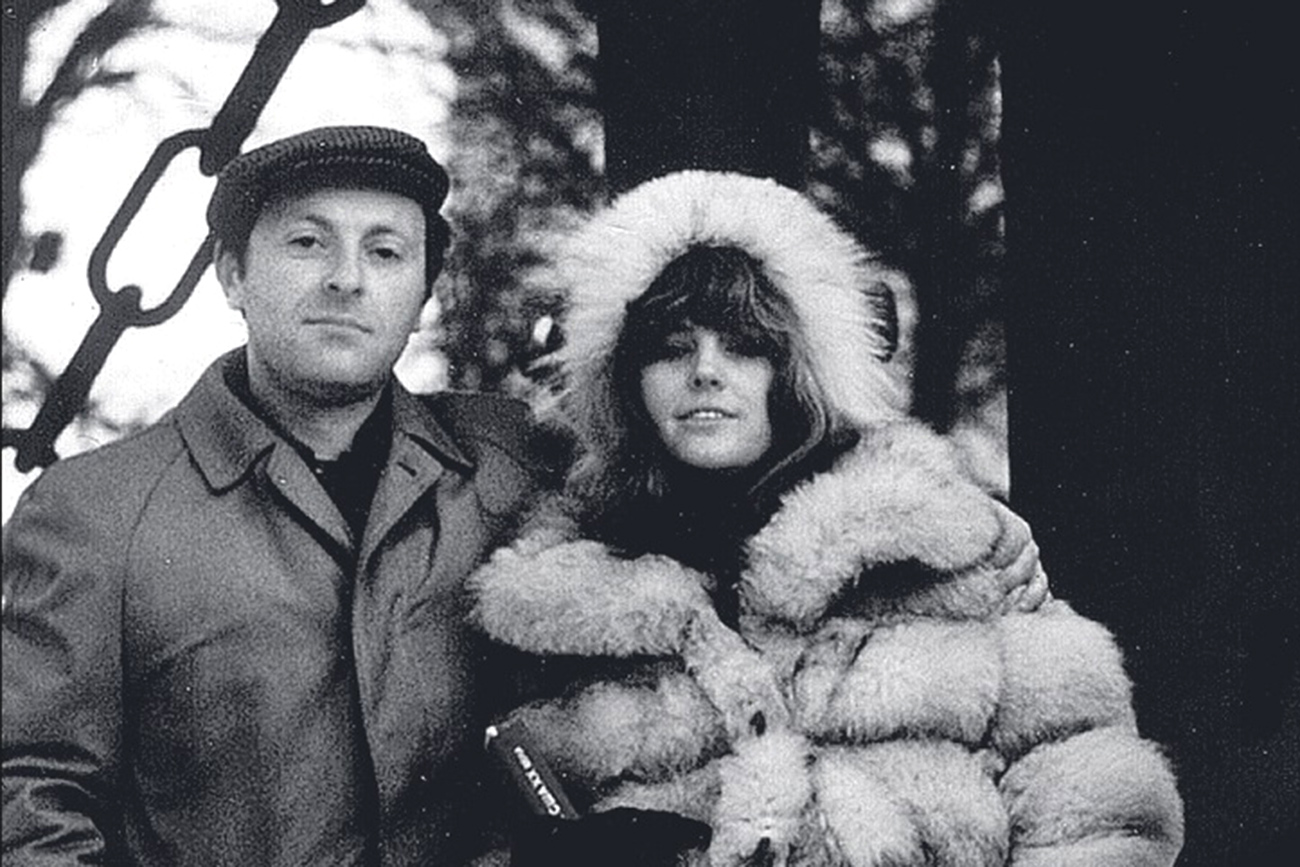

Joseph Brodsky and Ellendea Proffer in St. Petersburg, 1970. Picture taken by Carl Proffer.

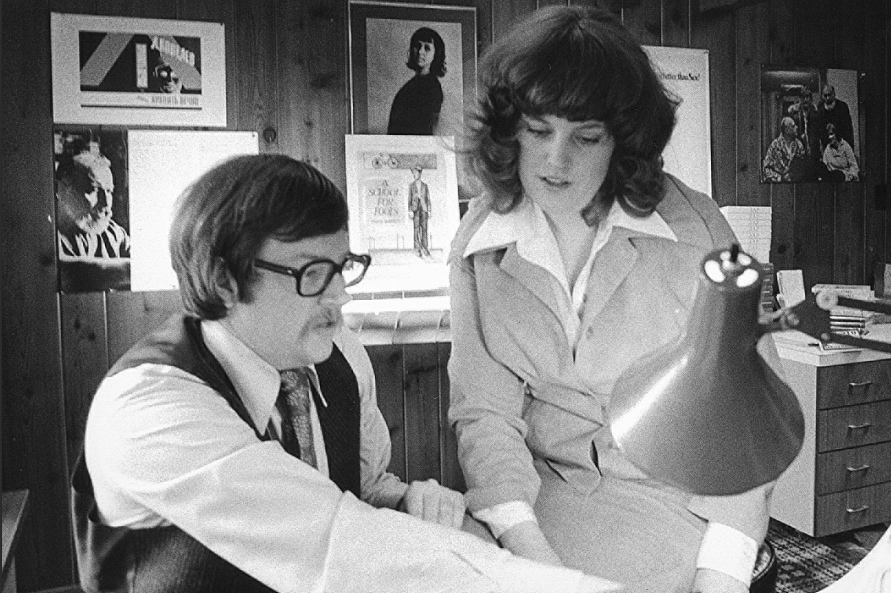

CorpusTogether with Ardis, the Michigan-based publishing house they established solely for Russian literature, the young American professor Carl Proffer and his wife Ellendea published literary works in both English and Russian that were banned by Soviet authorities. These included works by Nabokov, Brodsky, Zamyatin and other authors.

Starting in 1969, the Proffers, who specialized in Russian literature and had perfect command of the Russian language, traveled to the USSR many times, met legendary people of letters, received "dangerous" manuscripts and sent them to the West.

Shortly before his death in 1984, Carl Proffer decided to write down his recollections, and his wife later published his book, The Widows of Russia. However, certain parts of the book, especially memories of Brodsky, were not published at that time. The capricious Russian poet did not want published what Carl had to say, and he even threatened a lawsuit, despite his long friendship with the Proffers.

Brodsky's first days in the U.S. (Ann Arbor, Michigan), 1972. Source: Corpus publishing house

Brodsky's first days in the U.S. (Ann Arbor, Michigan), 1972. Source: Corpus publishing house

"I think he felt betrayed that his friend Carl looked at him objectively and that he permitted himself to speak sharply about certain moments," said Ellendea.

Proffer and Brodsky's first encounter was in Leningrad during one of the Proffers' first visits to the USSR. Osip Mandelshtam's widow, Nadezhda, insisted they meet this interesting poet. "It's not clear how she understood that we would play a decisive role in his fate," said Ellendea.

The Proffers met Brodsky and his friends many times. They held his poetry in high esteem, frequently published his poems in the U.S. and helped him after he came to America. Carl eventually found Brodsky a teaching job at Michigan University, where he himself worked.

Carl and Ellendea in the Ardis publishing house. Source: Corpus publishing house

Carl and Ellendea in the Ardis publishing house. Source: Corpus publishing house

In 2015, Ellendea presented her recollections about Brodsky to the Russian audience with her book, Brodsky Among Us (Corpus publishing house). "I was surprised that Joseph was considered practically a state poet, a martyr, since he was not one at all." She wanted to tell people what he was like in reality: he himself wanted to leave the Soviet Union, that no one kicked him out and he did not want to return there after Perestroika.

Also, as his friend, Ellendea found it strange to see monuments and museums dedicated to a person who is more alive than anyone. In her memoirs, Brodsky is very lively, sometimes nervous, sometimes arrogant, but definitely a person with incredible talent and charisma. She was impressed by his attitude towards his vocation. He truly thought that a poet has an important mission.

She spoke about the first years of his teaching American students. At first he was a horrible professor, with bad English. "In America, the first four years of university students do not have a specialization. Among his students were mathematicians, biologists, but he thought they had to know everything! If they didn't know everything that he knew, which was an enormous range of literature or Greek mythology, he thought they were ignorant." Later, however, he softened his attitude and adapted to the American system.

Ellendea's memoirs contain excerpts from her husband’s diary. "I was often asked what these excerpts are, since they were never published. And in the end, I decide to reveal them."

This year, Carl Proffer's book, The Widows of Russia, was published in Russian under the title Bez Kupyur, which means 'unexpurgated.' It consists of two parts: Carl's recollections of Brodsky, and parts of the original edition of The Widows of Russia with Ellendea's notes, which she thought would be important to include after more than 20 years since the first edition.

Carl wrote about his friendly meetings with Brodsky in his Leningrad apartment. Once, having nothing to do, one of the poet's friends began opening and closing Brodsky's drawers and noticed a manuscript. It turned out to be a letter that Brodsky had intended to send to Brezhnev, asking him to pardon and annul the death penalty for two culprits in the "hijacking affair," Eduard Kuznetsov and his accomplice Dymshits.

"He compared the current Soviet regime with other regimes, including Nazi and czarist (…) He wrote that the people had suffered enough and that there was no point in adding the death penalty. It was clear that if Joseph had sent the letter, he would be seriously risking his freedom," wrote Carl.

Brodky in Ann Arbor, 1970. Source: Corpus publishing house

Brodky in Ann Arbor, 1970. Source: Corpus publishing house

Proffer also remembers the important role that his first and greatest love, Marina Basmanova, played in Brodsky's life and art. He dedicated many poems to her, seeking her image in many other women.

"Our thoughts were occupied with Russia and our work for Russia," Ellendea's quote graces the Russian book's cover. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine who else has done so much for Russian literature by preserving so many manuscripts that could have been destroyed or hidden in the KGB archives forever.

"After the publication of Carl's book I was told that I myself am now a literary widow," Ellendea laughed. During their many travels to the Soviet Union, the Proffers often visited Nadezhda Mandelshtam.

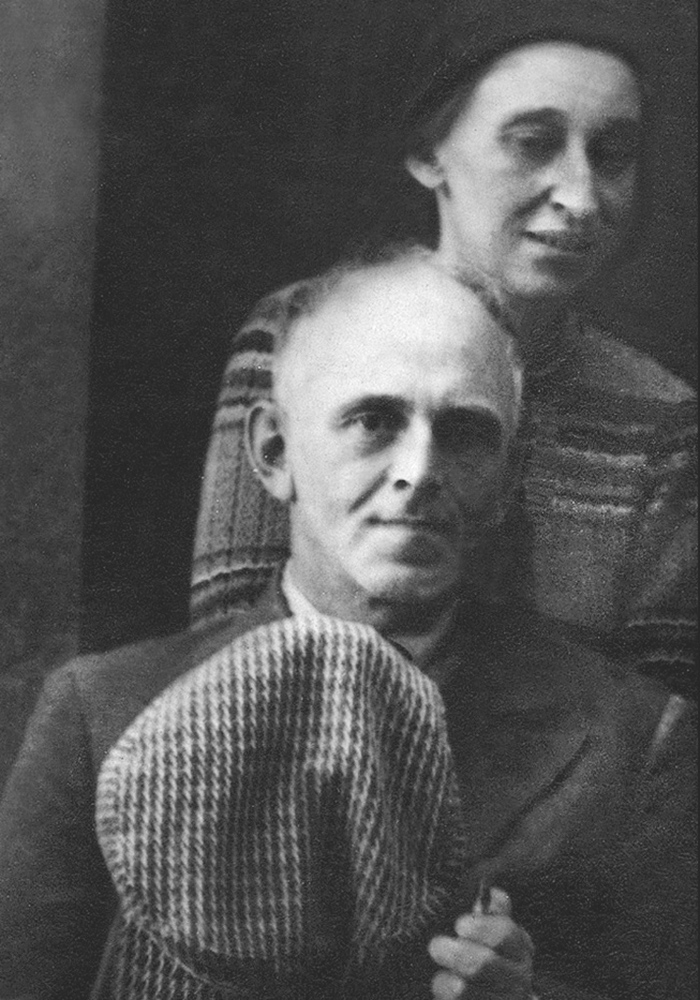

Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam, 1937. Source: Corpus publishing house

Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam, 1937. Source: Corpus publishing house

Until her death Nadezhda's main goal was to preserve and publish the poems of her husband, poet Osip Mandelstam, who had been deported to a gulag camp and died there in 1937 under unknown conditions. It’s not even known where he is buried. Ellendea felt that Nadezhda suffered without him until her very death. "When we first gave her Osip's Voronezh Notebooks, which we had published, she was incredibly grateful," remembered Ellendea.

All widows took great risks by communicating with foreigners. Since Stalin's time they remained extremely frightened, which is why Nadezhda asked the Proffers not to stop the taxi in front of her house when they came over, and she looked out the window to see if they had been followed.

The most important thing for the widows was to pass on the poetry and their recollections. Carl was amazed by the tightknit network of writer widows, which was a very influential group. Nadezhda Mandelshtam could easily call Bulgakov's widow and ask her to receive the young Americans.

Elena and Mikhail Bulgakov, 1930s, photo be B. Shaposhnikov. Source: Corpus publishing house

Elena and Mikhail Bulgakov, 1930s, photo be B. Shaposhnikov. Source: Corpus publishing house

Thanks to one of these simple phone calls the Proffers were introduced to Lilya Brik.

Brik, who was Mayakovsky's muse, can also be found in Carl's book. While Nadezhda Mandelshtam was poor and Elena Bulgakova was a socialite with a modest lifestyle, Lilya Brik led a sumptuous existence by Soviet standards. She had an enormous apartment with rugs and paintings (most of which depicted her).

Lilya Brik and her husband Vasily Katanyan, Moscow, circa 1975. Source: Corpus publishing house

Lilya Brik and her husband Vasily Katanyan, Moscow, circa 1975. Source: Corpus publishing house

The Proffers saw something diabolic in this woman, who had conquered many hearts. She was almost 90 years old but was still lucid and witty, and she loved speaking about that era and obviously about Mayakovsky.

"He loved me so much," Carl quoted her in his book. "At her age she was even able to flirt with Carl," said Ellendea. It was Brik, in Carl's opinion, who made a state poet out of Mayakovsky by writing Stalin a letter after the poet's death, saying that his poems must not be forgotten.

Encounters with Ellendea will be held in Moscow on April 14, 18 and 20, and in St. Petersburg on April 25, 26 and 28. The full schedule can be found on www.corpus.ru

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox