State Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting of the USSR Chairman Sergey Lapin during a TV management meeting, 1973 / Lev Nosov/RIA Novosti

State Committee for Television and Radio Broadcasting of the USSR Chairman Sergey Lapin during a TV management meeting, 1973 / Lev Nosov/RIA Novosti

The Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917 while championing freedom, yet one of their first decisions was to limit free speech through harsh censorship. In early November 1917, the Soviet government signed the Decree on Press which prohibited publishing any “bourgeois” articles criticizing the Bolsheviks’ authority.

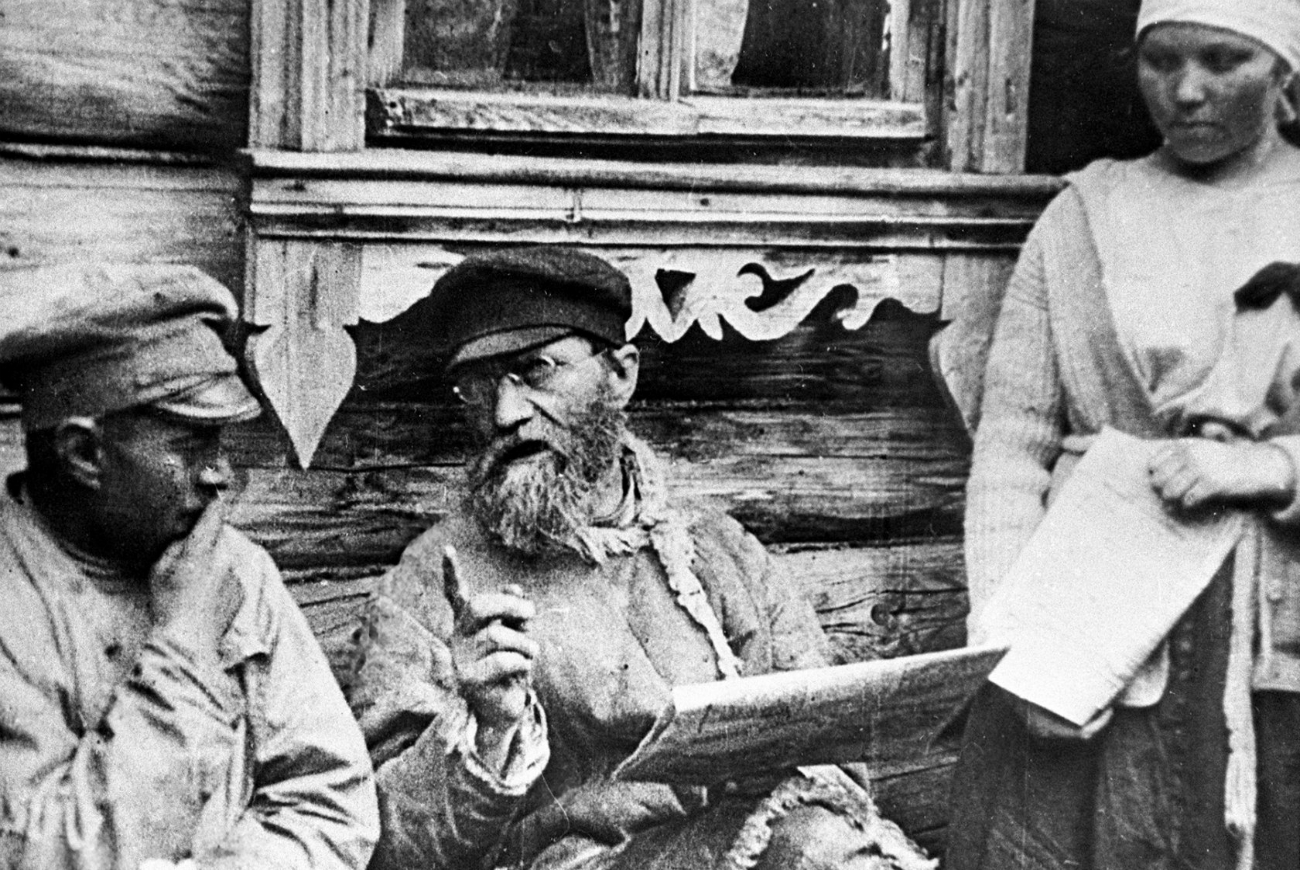

Peasants reading a newspaper which published Lenin's decrees on land and on peace, 1918. / RIA Novosti

Peasants reading a newspaper which published Lenin's decrees on land and on peace, 1918. / RIA Novosti

As the years passed political censorship grew stronger, reaching its peak under Joseph Stalin’s reign. After his death the state relaxed its stance but censorship remained until Mikhail Gorbachev declared glasnost in the late 1980s.

As the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (GSE) puts it, Soviet censorship had “a different character than the one existing in bourgeois states and aimed only at protecting the interests of the working class.” This is a bold statement, especially given the fact the Soviet elite employed censorship for its own bloody gain, most notably during Stalin’s Great Purge.

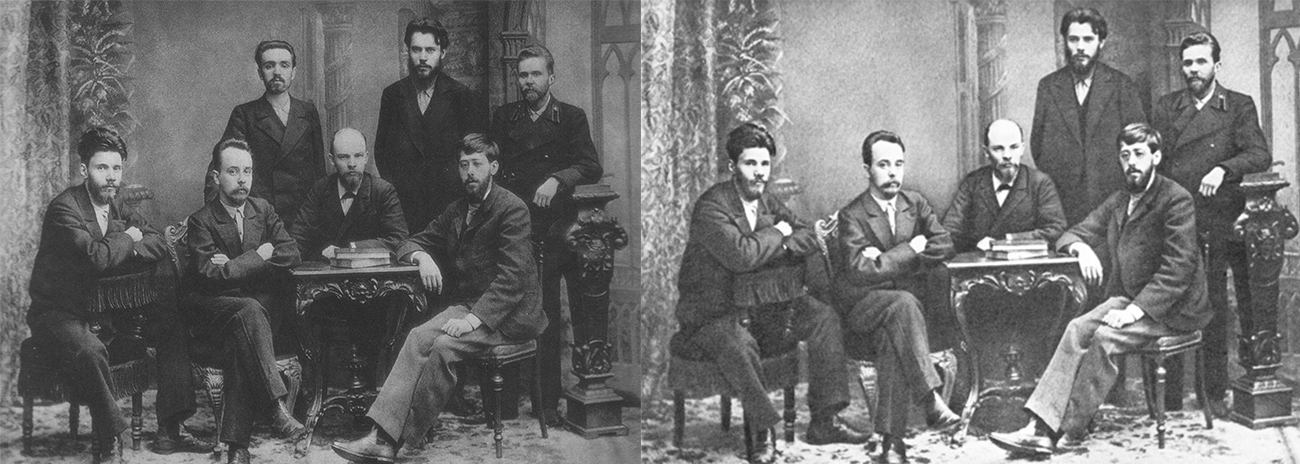

A meeting of the St. Petersburg chapter of the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class in February 1897. Shortly after the picture was taken the whole group was arrested. / Nadezhda Krupskaya

A meeting of the St. Petersburg chapter of the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class in February 1897. Shortly after the picture was taken the whole group was arrested. / Nadezhda Krupskaya

“The physical eradication of Stalin's political opponents was followed by their obliteration from all forms of pictorial existence,” British historian David King wrote in his book The Commissar Vanishes. Retouchers worked hard erasing traces of fallen leaders from all photographs and images. For instance, Nikolay Yezhov, an infamous chief of the NKVD (secret police organization, the predecessor of the KGB) who masterminded the mass political repressions in 1936-1938, fell out with Stalin and found himself in the hands of the secret police in 1940, before being executed. After that Yezhov disappeared from all photographs with Stalin.

The same happened to another notorious NKVD chief - Lavrentiy Beria. One of Stalin’s most trusted allies, he was left high and dry after his patron’s demise in 1953 and was also executed. This was followed by an insistent government request that all people who owned a GSE containing an article about Beria must replace it with a revised version, which had no mention of the ill-fated official.

In 1921, the young Soviet government created the Glavlit (General Directorate for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press) which for decades remained the main instrument of controlling literature. Glavlit’s censors decided if a book was published in the USSR, or if it was banned.

As a result, Soviet citizens could not read many books, some of which are now regarded as classics - including Mikhail Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita and Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, not to mention most works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn that criticized the Soviet regime. The circulation of books written by émigré writers who had fled Soviet Russia were, of course, prohibited - robbing the public of Ivan Bunin and Vladimir Nabokov’s novels, to name just two authors.

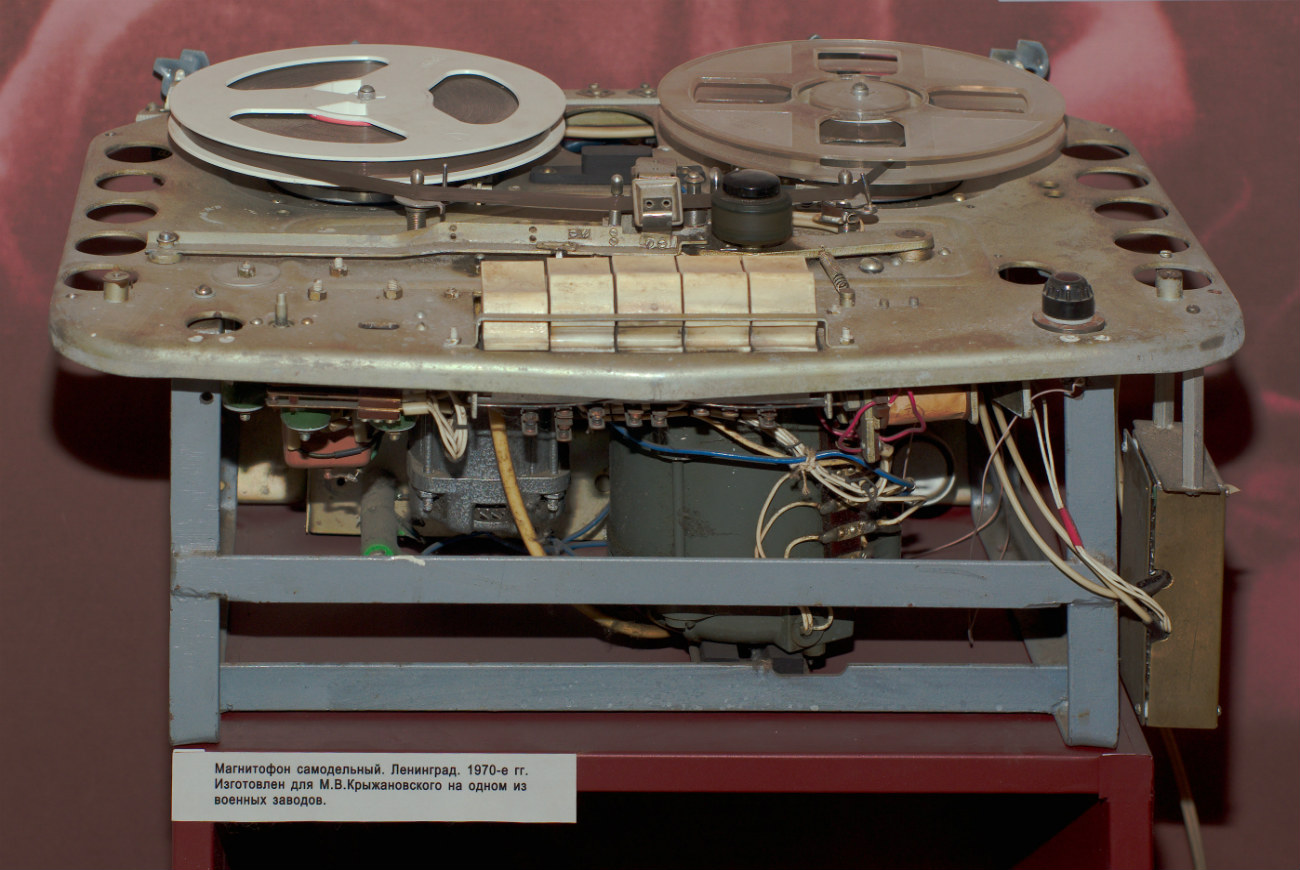

Tape recorder «Tembr» MAG-59M, 1964 (attributed as «self-made»). / State museum of political history of Russia

Tape recorder «Tembr» MAG-59M, 1964 (attributed as «self-made»). / State museum of political history of Russia

Nevertheless, the Soviet government wasn’t able to completely eradicate literature it deemed “dangerous.” Through the ages, people opposing censorship have circulated handmade copies of banned literature. In the Soviet Union, this was called samizdat (self-published) and scores of illegal books were enjoyed by readers as a result.

Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the USSR from 1953 to 1964, was more liberal than Stalin, whose repressive policies he condemned in his secret speech in 1956. According to the Russian historian Leonid Katsva, Khrushchev even thought of abolishing ideological censorship in art, but changed his mind.

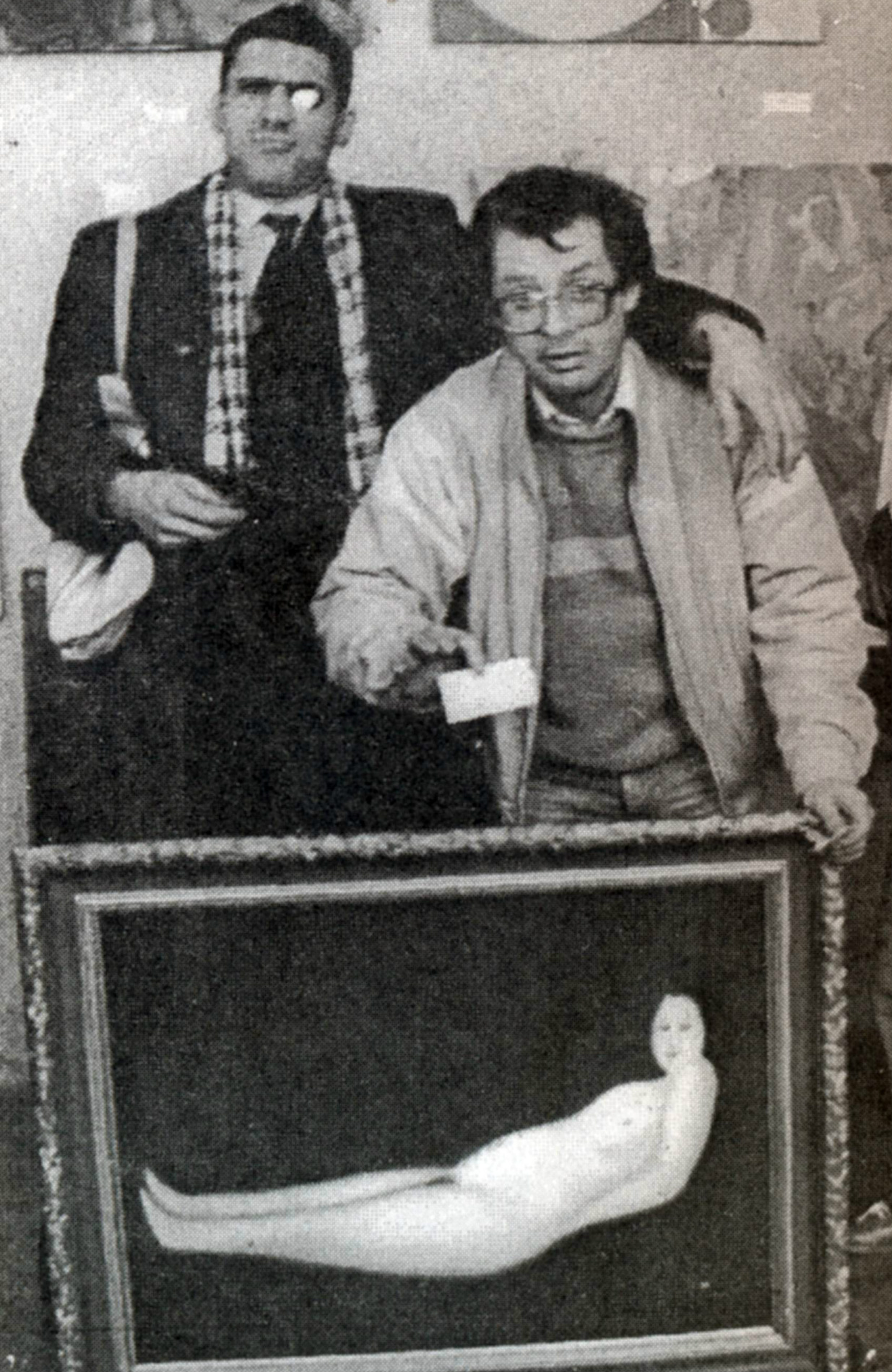

Artists Avdey Ter-Oganyan and Yuri Palaichev with his 'New Nude', Taganrog, 1988. / Avdey Ter-Oganyan's archive

Artists Avdey Ter-Oganyan and Yuri Palaichev with his 'New Nude', Taganrog, 1988. / Avdey Ter-Oganyan's archive

One of the factors that influenced Khruschev’s decision was his encounter with the avant-garde. After witnessing the “New Reality” exhibition performed by young artists, Khrushchev became very angry with their unrealistic style of painting and started shouting: “Soviet people don’t need all this! We declare war on you!”

Under the rule of Leonid Brezhnev (1964 to 1982) the state continued to oppress artists working outside the realm of social realism. For example, in 1974 the government demolished an unofficial avant-garde exhibition in the suburbs of Moscow using bulldozers and water cannons. The event became known as the “Bulldozer Exhibition.”

Throughout the Cold War both the West and the USSR were trying to influence each other’s population by providing “alternative points of view.” In 1946, the BBC started broadcasting radio services for Soviet citizens. Voice of America, Radio Liberty, and Deutsche Welle all followed suit a couple of years later.

Unsurprisingly, the Kremlin was not happy with Western media trying to meddle with Soviet citizens so it started blocking radio frequencies used by foreign stations. According to Rimantas Pleikis, a radio journalist from Lithuania, the USSR possessed the most powerful and wide scale “anti-radio” system in the world.

But even that system had cracks. Those who wanted to continue tuning in to the “foreign voices” and alternative opinions - along with jazz and rock music - found a way. Finally, in 1988 Mikhail Gorbachev officially stopped blocking Western radio stations.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox