Some believe Ivan hid the collection somewhere in Moscow or another Russian city.

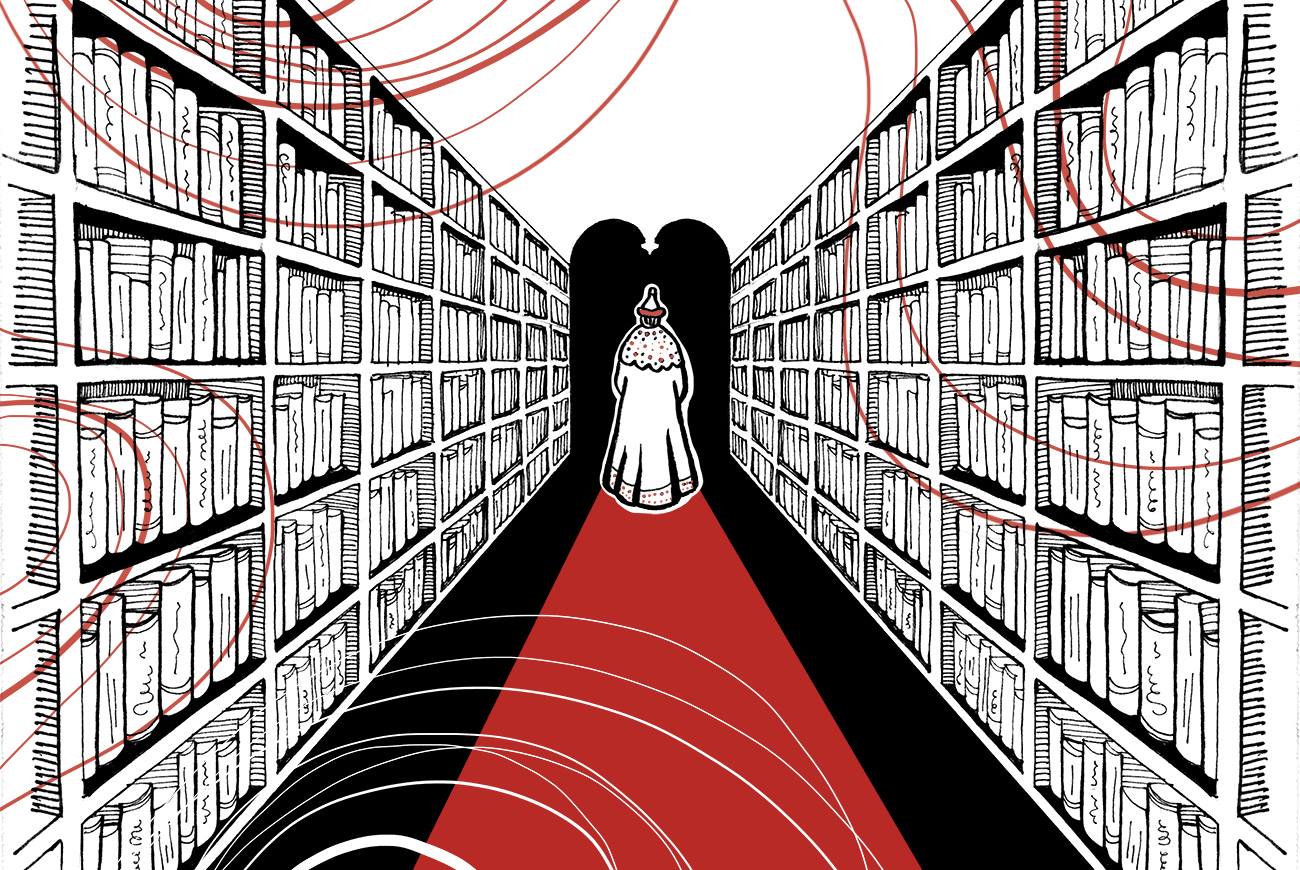

Varvara GrankovaThis story began ages ago. In the 15th century the Turks conquered Constantinople and toppled the all powerful Byzantine Empire. Many Greeks of the Orthodox faith fled and Thomas Palaeologus, brother of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI, was among them. He took refuge in Rome, but not before (if legend is to be believed) packing up the library added to by each Byzantine emperor and taking it with him.

The library contained around 800 books, including unique masterpieces of Greek and Roman literature. They were inherited by Thomas’s daughter Sophia Palaiologina who left Rome for Russia and wedded Ivan III, the Grand Prince of Moscow. It was Sofia who brought the library to Russia but the collection became well-known as the “library of Ivan the Terrible (Ivan IV).”

The tsar with a brutal reputation, Sofia’s grandson, not only inherited the library (also known as “Libereya” from liber – “book” in Latin) but expanded it by sending his men all over Europe to collect rare folios and manuscripts. Some believe Ivan hid the collection somewhere in Moscow or another Russian city. After his death in 1584, the library disappeared without a trace.

At least, this is what legend tells us. Christopher von Dabelov, a 19th century historian from Derpt (now Tartu, Estonia) claimed to have seen a list of folios from the missing collection. Such a find would be the equivalent of unearthing the Holy Grail, but for bookworms, and the list allegedly included 142 volumes of Titus Livius’ History of Rome (historians are currently only familiar with 35 of them), a full version of Cicero’s De re publica (only fragments were preserved in Western libraries), and an unknown poem by Virgil…to name but a few of the manuscripts Libereya apparently contained.

On the other hand, many specialists remain skeptical about the library’s existence. Alexander Filyushkin, an associate professor of Russian history at the St. Petersburg State University, told Komsomolskaya Pravda why he doubts the legend.

First, he said, it’s very unlikely that Thomas Paleologus’ family who fled to Rome did not sell at least part of Libereya to raise funds. Secondly, he says all sources relating to the library cannot be fully trusted. For example, von Dabelov - who bragged about finding the list - failed to show the document to anyone.

Some European chronicles from the 16th to 18th centuries mentioned the legendary library, but it always sounds more like a myth with no solid proof, Filyushkin believes.

Even if the library of Ivan the Terrible had existed it could have easily been destroyed, specialists suppose. Moscow survived three huge fires during the 16th and 17th centuries (1547, 1571, and 1626) which could have burnt a hidden library to a crisp. Another theory is more far-fetched: The Poles who invaded Russia at the beginning of 17th century ran out of food after being besieged in Moscow’s Kremlin, so ate the leather covers of the folios and destroyed what remained.

Nevertheless, the skepticism hasn’t stopped enthusiasts from excavating the Russian capital in the hope of chancing upon the Czar’s literary treasure. People have also searched in vain outside Moscow - for example, Ivan’s beloved city of Vologda (465 km north of Moscow) and the Alexandrov Kremlin (121 km north-east of Moscow) where Ivan lived from 1565 to 1584.

And of course, many suspect the Moscow Kremlin is hiding Libereya.

Archeologists and adventurers have examined countless locations throughout the years: 19th century emperors and even Joseph Stalin let scientists into the Kremlin, hoping that they would find the priceless Byzantium books, but to no avail.

“If someone found the library they would be as famous as Yuri Gagarin” Filyushkin believes. Despite the unlikelihood Libereya exists, it remains a popular myth. As Alexander Vexler, an archeologist from Moscow, joked in an interview, “Of course the library of Ivan the Terrible exists. How can it not exist if it's been feeding journalists with material to write about for so long?”

This article is part of the

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox