Reproduction of 'Portrait of Inessa Armand' by A.Lurye.

Mikhail Filimonov/RIA NovostiVladimir Lenin, founder of the Soviet Union, can hardly be accused of excessive sentimentality. Throughout his life he easily parted ways even with his closest friends when their political views ran counter to those of his own; and after seizing power, he executed adversaries remorselessly.

One of the few instances when this energetic politician publicly demonstrated a weakness came on October 12, 1920, the day when Inessa Armand, his long-lasting comrade, personal friend, and lover, was laid to rest.

“As we were following the coffin, Lenin was barely recognizable,” recalled revolutionary activist Alexandra Kollantai. “He was walking with his eyes shut tight, and was hardly standing on his feet.”

Several weeks earlier, Armand died suddenly of cholera in Nalchik (a town 850 miles south of Moscow), which came as a hard blow to Lenin.

“I fear lest Inessa's death should do Volodya [Lenin] in," his wife Krupskaya wrote. “He has been crying, and his gaze is miles away.”

A French-born socialist, Inessa Armand found herself in Moscow at age 15, following the death of her father. She was brought up in Russia by her grandmother and aunt, and by the age of 35, she had been married twice. Her second husband was Vladimir Armand, who “infected” her with revolutionary views.

Inessa Armand, 1895. / Photo: TASS

Inessa Armand, 1895. / Photo: TASS

In 1904, Inessa joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, and for her activities in the 1905 revolution she was exiled to the north of Russia, from where she fled to Switzerland in 1908.

When Armand's second husband died of tuberculosis the mother of five found herself alone but nevertheless continued to participate in the revolutionary movement. She maintained close contacts with other French socialists, translated revolutionary literature, and completed a degree in economics. Bolshevik comrades spoke warmly of Armand.

“She stood out for her neglect of creature comforts, her attention to comrades, and her readiness to share her last portion of bread with them,” revolutionary activist Lyudmila Stal recalled.

Many contemporaries highlighted Armand's love of life, the happiness she would bring by her presence, as well as her natural beauty and charm.

Armand's fateful first meeting with Lenin happened in 1909. In fact, thanks to his writings she became a socialist. For a number of years the two were living and working in Paris, and many contemporaries suggested that their relationship had grown into something bigger than friendship during that period.

Inessa Armand, 1909. / Photo: TASS

Inessa Armand, 1909. / Photo: TASS

“Lenin could not take his Mongolian eyes off this small Frenchwoman,” French socialist Charles Rappoport noted. In his letters to Armand, Lenin would address her as “my dear friend”, and otherwise manifested his extreme care and fondness.

“Almost all of my activity here in Paris was linked to my thoughts of you with a thousand threads,” Armand would write to Lenin several years afterward, in 1913.

The letter makes it clear that Armand was utterly in love with her comrade and teacher: “I so much loved to not just listen to you but also look at you speaking. First, your face becomes so lively when you speak; second, observing you at such moments was very convenient because you did not notice my glances...”

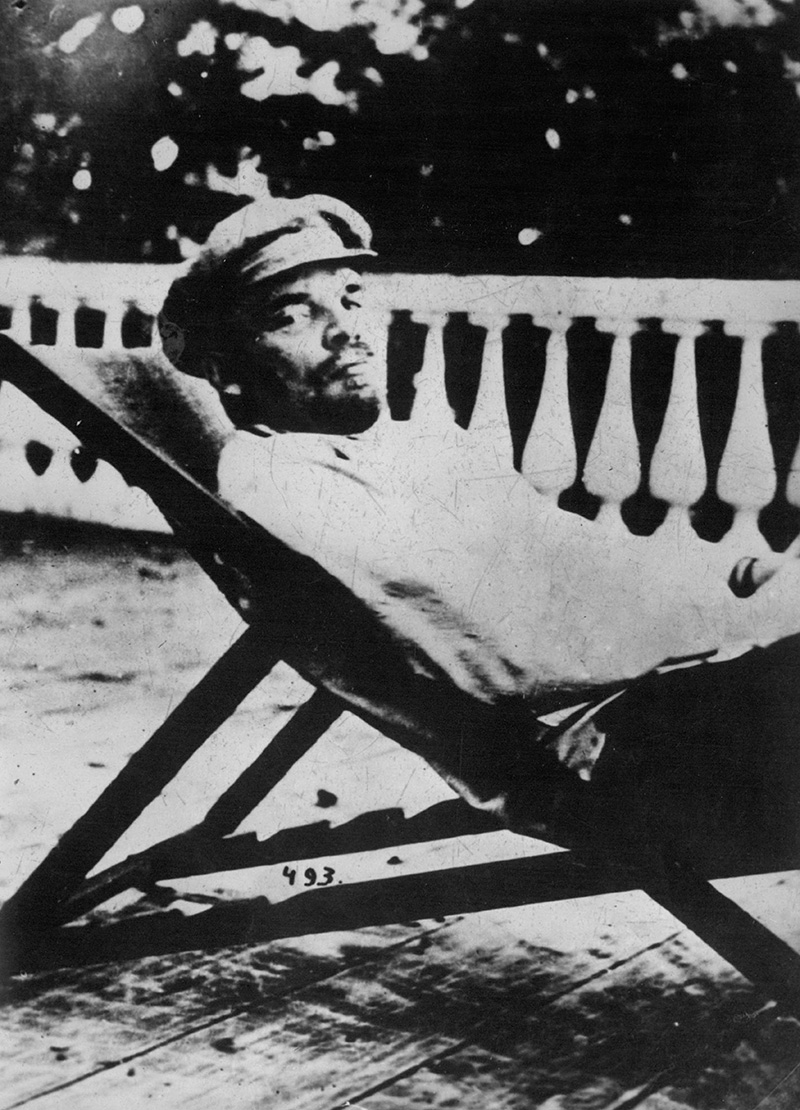

Vladimir Lenin relaxes in sauna outside on deck in sun, 1918. / Photo: ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

Vladimir Lenin relaxes in sauna outside on deck in sun, 1918. / Photo: ZUMA Press/Global Look Press

By the time he met Armand, Lenin had been married to Nadezhda Krupskaya for 11 years. Apart from being a devout revolutionary and Lenin's trusted assistant, Krupskaya was also his faithful spouse. Despite the natural rivalry for the affection of the Bolshevik leader, the two women managed to establish a friendship.

Krupskaya wrote: “It would get cozier and more fun every time Inessa came.” Armand, for her part, had this to say about Krupskaya: “I liked her virtually on our first meeting. She emits this special kind of tenderness towards comrades.”

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife. / Photo: RIA Novosti

Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's wife. / Photo: RIA Novosti

Lev Danilkin, the author of a recently published biographical work on Lenin, notes that there is no documentary evidence of an amorous link between Lenin and Armand; only the conjecture and gossip of contemporaries. He surmises that Lenin's relations with Armand and Krupskaya may have followed the new socialist moral concept proposed by Nikolay Chernyshevsky in his novel What is to be done: “Essentially, everything is allowed as long as it is based on mutual respect.”

This is why Danilkin believes that both Krupskaya and Armand managed to overcome any potential jealousy. They were like-minded persons who respected each other and had similar ideals that were radical for their era.

Whatever it was, the relationship between Lenin and Armand did not last long. The revolutionary leader eventually opted for fidelity to his wife with whom he had lived many years. In a letter from 1913, Inessa wrote with visible pain: “We have parted, my dear!”

Lenin with his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya at Gorky, 1922. / Photo: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

Lenin with his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya at Gorky, 1922. / Photo: Mary Evans Pictrure Library/Global Look Press

Armand remained true to Lenin and the revolution to the end of her life. Despite her French citizenship, which entitled her to a comfortable life in Europe, she joined Lenin and Krupskaya in their return to Russia in 1917.

Armand took part in the October Revolution and continued to support the fledgling Soviet Union while living in a decrepit cold apartment, Danilkin said. She eventually succumbed to cholera at age 46. Ironically, she contracted the disease during a holiday at a resort in the south.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox