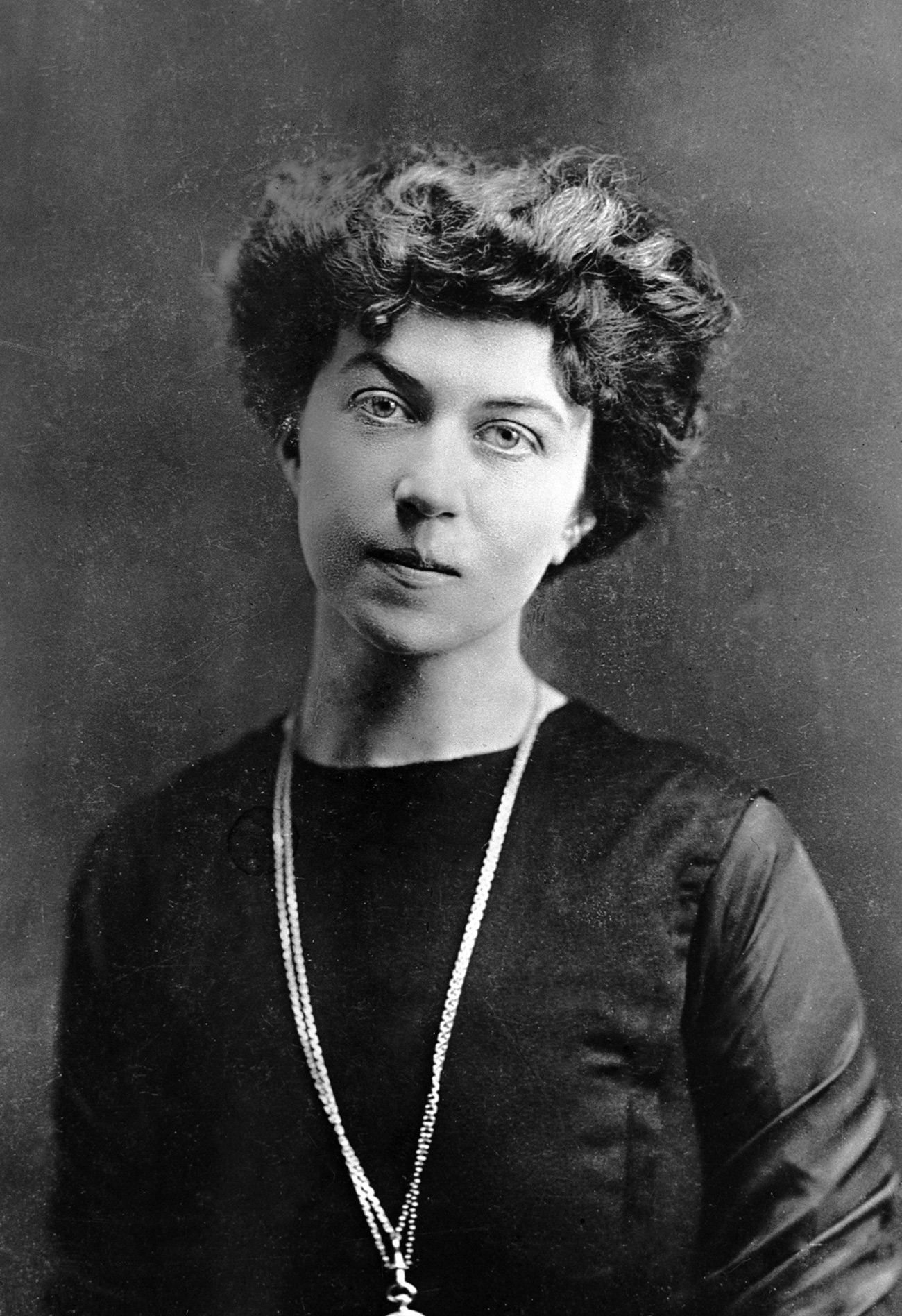

The diplomat Alexandra Kollontai. A photograph from the family archive, 1908. Reproduction.

R. Popovkin/RIA Novosti

Russian revolutionary Catherine Breshkovsky. / Published by Little, Brown and Co, Boston, 1918; photographer unknown

Russian revolutionary Catherine Breshkovsky. / Published by Little, Brown and Co, Boston, 1918; photographer unknown

When the February Revolution raged in Russia in 1917 she was already 73-years-old. Even at this venerable age Catherine Breshkovsky was still exiled in Siberia for her role in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

Her age was no barrier though, and she managed to play an influential hand in the events leading up to the 1917 uprising. She was known as the “Grandmother (Babushka) of the Russian Revolution” and gained a loyal following thanks to her decades of struggle against the Tsarist regime.

Breshkovsky’s political activism kicked off in the 1870s when, together with other young radicals, she tried to attract public support for the revolutionary cause. Not long after she was arrested and sentenced to katorga labor, a hard form of penal labor.

After spending several backbreaking years in a prison she left Russia (Switzerland and America) before returning during the 1905 Revolution. Around this time she participated in the creation of the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (SR). Despite her pious views, Breshkovsky encouraged the party’s fighting body to use terrorist methods.

She was arrested again and sent to Siberia where she was forced to wait until the events of 1917 when political prisoners were released. On her return to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) she was allocated a special railway carriage and at every stop she was welcomed by orchestras and saluting military regiments.

“Liberated Russia awaits Babushka in order to pay her respect and share with her the great happiness of long-awaited freedom,” the liberal paper Rech (Speech) wrote.

When she finally reached the capital, the reception waiting for Breshkovsky was beyond anything she could have imagined. Ministers came to the railway station to meet her and she was taken to the Winter Palace where she was given accommodation

She supported the provisional government and hated the Bolsheviks. She urged people to slaughter them like “wild dogs.” However, Breshkovsky was so upset about the October Revolution that she emigrated from the country. In the U.S. she attempted in vain to raise funds for the fight against the Bolsheviks. Later on, in the twenties, she called time on her political activity and she died in Czechoslovakia in 1934 aged 90.

Maria Spiridonova (center, in glasses), 1905. / Getty Images

Maria Spiridonova (center, in glasses), 1905. / Getty Images

Maria Spiridonova is remembered as one of the Russian Revolution’s most prominent figures. She belonged to the SR Party and spent most of her life in exile and prison - under both the Tsarist and Soviet regimes. Due to her unyielding willpower she was known as the “Blessed Virgin of SR.”

Ten years before 1917 she was already well-established as a revolutionary activist and in 1906 she even killed a provincial official for his role in suppressing a peasant unrest. Despite being a terrorist, many Russians sympathized with her and after she was arrested, beaten, and possibly raped the public vented its anger. At first she was sentenced to death but the court softened its stance and instead sent Spiridonova to the prison in Siberia for ten years. The Cossack officer who interrogated her was later killed by revolutionaries.

She was only freed after the February Revolution and upon returning to Petrograd became an active politician. Spiridonova was appointed one the leaders of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Left SR) after the SR split.

She did not approve of the Bolshevik methods but understood people followed them. Hence she supported the alliance between two the parties after the October events when the Bolsheviks rose to power.

However, this alliance was short-lived. The Left SR did not accept the conditions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany negotiated by the Bolsheviks. As a result, the party tried to stage a coup in July 1918 and Spiridonova was heavily involved - but when it failed she was again arrested.

The strong-willed woman continued to be persecuted by the Soviet regime and was arrested and exiled several times. In 1937 she was locked up for the last time and eventually executed by firing squad in September, 1941.

Alexandra Kollontai, activist of the international women's movement. / RIA Novosti

Alexandra Kollontai, activist of the international women's movement. / RIA Novosti

Alexandra Kollontai was also of noble descent but unlike Breshkovsky and Spiridonova she did not belong to the SR - instead she was a member of the Bolsheviks. She is most famous for her feminist views and as a proponent of free love.

She became the first female minister in history. In the cabinet formed by the Bolsheviks following the overthrow of the provisional government in October 1917 she was given the post of welfare minister. Although not holding the position for that long, she still managed to improve women’s rights in Russia. For her endless energy and passion she was dubbed the “Valkyrie of the Revolution.”

During the civil war she was in charge of political and propaganda work within the Red Army regiments fighting the Whites in Ukraine. She was there with her husband Pavel Dybenko, a Soviet military leader. It’s believed her marriage to Dybenko was the first not to be blessed by the church but registered with the civil authorities in Russia.

After being sidelined in the party leadership in the early twenties, she pursued a diplomatic career as an ambassador in Mexico and Scandinavia. She was only the second female ambassador in the USSR.

She vehemently believed women should have equal rights to men and wanted to see traditional family values thrown out, with more emphasis put on society. Her concepts were too radical for the times though, despite the twenties witnessing huge social experiments in Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox