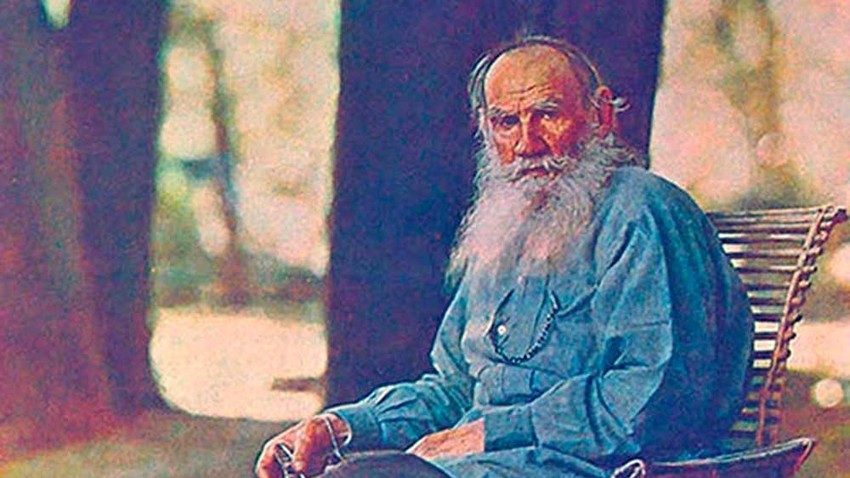

Leo Tolstoy in front of his country house in Yasnaya Polyana

Sergei Prokudin-GorskyIn chilly late October 1910, the 82-year-old Leo Tolstoy unexpectedly left his beautiful country home in Yasnaya Polyana and set off into the night. Three weeks later he died of pneumonia at a little rural railway station Astapovo. What made the author run

These are the mysteries that Pavel Basinsky’s book Leo Tolstoy: Flight from Paradise spends 500 pages

|

| Pavel Basinsky. Leo Tolstoy: Flight from Paradise by Glagoslav Publications, 2015 |

The inaccurate image of Tolstoy leaving home on foot, with cane and knapsack, is surprisingly persistent. With his peasant smock and flowing grey beard, looking “like a character from a fairy tale,” the elderly writer walked out of his family home straight into the realm of myth. A legend in his own lifetime, Tolstoy’s story comes to us through a polyphonic chorus of friends, relatives, secretaries,

The portentous seriousness of Tolstoy’s manner in his final years is amplified by the gathering “Tolstoyans”, ready to make this man a myth. “Life isn’t a joke,” he wrote, in his last letter to Sofia. Ultimately, some facts surrounding Tolstoy’s death remain obscure, despite Basinsky’s years in the archives. Sofia later wrote in her diary: “What happened is incomprehensible, and will forever be beyond our understanding.”

It sometimes feels almost as much of a mystery, to a non-Russian reader, how this drily enthusiastic tome of research should have been so successful, winning Russia’s prestigious Big Book Prize in 2010. The answer lies in its mythopoeic qualities, some of which are lost in translation; Basinsky writes of elements in Tolstoy’s myth being “deep-seated in the Russian consciousness.”

The English edition has a telling recommendation on the blurb: “Flight from Paradise will be of particular interest to international researchers studying Leo Tolstoy’s life and works,” with a vague hope that it will reach a “broader audience.” Huw Davies and Scott Moss have produced an English text full of interesting details, but a pacier translation (like Catherine Porter’s version in Rossica magazine) might have had more chance with a general readership.

The 2009 film The Last Station starring Christopher Plummer and Helen Mirren, transmitted one version of the Tolstoy-death story to Anglophone filmgoers, with a focus on the pressures of fame and success. Elif Batuman’s chapter on “Who

Basinsky shows how the idea of departure had haunted his life and work for many decades before his death. Tolstoy abandoned his university degree in 1847 and fled to Yasnaya Polyana; sixty years later, this house that once represented all of Russia to him, had become a nightmare where “I am being boiled like in hell.”

Flight from Paradise catalogues both the author’s own “dress rehearsals” for his final departure and the same tendency among many of his characters “forever leaving and running off somewhere”: Bolkonsky flees the army, Natasha Rostova runs off with Kuragin, Pierre roams

Extracts from Sofia’s notebooks show how differently the married couple saw the world. Basinsky juxtaposes their diaries. She writes: “I am gratification, I am a nanny, I am a familiar item of furniture, I am a woman” while her husband complains she is spoiled and angry and that: “I cannot work … I cannot sleep.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox