Nicholas II with family.

Archive PhotoSome people will do anything to get recognized, but this lot really took the biscuit. They claimed to be survivors of the infamous execution of the Romanov family in 1918 – and despite some people falling for their untruths – they were ultimately cast aside as either mad or desperate. The Russian crown remained out of reach to this untrustworthy lot. The real Anastasia was killed with her parents and siblings on July 17, 1918 – but this was not confirmed for absolute certainty until the missing remains of the Romanov sister was unearthed and identified in 2008.

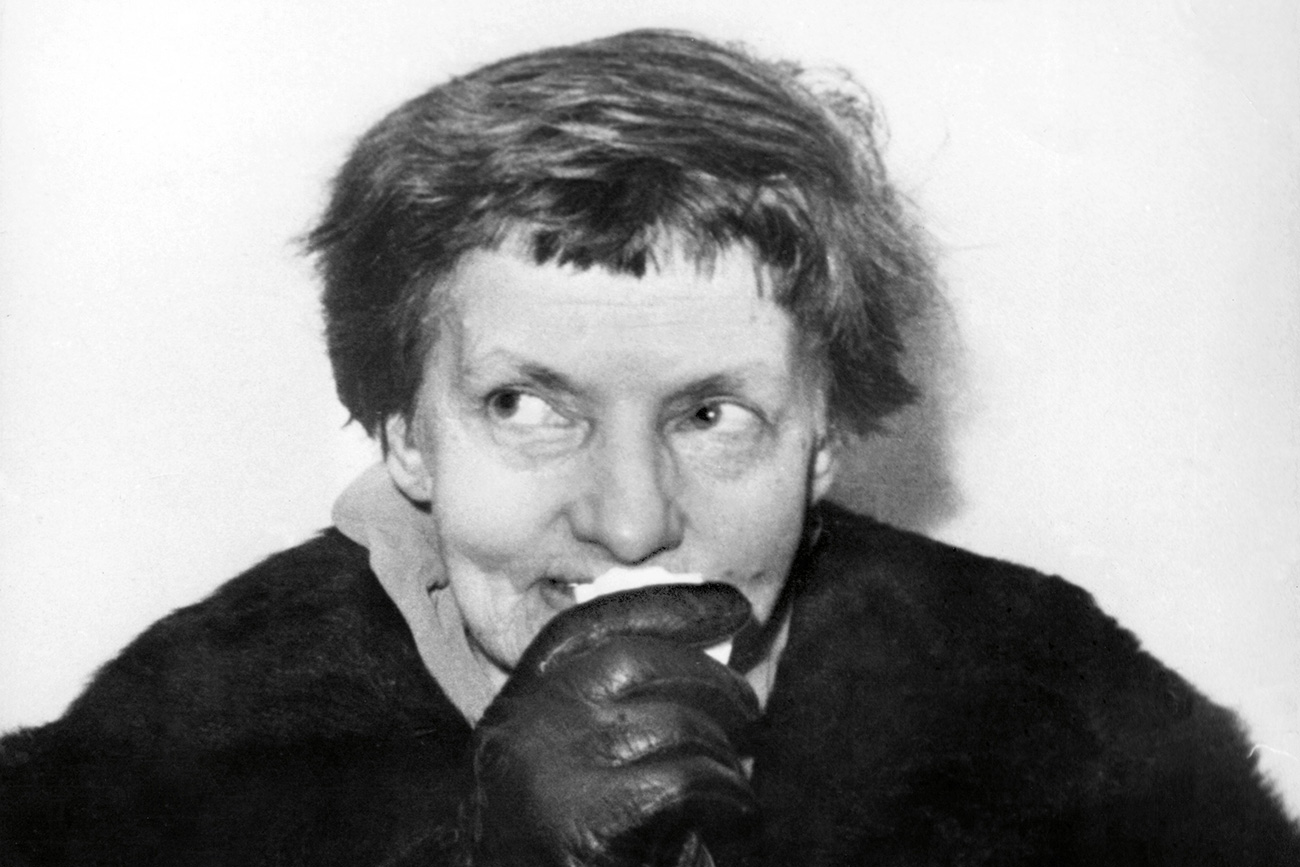

Anastasia Manahan, also known as Anna Anderson, 1955, Germany / AFP

Anastasia Manahan, also known as Anna Anderson, 1955, Germany / AFP

This impostor – known as Anna Anderson – claimed to be the fourth and youngest daughter of the Romanov family. However, despite fooling many of the Imperial elite, she was found out to be Polish factory worker Franziska Schanzkowska (with a history of mental illness) after an investigation funded by the Tsarina of Russia’s brother.

“Anna’s” story began in 1920 when she tried to commit suicide and was sent to a mental health center in Berlin. She refused to tell her name to anyone. One of the patients took her for the Grand Duchess and later this legend was supported by Russian immigrants.

Two years later Anna started telling people herself that she was in fact the Grand Duchess Anastasia.

In 1928 she moved to the U.S. and started sponging off Russian princess Xenia Georgievna, who was distantly related to the Romanov family. However, after a failed attempt to prove her blue blood, Anna moved back to Germany.

For more than 20 years she struggled to get her name recognized by the European courts, but to no avail. In 1968 she moved back to the U.S. where she married a wealthy man and got American citizenship.

Anderson died in 1984 in Virginia. DNA tests taken since her death do not back up her claim of being a Romanov.

Eugenia Smith / Archive Photo

Eugenia Smith / Archive Photo

Another infamous pretender to Anastasia’s title was Eugenia Smith, real name Eugenia Drabek Smetisko. She was an artist and writer of Ukrainian descent, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1929 from Bukovina.

Smith rocked up in Chicago in 1963. She presented a book to a publisher in the Windy City, which she said was a manuscript given to her by the Grand Duchess herself. Doubting her tale, the publisher asked her to take a lie detector test, which Smith failed. Bizarrely, she then changed her statement, instead claiming to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia and amazingly passed the test.

Her “Autobiography of HIH Anastasia Nicholaevna of Russia” recounts “her” life in the Imperial family and how she escaped the execution by the Bolsheviks (a great work of fiction).

Eugenia died in 1997 in Rhode Island and was buried in the Orthodox monastery.

Marga Boodts / Legion Media

Marga Boodts / Legion Media

Marga Boodts is considered to be one of, if not the most, successful aspirants to the Romanov family. She claimed to be Olga, the first daughter of Tsar Nicholas II.

Marga first appeared in France in the wake of WWII. She collected money from the public for the Grand Duchess, who she claimed miraculously escaped the execution of the Romanov family. Later Boodts was arrested for fraud. In court she argued she was a Polish szlachta (a legally privileged noble class).

Some years later in 1950, Marga appeared again, but denied any knowledge of her previous fraudulent activities. Boodts somehow managed to convince Nikolaus, the Hereditary Grand Duke of Oldenburg and Wilhelm (the German Crown Prince) who supported her financially until their death, in her veracity.

For a long time Marga kept her silence, yet when Anna Anderson (look back at number 1) became famous, she also made her claim public. Boodts did everything in her power to destroy Anderson’s credibility. She wrote a book to tell the story of her “family,” yet it was never published.

Boodts died in 1976 in Sala Comacina, Italy where she lived the rest of her days in solitude, refusing to meet any journalists.

Polish spy Colonel Michael Goleniewsky / Getty Images

Polish spy Colonel Michael Goleniewsky / Getty Images

Michael Goleniewski was a Polish officer and counterintelligence agent, who cooperated with the Soviet KGB during the late fifties while employed by his country’s secret service.

Goleniewski became a triple agent by providing the CIA with Polish and Soviet secrets. In January 1961, he defected to the U.S. and officially started working for the CIA. The same year a Polish court declared him dead in absentia.

Some time later, while working in the U.S. he claimed to be Tsarevich Alexei, the youngest child and the only son of Tsar Nicholas II. According to Goleniewski, the whole family was still alive. Very few people believed him though.

In order to prove his blue blood, Goleniewski tried to find his sisters. He had a “reunion” with the aforementioned impostor Eugenia Smith, claiming she was his sister. Smith returned the favor, recognizing Goleniewski as her brother.

However, Goleniewski’s documents showed that he was born in Poland, 18 years after Tsarevich Alexei was born. In response, the pretender claimed that he was a hemophiliac (Tsarevich Alexei was born with this genetic disorder) which made him look younger than he really was. Few believed him and he was fired by the CIA because of his lies.

Goleniewski fought to regain his “rightful” name until his death in 1993 – but had no luck.

Ceclava Czapska and Nicolas Dolgoruky in 1919 / Legion Media

Ceclava Czapska and Nicolas Dolgoruky in 1919 / Legion Media

Ceclava Czapska was first noticed in 1919 in Romania where she was taken under the protection of Queen Marie of Romania. She and Russian Prince Nicolas Dolgoruky – the son of General Alexander Dolgoruky – married there. This is when she started claiming to be Grand Duchess Maria.

According to her, all members of the royal family, except her “dad” Nicholas II and the servants, escaped from being executed. Ceclava officially recognized the authenticity of the aforementioned Anna Anderson and Marga Boodts (she knew the latter in person).

She died in 1970 in Rome – a DNA test after her passing denied any links to the royal family.

Some time after a man called Alexis Brimeyer claimed connection to the Romanovs and other European thrones. The son of a Luxembourgish engineer, Brimeyer was a native of the Belgian Congo. He said that all members of the Romanov family were executed except for his “grandmother” Maria (Ceclava Czapska), who “left” him the Russian throne.

Brimeyer claimed Russian Prince Dolgoruky was his grandfather and used fraudulent combined titles like Prince d’Anjou Durazzo Durassow Romanov Dolgorouki de Bourbon-Conde, which he was later sued for by the real Dolgoruky family. After failing to impress with his fake names, he coined himself His Serene Highness Prince Khevenhüller-Abensberg - only to be sued for the second time by Princess Khevenhüller.

Bizarrely, a few years later he received a passport from the Principality of Sealand (a micronation that claims a platform in the North Sea, 12 kilometers off the coast of Suffolk, England) with the name His Highness Prince Alexis Romanov Dolgoruky.

Alexis tried many other ways to ennoble himself and even asked a number of aristocrats to adopt him. The “unfortunate prince” frantically tried to carve out royal ties until his death in 1995 in Madrid.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox