A communist supporter holds a portrait of Joseph Stalin.

ReutersIn the early 1990s I was dealing much with statistics related to the Soviet terror. According to my calculations, during the whole period of the Soviet regime the security services arrested 7.1 million people. However, Russian public opinion believed that in 1937-1939 alone about 12 million people had been arrested. So, I put all my calculations aside. For a long time.

The above story was told by Memorial chairman, Arseny Roginsky. Memorial is a historical and civil rights organization that aims “to promote the revelation of the truth about the historical past and perpetuate the memory of the victims of political repression.”

As one of Memorial’s founders, Roginsky undoubtedly has done much for the gathering and disseminating of information about victims of political persecution in the USSR.

At the same time, as his account testifies, the popularly believed estimates of the number of Stalin’s victims in the late 1980s and early 1990s were suspect. The atmosphere in society was so emotional that even a respected historian did not want to publish controversial findings, even if they were well researched and based on fact. If one looks at the purported number of Stalin’s victims that were circulated at that time, it’s clear why Roginsky was not eager to go public with his data.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the famous dissident whose book, Gulag Archipelago, was popular during Gorbachev’s perestroika, was one of the most influential people on this issue. In that book he mentions 66.7 million victims of the Soviet regime from 1917 to 1959.

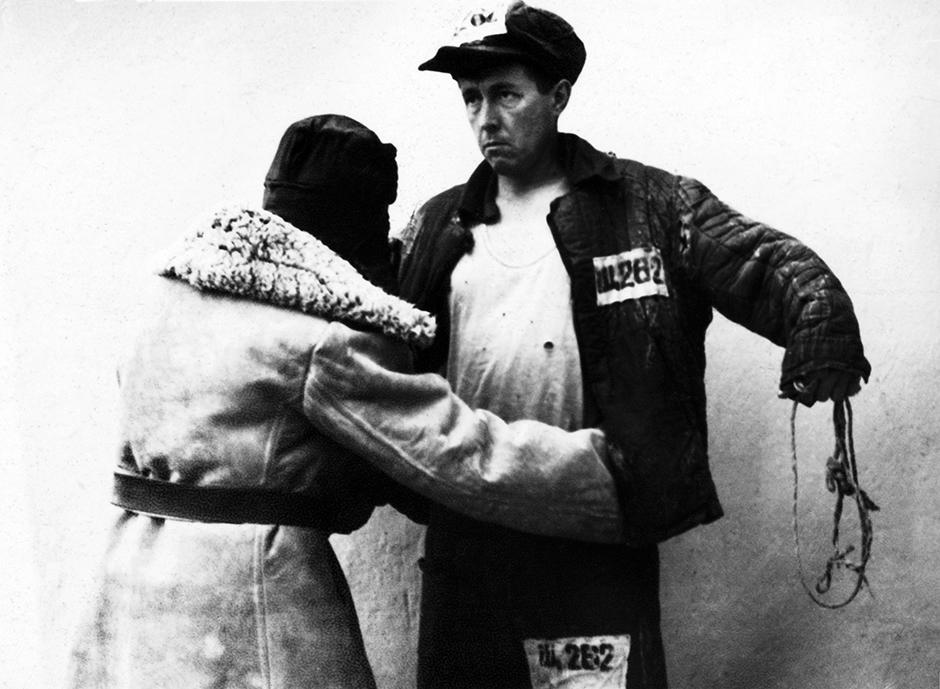

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in a quilted camp jacket just after being discharged. Kok-Terek, Kazakhstan, March 1953. In 1945 Solzhenitsyn was sentenced to 8 years in a labor camp, followed by internal exile. / Unknown Author

Alexander Solzhenitsyn in a quilted camp jacket just after being discharged. Kok-Terek, Kazakhstan, March 1953. In 1945 Solzhenitsyn was sentenced to 8 years in a labor camp, followed by internal exile. / Unknown Author

In 1991, the biggest Soviet newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda published Solzhenitsyn’s interview with Spanish TV where he added 44 million victims to this figure; these were Soviet citizens who perished during World War II. This brought the overall number of Stalin’s victims to around 110 million. But the total population of the Soviet Union before the War was 170 million, as the 1939 census showed. Needless to say, these numbers openly contradict each other.

Such exaggerated figures were fed to the Soviet public not only by dissidents but also by the members of the Communist Party. Historian Roy Medvedev in 1990 got a spot in the Central Committee of the CPSU, and he claimed that the number of victims of political repression in the USSR from 1927 to 1953 was 40 million.

Victims of Stalinist repression have been counted not only by dissidents and CPSU officials but also by professional historians in the West. Robert Conquest was the scholar who coined the term “Great Terror,” and he claims that about 9 million people were imprisoned in the USSR by the end of 1939.

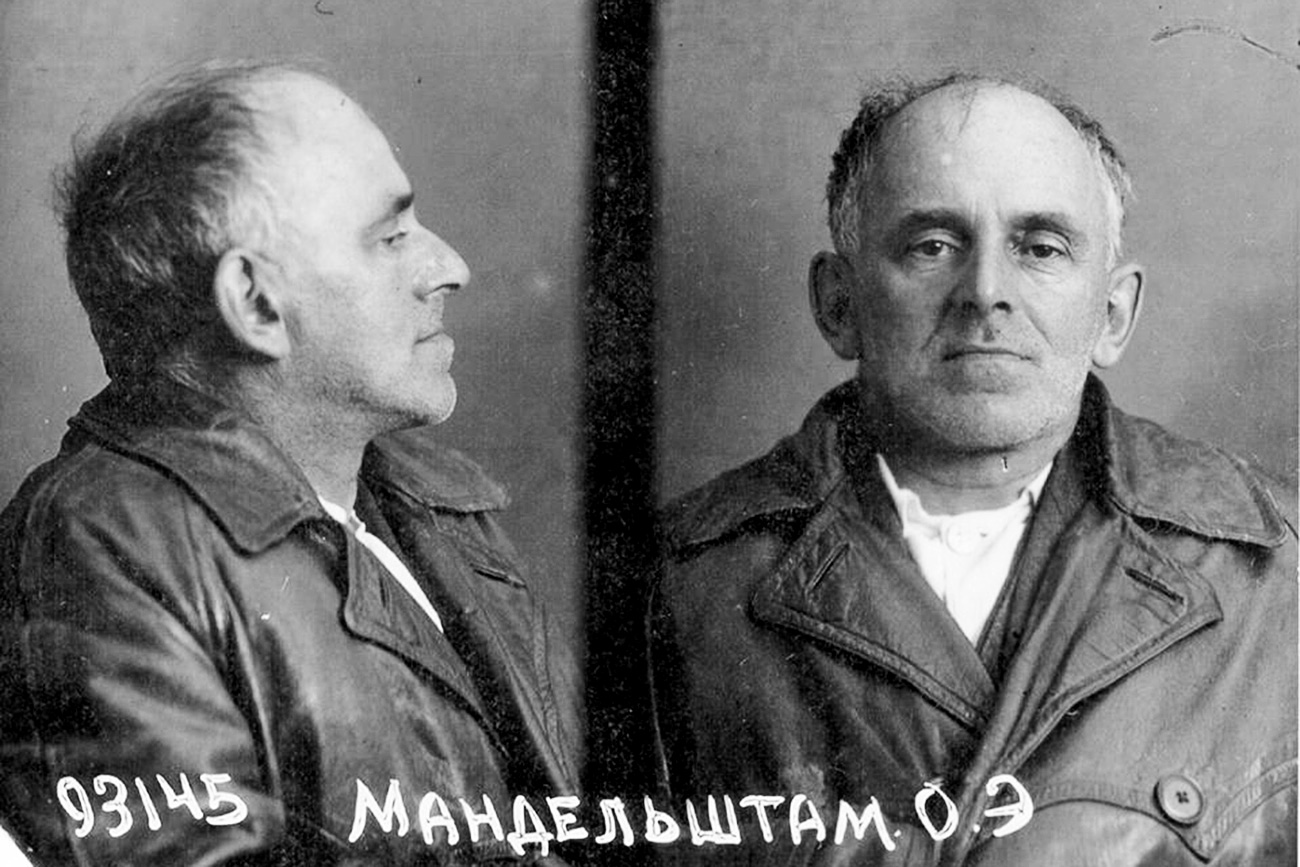

The last photo of the poet Osip Mandelstam, 1938. / Archive image

The last photo of the poet Osip Mandelstam, 1938. / Archive image

Though smaller than previous estimates, this figure still is five times greater than reality. Historian Viktor Zemskov, considered to be one of the leading specialists on this topic, studied the statistical data of the Soviet penal system, (Roginsky says that the Soviet authorities carefully documented the cases of those arrested), and he calculated that in 1940 there were around 1.9 million people in Soviet jails and prison camps.

In 1990, KGB chief Vladimir Kryuchkov said that from 1930 to 1953 nearly 3.8 million people were jailed, and 786,000 were sentenced to death. The accuracy of these numbers is not challenged by professional historians.

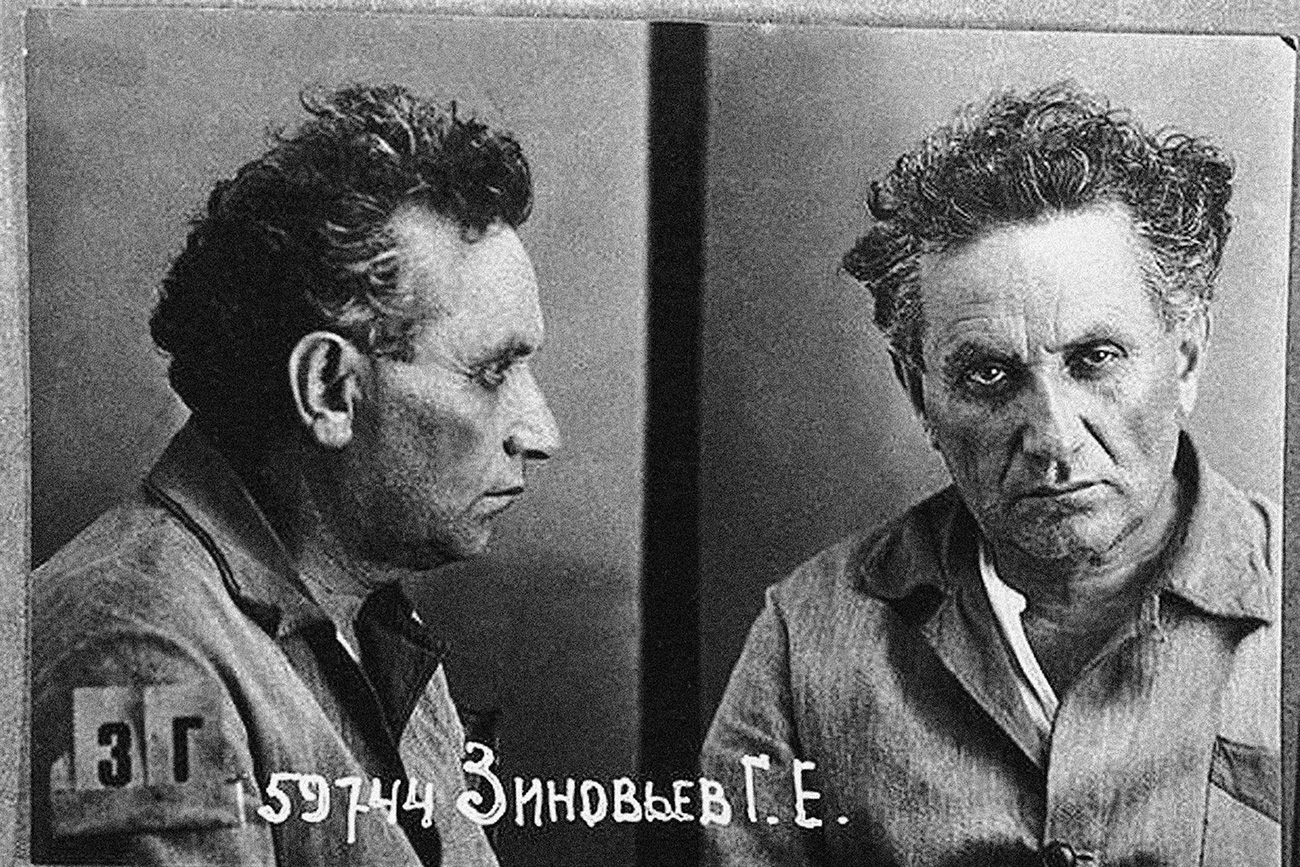

A mug shot of Grigory Zinoviev. / Getty Images

A mug shot of Grigory Zinoviev. / Getty Images

As Zemskov recalled, the public simply did not want to believe Kryuchkov, thinking the numbers were falsified, and referred instead to The Gulag Archipelago with its fantastic tens of millions of victims.

Given the fact that Soviet authorities passed more than 600,000 death sentences in just two years (1937-1939), the numbers presented by the KGB chief looked plausible. However, it was not enough for the public, and so one cannot escape the question why it was like this? Why did people tend to believe exaggerated estimates and reject the facts?

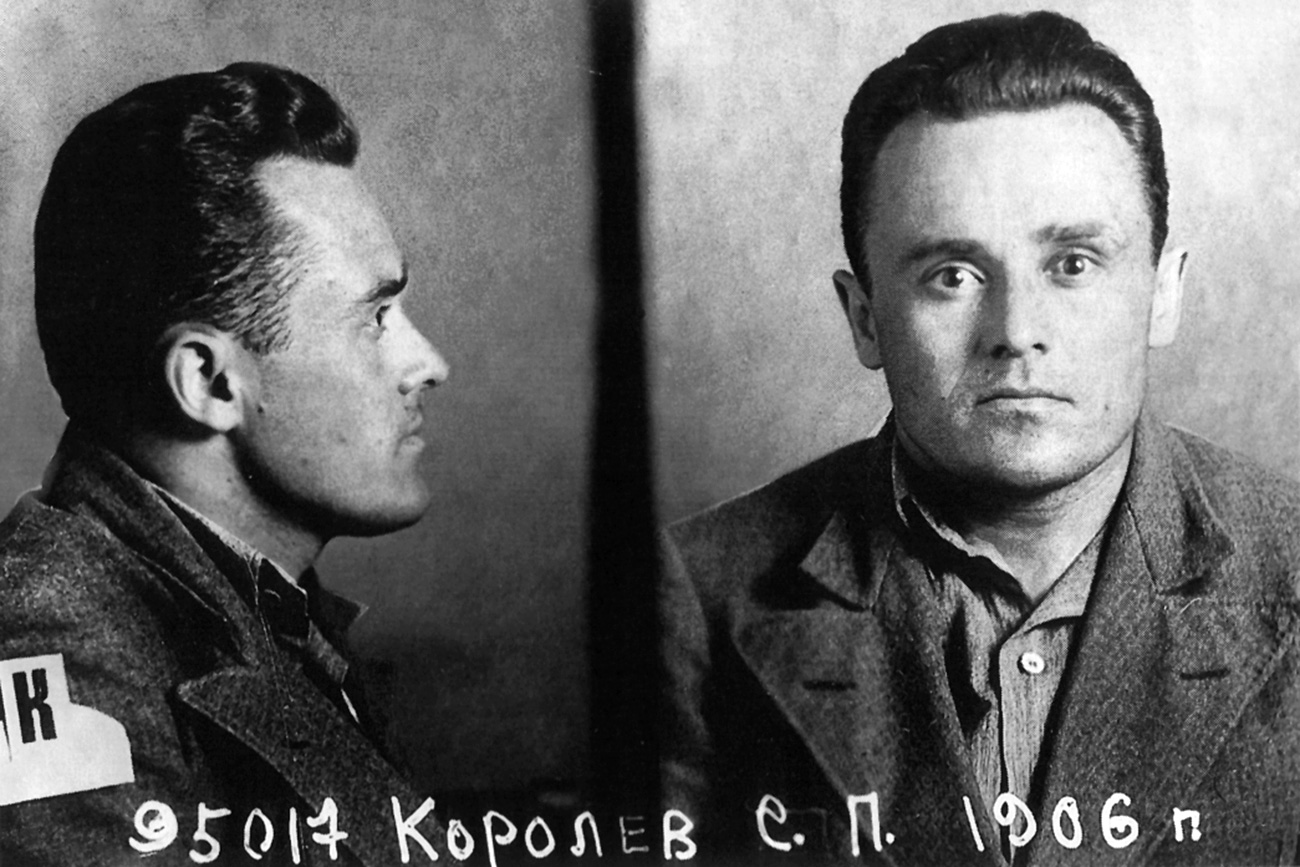

Sergei Korolev in prison, 1938. / Archive image

Sergei Korolev in prison, 1938. / Archive image

Sergey Kara-Murza, a social scientist specializing in Soviet history, thinks he has the answer. He argues that although the purges of 1930s were a wrenching phenomenon in Russian history, “there cannot be an objective analysis.”

“The pain caused by the lives loss is still too great, and any attempt to make an unbiased analysis looks amoral. Relatives and even sons of politicians murdered in the 1930s went on to play a prominent role in the political arena during perestroika,” Kara-Murza wrote. “The very image of repressions is such a powerful political tool that the means for its creation and use are guarded with strict but not always obvious censorship.”

Kara-Murza’s thought about using the repressions as a political tool today is quite in line with what political scientist Maria Lipman wrote in Foreign Affairs about the impact of the de-Stalinization campaign during Perestroika, at the core of which was the issue of Stalin’s terror.

Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn's widow Natalya reacts at the opening of the Gulag history museum in Moscow, Oct. 30, 2015. / AP

Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn's widow Natalya reacts at the opening of the Gulag history museum in Moscow, Oct. 30, 2015. / AP

De-Stalinization “radically delegitimized the Communist regime. By the end of 1991 the meltdown of Soviet Communism was followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union.”

Paradoxically enough, the de-Stalinization process that buried the USSR was not always founded on truth and reality.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox