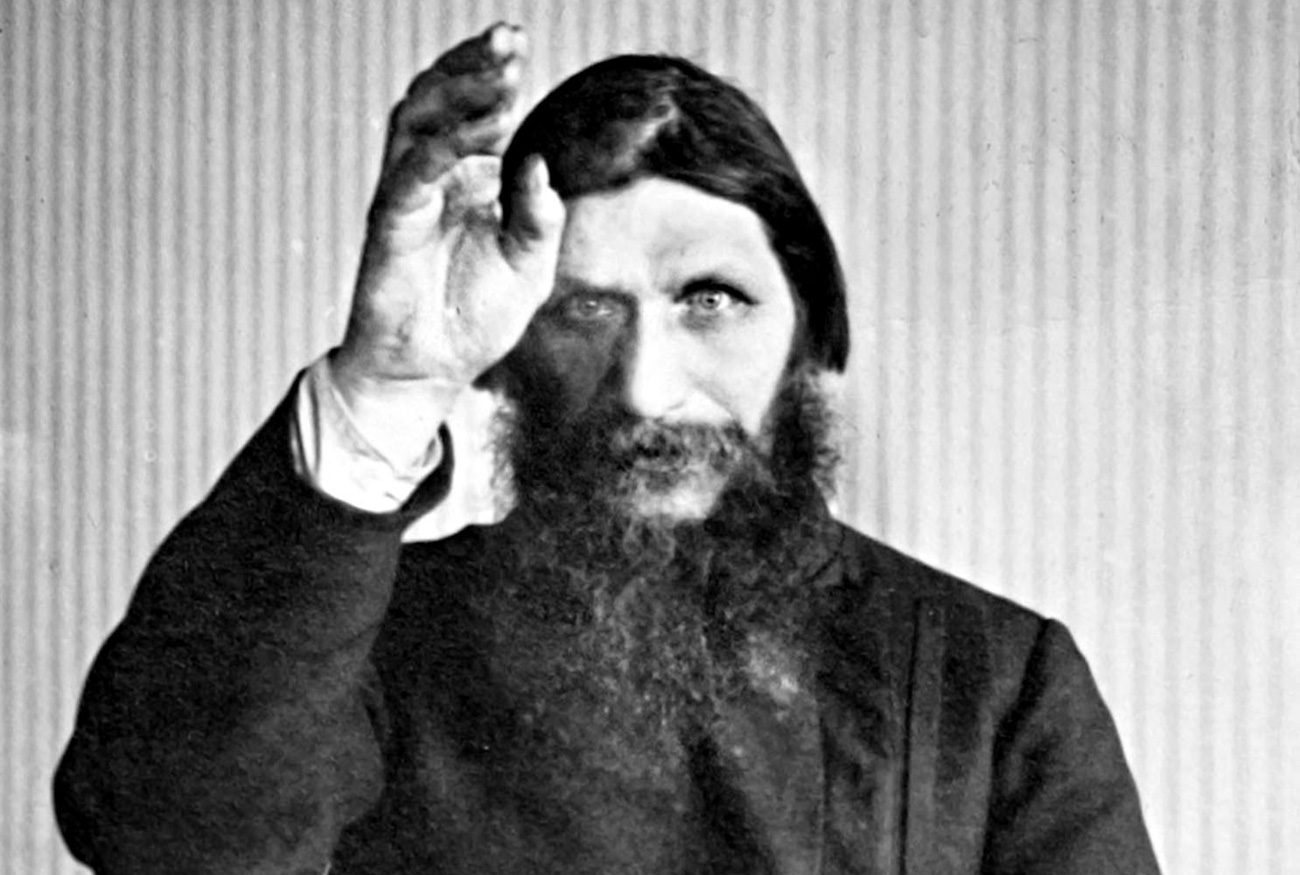

Grigory Rasputin.

Alamy/Legion MediaOn Dec. 17, 1916, which is Dec. 30 under the current calendar, “the streets of St. Petersburg had a celebratory air to them; elated passers-by hailed and greeted not just acquaintances but total strangers as well. … Thanksgiving services were held in churches across the city; in theaters, the public demanded that the national anthem be played and then ask for a repeat enthusiastically.” Anyone reading this description, part of a remembrance by Felix Yusupov, might assume people were celebrating a military victory. But instead, this was how citizens of the imperial capital reacted to the news that, on the previous night, a group of aristocrats had assassinated Grigory Rasputin.

By the time Rasputin, a native of Siberia’s Tyumen Region, arrived in the city in 1904 or 1905, he had already become known as a religious man who had undertaken pilgrimages to monasteries and holy sites. He was said to have magical abilities, including the ability to heal.

In St. Petersburg, Rasputin made the acquaintance of many influential members of the clergy, including Archbishop Theophan of Poltava, who was a spiritual advisor to the royal family. Theophan reportedly introduced Rasputin to Emperor Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra. Rasputin made a favorable impression on both church elders and St. Petersburg society mavens.

Makarij, Theophan of Poltava and Rasputin, 1909. / Source: Archive photo

Makarij, Theophan of Poltava and Rasputin, 1909. / Source: Archive photo

Metropolitan Veniamin, an associate of the archbishop, later recalled: “Father Theophan was entirely consumed by the incomer, seeing in him a 'servant of God' and a 'holy man.’”

Veniamin himself also initially liked Rasputin: “Rasputin impressed me immediately, both by his unusually intense personality […] and by his acute understanding of people's souls…”

According to historian Georgy Mitrofanov, “Rasputin was not an opportunist; he was indeed bestowed with a special outlook and special spiritual qualities.”

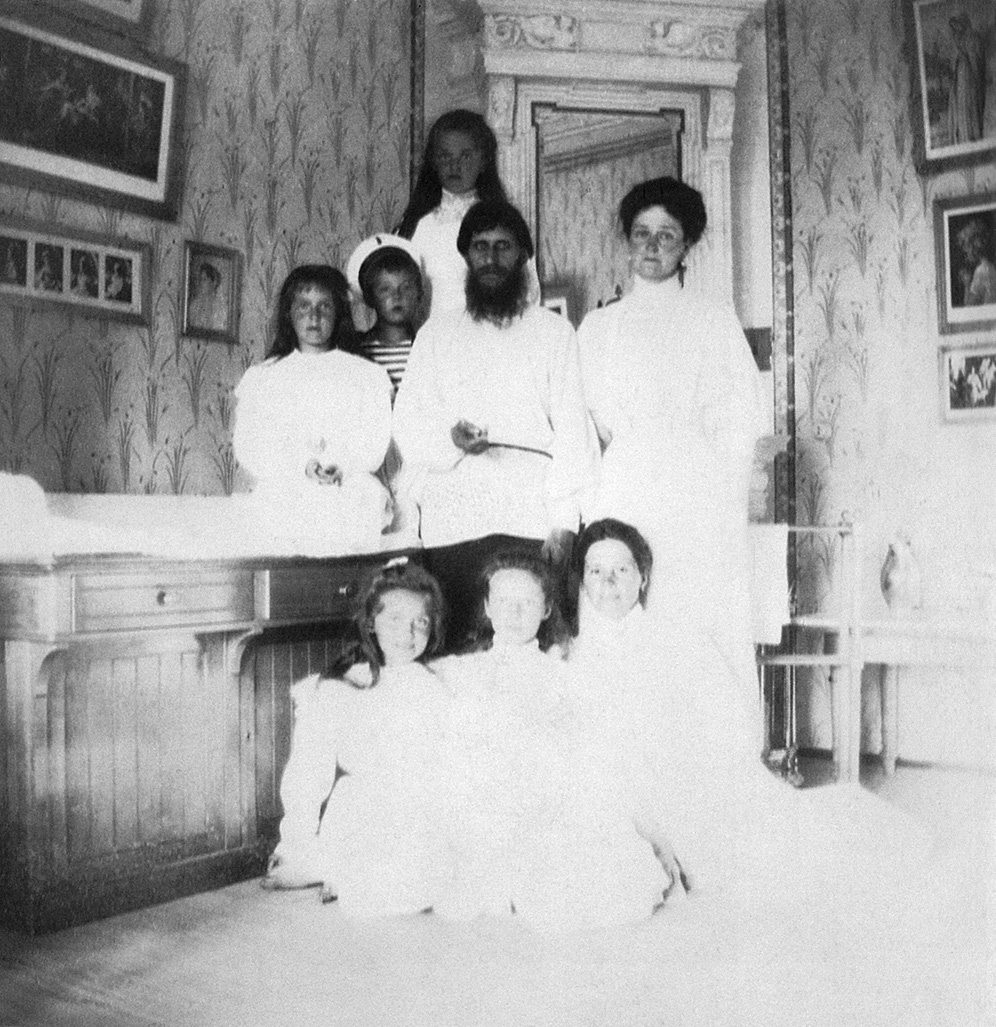

Once he became part of the circles surrounding the royal family, Rasputin endeared himself in particular to the empress. Alexandra held out hope that Rasputin may be able to help her son Alexei, the heir to the throne, who suffered from hemophilia.

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with Rasputin, her children and a governess, 1908. / Source: Archive photo

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with Rasputin, her children and a governess, 1908. / Source: Archive photo

According to numerous eyewitness accounts, whenever doctors were unable to help the child, Rasputin would come to the rescue. In his book, The Last Grand Duchess, Ian Vorres noted that Nicholas II’s younger sister Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna said Rasputin's interventions had indeed been helpful. Olga’s opinion is especially important here as she was known to have disliked Rasputin.

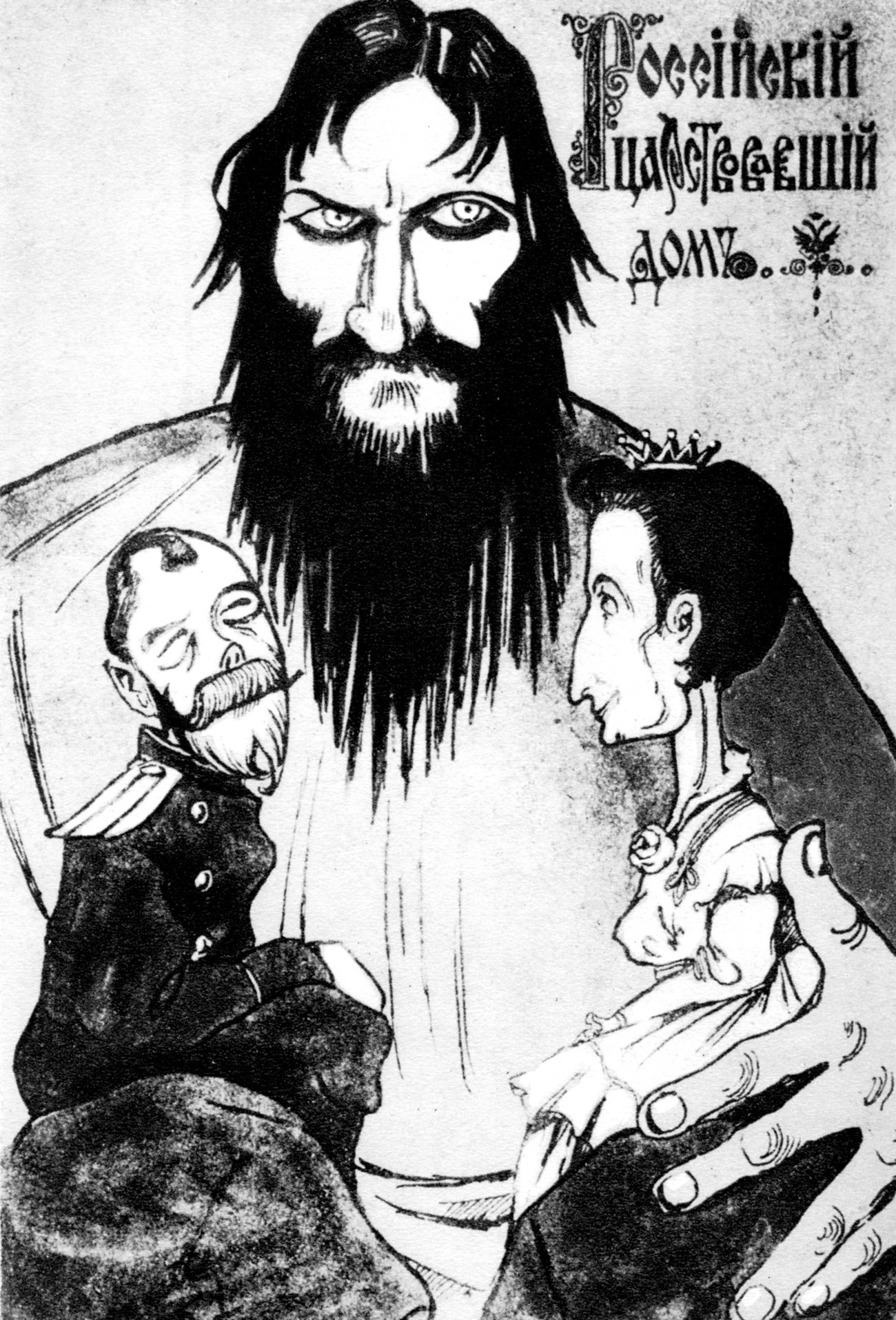

Eventually his relationship with the royal family went to Rasputin's head. Historian and literary critic Alexei Varlamov wrote in his book Grigory Rasputin-Novy that Rasputin started bragging about his royal connections and trading on his ties to receive benefits from those who wanted access to the tsar. He received a spacious apartment in central St. Petersburg, in which he received petitioners. Rasputin did try to accommodate their pleas. He doled out money to his visitors and in some cases he would call a member of the government on behalf of the petitioner.

Russian clergyman, caricature on his influence on the imperial family. / Source: Alamy/Legion Media

Russian clergyman, caricature on his influence on the imperial family. / Source: Alamy/Legion Media

By 1910, however, Rasputin was no longer considered a righteous person. He was known for binge drinking, debauchery and womanizing. When confronted about the later charge, Rasputin said that women were naturally drawn to him, and that only through sin could one could receive grace.

Rasputin’s reputation as a womanizer extended even to the empress. One of Alexandra’s actual letters to Rasputin read: “Only then is my soul at rest when you, my teacher, is sitting beside me and I am kissing your hands and leaning on your savory shoulders.” The letter was published in mimeographed form in late 1911. Vladimir Kokovtsev, the country's prime minister at the time, said that the letters gave “food for very revolting gossip,” although he personally thought of them as being, “in essence, a manifestation of [the empress's] mystical attitudes.”

Rasputin and his admirers, 1914. / Source: Archive photo

Rasputin and his admirers, 1914. / Source: Archive photo

The letters were reportedly leaked by Hieromonk Iliodor, a former follower of Rasputin who became one of his bitterest enemies. Iliodor published a book about Rasputin, entitled Holy Devil. The monarchy's public image had been dealt a serious blow.

Despite the continuing scandals, Rasputin’s influence continued to grow. Several ministers, including the newly appointed prime minister Boris Shtrumer, owed their appointments to the “mad monk.”

After Russian entered World War I, however, Rasputin and the royal family faced additional scrutiny. Rumors began to circulate that the country’s military defeats were due to the empress’s German blood. The word treason began to be mentioned in the same sentence with Rasputin's name. Varlamov wrote that during his last months, Rasputin was drinking particularly heavily, as if sensing both his death and that of the royal family.

Prince Felix Yusupov. / Source: RIA Novosti

Prince Felix Yusupov. / Source: RIA Novosti

The end came on Dec. 16, in the house of Prince Felix Yusupov, a relative of the Romanovs, who had developed a plot aimed at saving the royal family's reputation. According to Yusupov’s remembrance of the event, a group including Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Duma deputy Vladimir Purishkevich and himself first fed Rasputin some poisoned candy, shot him several times and finally threw his body into a hole cut into the ice in a canal.

Two months after Rasputin's death, Nicholas II abdicated. The former emperor and his family were first sent to Siberia, then moved to Yekaterinburg. There they were subsequently executed along with their servants in the basement of a house in the Urals city. A total of 57 icons were found among the Romanovs' possessions after their deaths — three of them gifts from Rasputin.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox