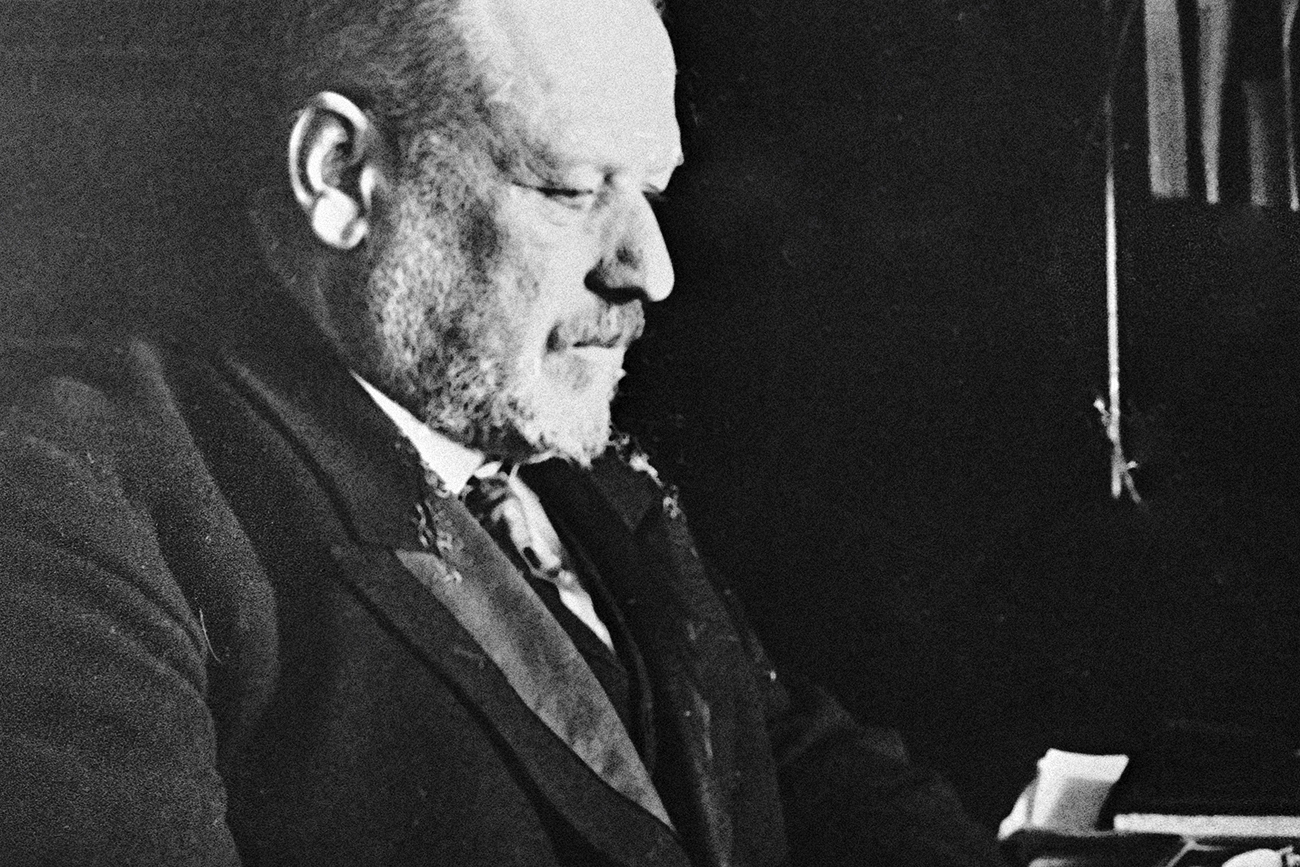

Mikhail Rodzianko, Dec. 9, 1916.

RIA NovostiRodzianko, a wealthy landowner, whose estates were located in what is today eastern Ukraine, became a notable Russian politician several years before World War I when he was elected Chairman of the State Duma. He saw himself as a mediator between society and the tsar and aimed to obtain Nicholas II's approval on the formation of a government that would be responsible to parliament. Otherwise, he warned the tsar, there would be a revolution.

However, the monarch believed that serious political reforms were inappropriate, given the fact that Russia had entered the war in 1914. He did not want to share power with the State Duma, which he had been forced to summon after the first Russian Revolution of 1905-1907.

With the tsar's intransigence, the crisis in food supplies and the fall of the monarchy's prestige people in the capital began speaking of a conspiracy against the emperor. The talks became particularly resonant after the murder of Grigory Rasputin, who was close to the tsar's family. The violent death of the omnipotent favorite brought joy to the educated classes in Petrograd, but did not please Rodzianko. He thought that this signaled the beginning of the end of the Romanov Empire.

Rodzianko, being an inveterate monarchist, preferred to maintain a distance from talk about a palace coup.

Later he would remember that shortly before the revolution, early in 1917, one of the generals came to the capital from the front and told members of parliament that, "A coup is inevitable and they feel it at the front. If you decide to carry out this extreme measure, we will support you."

"You do not understand what will happen after the tsar's abdication… I will never attempt a coup… I took an oath…" replied the State Duma chairman. Two and a half weeks before the revolution, on February 10, Rodzianko held his last audience with Nicholas II, in which he warned the tsar that the country was in danger and that a revolution was possible. "The information I have is completely contradictory," Nicholas replied.

Rodzianko remained faithful to the course he had chosen even during the revolution. In the climax of the uprising - Feb. 26-27, when Petrograd residents demanded the end to autocracy - he sent two telegrams to the tsar, who was at the front, stating: "There is anarchy in the capital. The government is paralyzed… Some military units are firing at each other."

He called on the emperor to "immediately order an individual who is trusted by the people to form a new government… Any delay is equal to death."

The tsar's response characterizes his attitude towards the State Duma chairman and his perception of the situation in the country: "Once again that fatso Rodzianko wrote me some nonsense, which I will not even respond to."

Instead of forming a "responsibility ministry," the tsar dissolved the Duma. Rodzianko's secretary later remembered how the Duma chairman was saddened by the tsar's decision. Learning about the decision, he got on his knees and prayed before an icon, repeating: "Everything is finished… Everything is finished!"

In most descriptions of the February Revolution, Rodzianko and the Duma in general are portrayed as passive observers. However, some believe that Rodzianko and the parliamentarians played a bigger role, practically managing the revolt. St. Petersburg historian Andrei Nikolaev notes that on February 27 Rodzianko convened the Council of the Elders of the Russian Parliament. Violating Nicholas II's decree, the council adopted a resolution saying that the State Duma deputies should not break up. The document also mentioned that the "new slogan of the moment is the abolition of the old government." Headed by the speaker, the Duma practically began the overthrow of the tsarist regime.

For several days Rodzianko led the country, having become president of the Provisional Committee of the State Duma, which took power during the uprising. He qualified for the post of prime minister of the Provisional Government, but his colleagues preferred Count Lvov.

After the Bolsheviks came to power Rodzianko fled to the Whites. Their defeat in the Russian Civil War forced him to flee the country. He settled in Serbia, but was not popular among Russian émigrés. Later, as an elderly man he was cruelly beaten up by monarchist thugs. They thought that he was responsible for the destruction of the tsarist regime in Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox