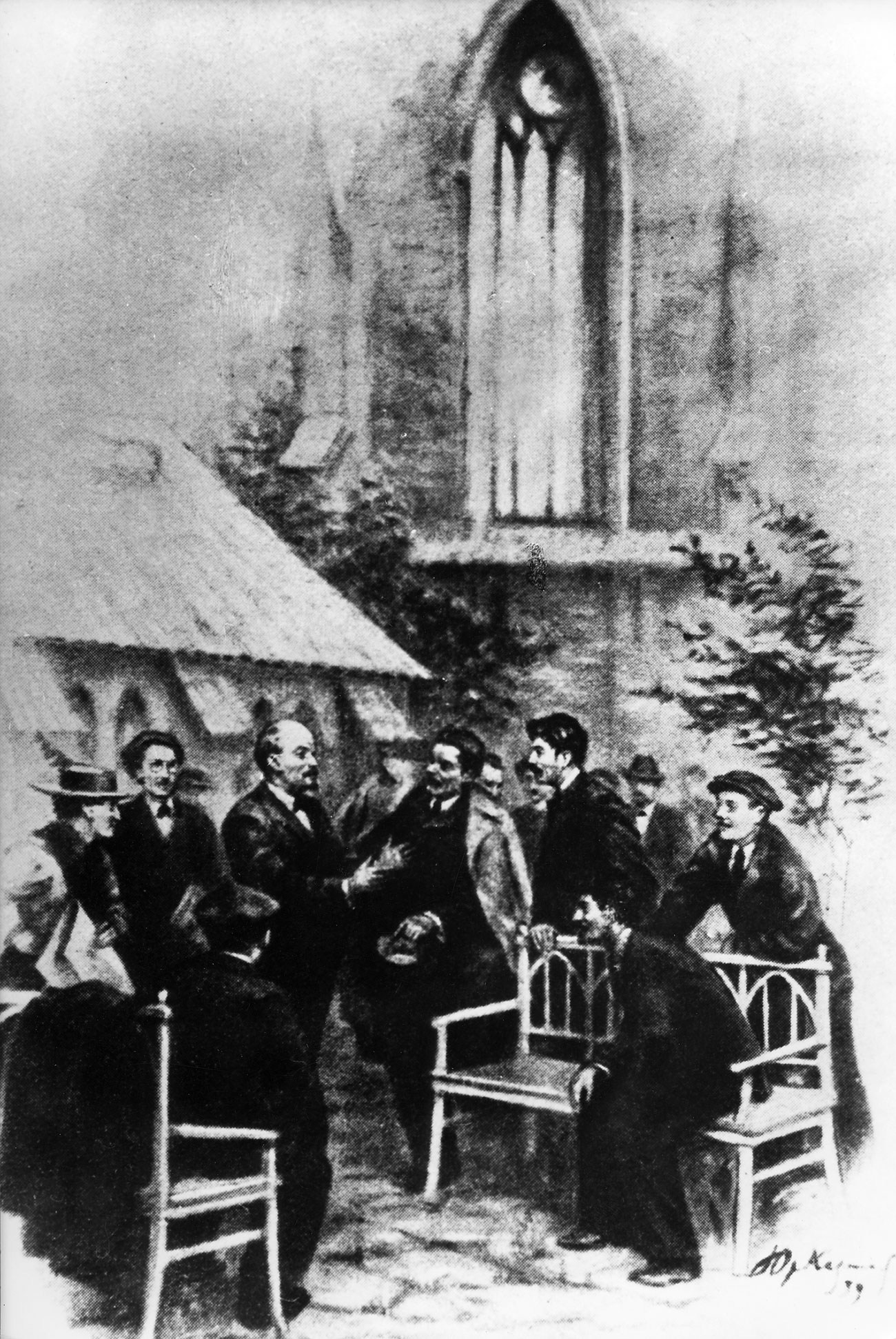

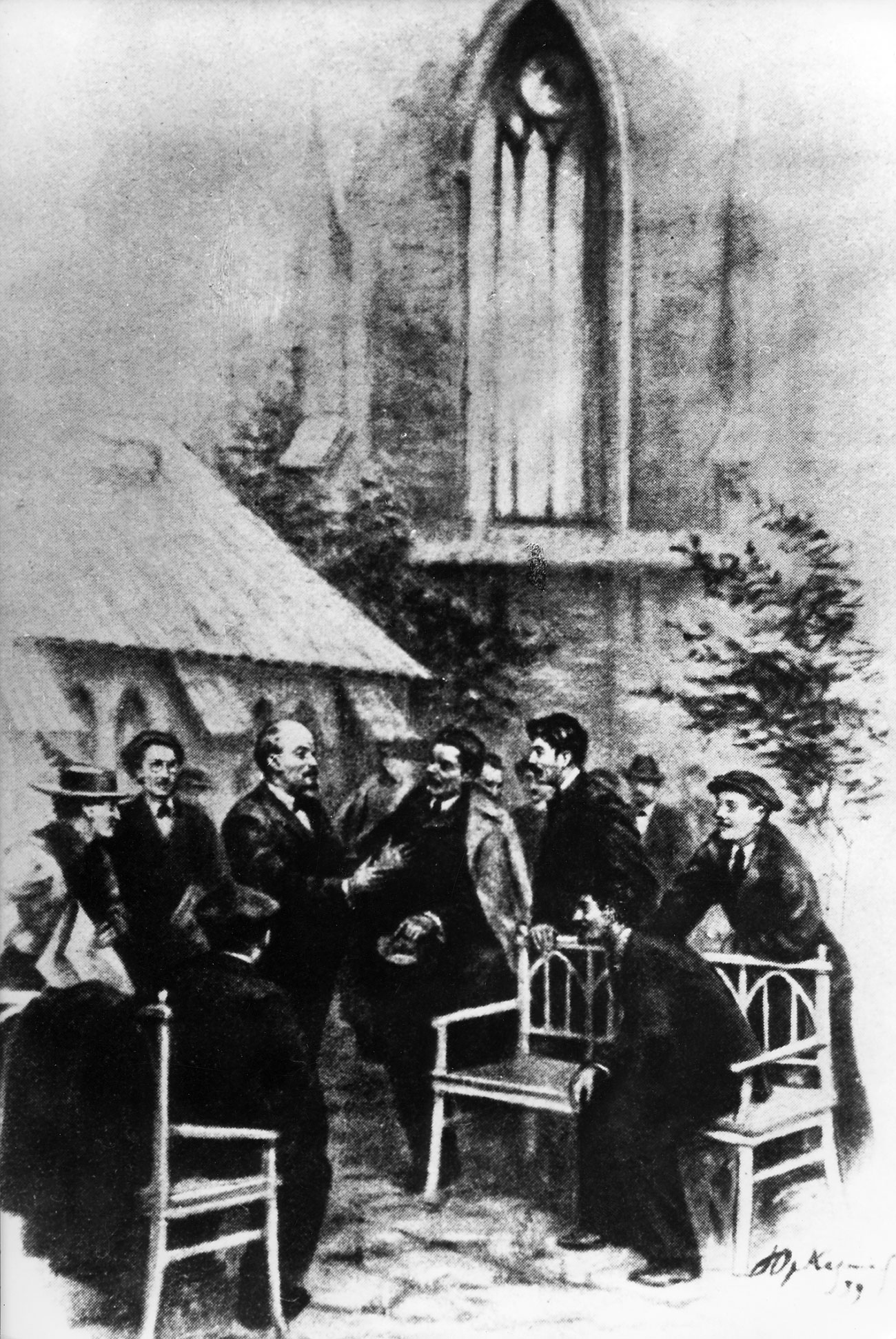

Vladimir Lenin talking to writer Maxim Gorky and Joseph Stalin at the Day of Social-Democratic Working Party of Russia in London, 1907. Drawing by Kamitshev.

Ullstein Bild Vladimir Lenin talking to writer Maxim Gorky and Joseph Stalin at the Day of Social-Democratic Working Party of Russia in London, 1907. Drawing by Kamitshev. Source: Ullstein Bild

Vladimir Lenin talking to writer Maxim Gorky and Joseph Stalin at the Day of Social-Democratic Working Party of Russia in London, 1907. Drawing by Kamitshev. Source: Ullstein Bild

The Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 inspired workers all over the European continent. In the aftermath of the First World War, strikes were held and workers’ councils formed from Germany to Hungary, to Italy and Britain. In Ireland, hundreds of councils were established — but the Limerick Soviet stood out above the rest.

In 1918, before the establishment of the soviet, about 15,000 workers taking part in the city’s May Day parade passed a resolution in solidarity with workers around the world. They declared “that we, the workers of Limerick, extend fraternal greetings to the workers of all countries, paying particular tribute to our Russian comrades who have waged such a magnificent struggle for their social and political emancipation.”

The trigger for more drastic action came nearly a year later with the arrest of Robert Byrne, a well-known trade unionist and member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). After his arrest, Byrne went on hunger strike and was moved to hospital. A rescue attempt by his IRA comrades and subsequent gun battle with the police ultimately led to his death — but it sparked events which had the potential to alter the course of history.

Robert Byrne. Source: open sources Robert Byrne. Source: open sources |

Thousands took to the streets for Byrne’s funeral. The British responded to this rebelliousness by declaring martial law in the city. Limerick was now a “special military area” and people were forced to obtain permits to travel within and around it. Those who lived and worked in different boroughs had to cross checkpoints to get where they were going — and anyone could be denied a permit. Unwilling to submit, the workers rose up and a general strike was called. Roughly 14,000 workers took part. In a city of 38,000 at the time; the effect was immediate.

A workers’ council was set up to keep the city running. The soviet rationed food, controlled prices and maintained law and order. No looting was reported. In fact, there was even a decrease in petty crime. When the workers ran out of money, they began printing their own currency. They also printed their own information bulletins. It was The Irish Times that first described the movement as a “soviet” — certainly not intending to be complimentary — but the workers proudly claimed the name.

One historian, Dr. O’Connor Lysaght, in his detailed and fascinating account of events, tells the amusing story of a U.S. army officer who visited Limerick and expressed surprise over how the city was being run. “Who rules in these parts?” he is reported to have said. “One has to get a military permit to get in, and be brought before the soviet to get a permit to leave.”

Source: Youtube / cobrolchain2

The Limerick Soviet would probably never have garnered as much attention as it did had it not been for a lucky coincidence. A bevy of journalists from all over the world were already in Limerick to cover a pilot’s attempt to fly across the Atlantic. As such, they had a front-row seat to the action.

But the Limerick Soviet was short-lived. For the British, allowing the workers to claim victory was never an option. The risk was too big that a victory in Limerick would spark a nationwide struggle.

Furthermore, trade unionists weren’t universally on board with the strike. Under pressure from the powerful Catholic Church, the British, business owners and the media, the strike was eventually called off on April 27. Workers applied for permits and returned to work.

Could Limerick ever have been Ireland’s Petrograd? Could the actions of the Limerick Soviet ever have led to a socialist revolution? There’s no consensus, but many socialists and communists saw those two weeks in April 1919 as a lost opportunity.

Vladimir Lenin wrote of the earlier Irish nationalist uprising against the British in 1916 that it was “the misfortune of the Irish that they rose prematurely, before the European revolt of the proletariat had had time to mature."

Likewise, in 1919 it was too soon for the Irish soviets. Still under the thumb of British rule, for most Irish, nationalism was the greater priority, not socialism or communism. The red flag was raised in other Irish cities and towns in the years to come, but a Workers’ Republic wasn’t on the cards.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox