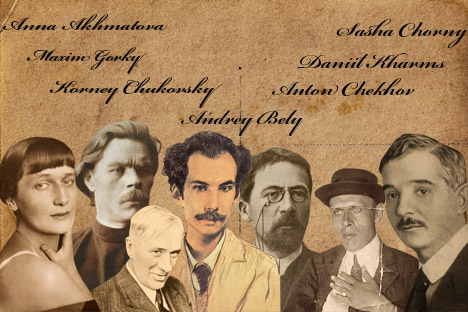

Pictured L-R: Anna Akhmatova, Maxim Gorky, Korney Chukovsky, Andrey Bely, Anton Chekhov, Daniil Kharms, Sasha Chorny.

Slava Petrakina / RBTHWhen the 19-year-old Boris Bugayev decided to dedicate himself fully to literature, he examined his cumbersome birth name, which is derived from the Russian for “meathead”, and decided that it didn’t fit with his symbolist poetry and personal romantic image. He turned to his friend Mikhail Solovyev, the younger brother of the philosopher Vladimir Solovyev, for inspiration. Solovyev gave him the first name Andrey, who, according to legend, was the first of the 12 apostles to visit Russia, and the surname Bely, which means “white” – a color symbolizing purity and wisdom. And so the great writer we know as Andrey Bely (1880 – 1934) was born, adopting a new name in a deliberate parallel with his entry into a new artistic and personal era.

As it happens, there was a Russian writer with the opposite pen name to Bely. You might be forgiven for assuming that Alexander Glickberg (1880 – 1932) chose his name of Sasha Chorny (“black”) as an ironic nod to his satirical style, but it actually dates from his childhood. He had a brother also called Alexander – which is commonly shortened to Sasha in Russian – who was blond. Sasha Chorny’s own dark hair was a neat way of differentiating the two, and the nickname stuck.

Pseudonyms based on an abstract or moral quality a person possesses are called phrenonyms. The young writer Alexey Peshkov (1868 – 1936) didn’t want to use his real name, which comes from the Russian word for “pawn”, so he chose Maxim Gorky (“bitter”) instead. This name was a fitting description of Gorky himself and the subjects he wrote about. Orphaned at a young age, he spent years in poverty, living as a tramp and working menial jobs, and his novels were often devoted to the hardships faced by the poor. As an interesting aside, Gorky’s father, Maxim Sr., was also known by the nickname “bitter”, thanks to his acerbic attitude.

Daniil Yuvachev (1905 – 1942) eventually settled on the pen name Daniil Kharms after testing out dozens of others. Derived from the English word “charm”, it was both catchy to a Russian ear and meaningful to Kharms, who believed that poems can be seen as magic spells – words in a particular order that evoke certain feelings in people. The image of a wizard is a recurring theme in his short stories, and he wrote that his use of a “magical” pseudonym was intentional.

One reason why Kharms decided to use a pseudonym was because his father, Ivan Yuvachev, was a respected old revolutionary turned theologian, and Kharms wanted to retain a measure of anonymity. Anna Akhmatova (1889 – 1966) also gave up her birth name of Anna Gorenko because of her father, who apparently told her not to disgrace his name when he discovered her poetry. “I don’t want your name either,” she replied.

In a neat twist, Lidiya Chukovskaya, a writer and Akhmatova’s friend, who wrote about this exchange in her memoirs, had her father’s pen name as her actual surname. The illegitimate Nikolay Korneychukov (1882 – 1969) was originally given his mother’s last name, but he modified it to Korney Chukovsky, before going on to become on the most famous Russian children’s author. He acquired a passport in this name after the 1917 October Revolution and passed the surname Chukovsky on to his children.

Anton Chekhov (1860 – 1904) is remembered under his real name, although he used numerous alternatives during his life. Around 40 of Chekhov’s pen names have been discovered, but it is possible that more stories under obscure names may still turn up. Chekhov chose witty and bizarre pseudonyms, such as My Brother’s Brother, Doctor Without Patients, Nut #6, The Prosaic Poet, and Don Antonio Chekhonte.

Chekhov’s most common pen name was Man Without a Spleen – a nod to his medical training that he used for 119 short stories and five articles. Perhaps the reason that none of these fantastical pseudonyms stuck, however, was the fact that Alexey Suvorin, Chekhov’s publisher, insisted that he only used them for satirical articles, publishing any serious work under his real name.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox