the Gospels."

Despite the fact that Tolstoy spoke so highly of the European thinker, he was critical of contemporary Europe and believed that the condition of Western societies was even worse than that of Russia, and for this reason it was pointless to see them as an example to follow.

Tolstoy may have had some hopes and illusions regarding European reality in his early youth. He came away disappointed from a trip to Europe in 1857, which he made in order to study European teaching methods and the educational system (Tolstoy wanted to open schools for peasant children on his estate and in the surrounding area). He didn't find anything new or useful in European schools and, furthermore, he was shocked by the customs and morals that prevailed there.

He was shaken to the core by a public execution using the guillotine that he witnessed in Paris, (during this trip Tolstoy also visited Italy and Switzerland). In France at that time, such executions were a common occurrence and a form of entertainment drawing huge crowds of onlookers. Public spectacles of this kind were unthinkable even in "barbaric" Russia (public executions were abolished long before the writer's birth). Tolstoy was shocked by the fact that the killing of a man was turned into a spectacle and that the execution was automated and carried out by a machine specially invented for the purpose. This event led him to draw far-reaching conclusions about the essential nature of European states.

A view of the front of the Opera de Paris, between 1880 and 1900

Brown University LibraryAt the same time, Tolstoy was unpleasantly surprised by the "free love" that European society regarded as normal. He wrote that 19 of the 36 couples resident at the boarding house where he stayed in Europe were unmarried. This reaction was not the result of any prudishness on the writer's part: Tolstoy himself openly admitted his weakness for women, spent his whole life struggling against sexual passions and regarded "carnal desires" as one of the main human sins leading to all the others. The writer believed that society's "normalization" of carnal sin ultimately led to the premeditated corruption of a nation.

Tolstoy’s impressions about Europe and its values and freedoms while still a young man only became stronger and more radical with the passage of time. "The people of Europe and America are in the position of a man who is so far advanced along a path which initially appeared to him the right one, but who has increasingly been diverted from his goal the more he has continued along it, that he dreads having to admit his mistake," he wrote in 1905 in his article "A Great Iniquity".

Tolstoy's view was that, for all their iniquity, the Russians, unlike Westerners, had not yet strayed from their designated course and were still capable of adhering to the true path. But he was mortified that, instead of continuing on this path, Russia was "in everything slavishly imitating what is going on in Europe and America". Tolstoy regarded this as a huge mistake.

The Russian people were being urged by their leaders to follow "in the rear of the dying-out and misguided European and American nations, and with all possible dispatch to become corrupted and to relinquish their own calling in order to resemble Europeans," Tolstoy wrote.

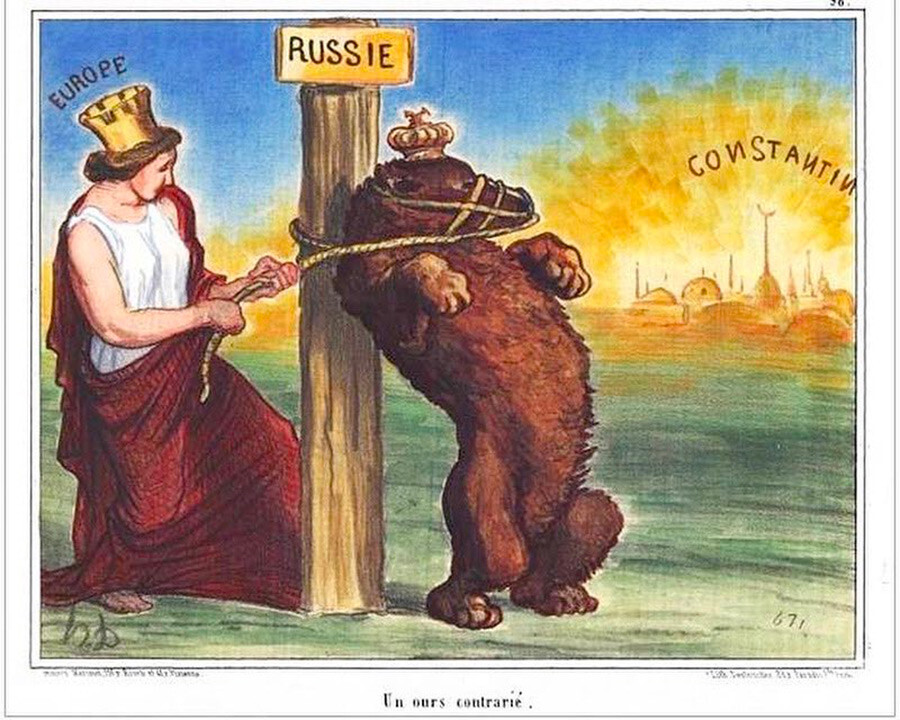

French illustration from the Crimean War (1854) showing Europe holding the Russian bear back from capturing Constantinople

Le Charivari, illustrated by Honoré DaumierAll of European history, according to Tolstoy, is a history of stupid and reprobate rulers "killing, despoiling and, most importantly, corrupting their people". In his article "The One Thing Needed. Concerning State Power", Tolstoy lumps together the "debauched Henry VIII", the "malefactor Cromwell" and the "hypocrite Charles I"... (It has to be said that Tolstoy did not idealize Russian tsars either.)

The writer was upset that some groups of noblemen in Russia wanted to establish forms of political culture much like in Europe and America that "claim to ensure the liberty and well-being of all citizens". In Tolstoy’s view, Russia didn’t need to think "about press freedom, religious tolerance, freedom of association, tariffs, suspended sentences or the separation of church and state", as was the case in Europe.

The main thing, according to Tolstoy, was that Russia shouldn’t be transformed from a peasant country into a proletarian one. He considered the peasant way of life to be the most ethical and legitimate social structure and lifestyle for the nation.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox