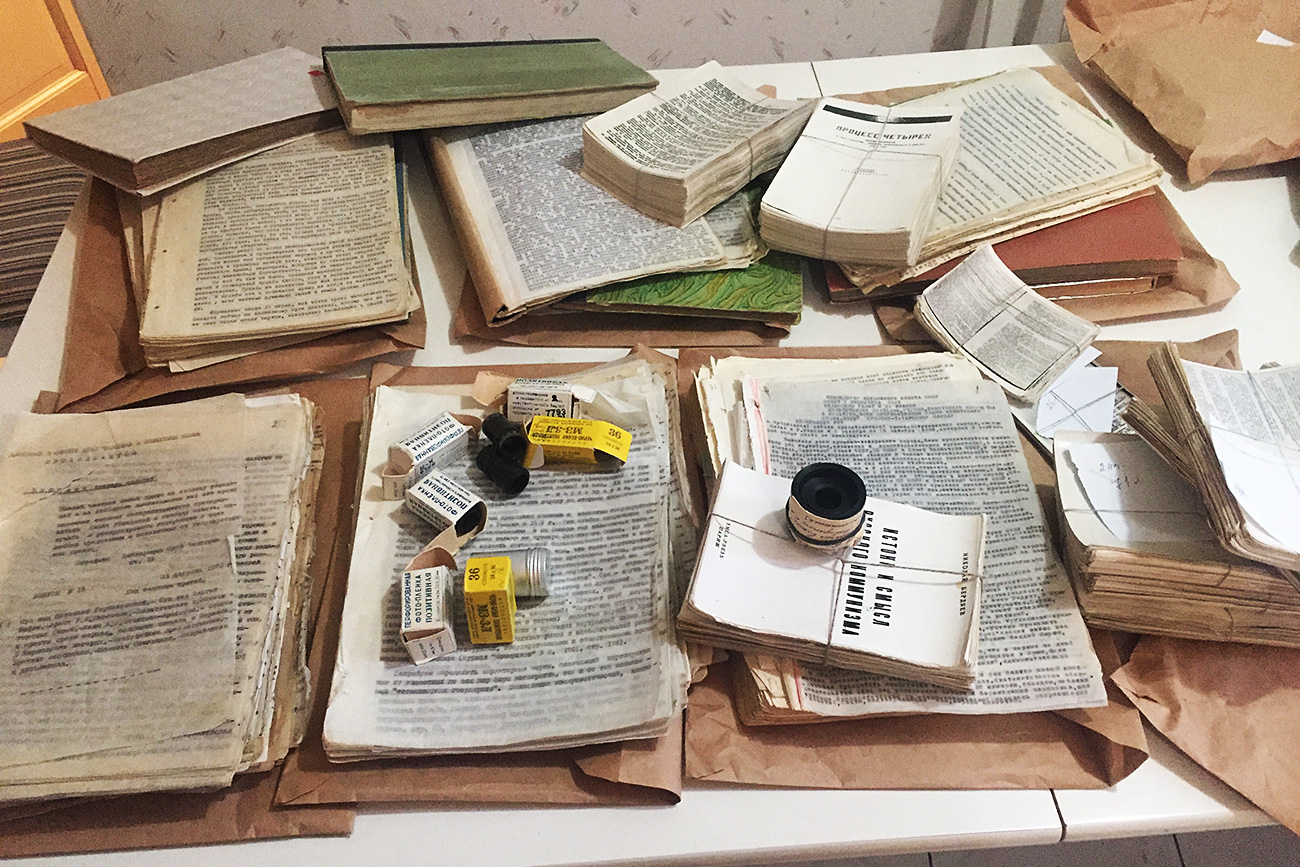

Russian samizdat: photo negatives of unofficial literature / Nkrita (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Russian samizdat: photo negatives of unofficial literature / Nkrita (CC BY-SA 4.0)

What unites the novels Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak, and The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn? Today, they are among the most important books of the 20th century, with millions of copies sold, as well as studied by students in universities on five continents. Soviet readers, however, first saw these classic novels not on shelves in bookstores, but as handmade, 'underground' carbon copies that readers clandestinely passed along to each other. Thanks to samizdat (which literally means "self-published") did works by Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn – and many other novels, poems and songs – gain wide popularity in the Soviet Union.

The USSR always had severe censorship, and the rare period of relaxations, for example, during the Second World War, did not change the overall situation. But while in Stalin's time no one even thought of illegally distributing books and magazines, with the coming of Nikita Khrushchev's 'thaw' and the emergence of the dissident movement the demand for a truthful interpretation of current events and interest in uncensored literature only increased.

In the USSR, the General Directorate for the Protection of State Secrets in the Press (Glavlit) was responsible for censorship, and it carried out preliminary censorship of all books and publications and controlled imported literature. Everything that, in the opinion of the directorate's censors, disparaged the Soviet order or appeared as anti-Soviet propaganda was not published.

The interest in prohibited books and the possibility of reading them after receiving a copy from the author, or from abroad, not only stimulated the development of samizdat but also made it incredibly popular.

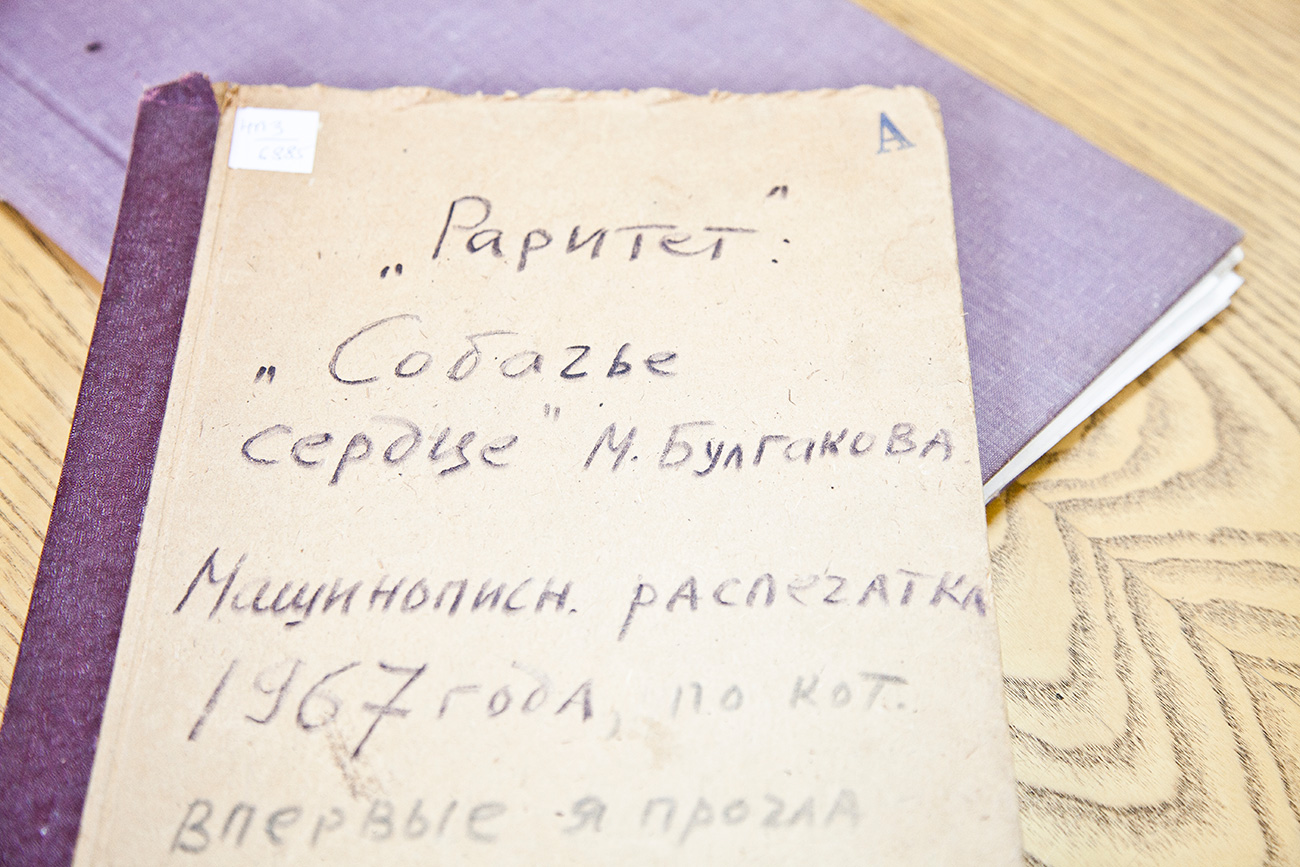

Typed copy of Bulgakov's 'Heart of a Dog' / Kirill Lagutko

Typed copy of Bulgakov's 'Heart of a Dog' / Kirill Lagutko

"My dad and his friends distributed samizdat that they probably got when it came from abroad," remembers Ekaterina Poleschuk. "That's how we read Bukovsky, Solonevich, and Voinovich's Ivan Chonkin… Dad did the bookbinding. I often remember the smell of glue boiling on our stove. He would clamp the photocopied or printed pages, place glue on them and then after some time place them into the cover, which he also made. That's how the samizdat book was produced."

Vladimir Voinovich's novel, The Life and the Unusual Adventures of Soldier Ivan Chonkin was officially published only in 1988, but readers had already familiarized themselves with it much earlier.

"Once dad took the pages of Ivan Chonkin to make the samizdat book, put them in his sports bag and went to work," said Ekaterina. "It was evening. Dad was approached by a policeman and asked to show his ID. Dad always dressed simply, was unshaven, wore a sweater and pants and never carried his ID. That’s why he was taken to the precinct. The policeman searched through his bag and did not release him. Dad was obviously very scared and began thinking how many years he'd get for distributing prohibited literature. He's sitting sadly and watching how the officer on duty is immersed in Chonkin. He read it all night and at daybreak finished reading, sighed, carefully placed the pages back into the bag and shook my dad's hand, wishing him success and advising him to be more cautious in the future."

Exhibition '200 bites in a minute. Typewriter and the mind of the 20th century' and its curator Anna Narinskaya. Source: The Polytechnic Museum

Exhibition '200 bites in a minute. Typewriter and the mind of the 20th century' and its curator Anna Narinskaya. Source: The Polytechnic Museum

Usually, the samizdat works were available as manuscripts and as typewritten copies. Copy paper was used to facilitate the production process. Using a ballpoint pen to manually copy the text on newsprint, copyists could make three clear copies, and if they used a typewriter then as much as five. In the 1970s, there were copies printed with printers, and xeroxed copies with the help of photocopying. Musical works in the beginning were cut with the needle of a homemade phonograph onto old X-rays, and later they were recorded onto a tape recorder and rerecorded until music could be heard through the noise.

Paradoxically, even Nikita Khrushchev's speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which signified the end of Stalin’s personality cult and the beginning of the Thaw, was fully printed and widely distributed on samizdat because Soviet newspapers did not publish it in full.

Dissidents who wanted to attract attention to political issues distributed samizdat magazines. The most famous was The Chronicle of Current Events, which was published with intervals over the course of 15 years because more than half of the managing editors were convicted at one time or another and sent to internal exile. "Tamizdat" ("published there"), which were uncensored works sent abroad for publication and then sent back to the USSR, was also widely distributed among Soviet readers.

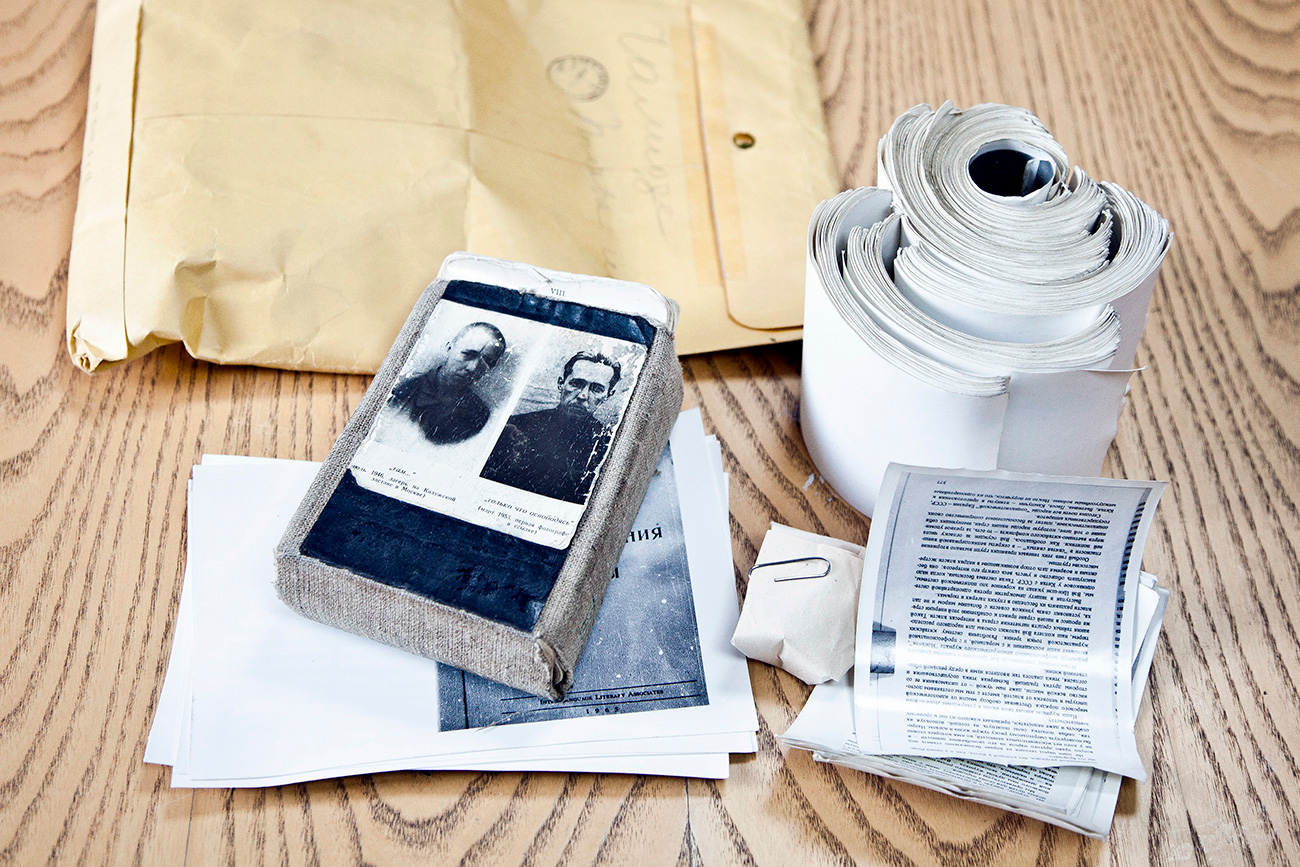

Yuli Daniel (L) and Andrei Sinyavsky on the trial / Archive Photo

Yuli Daniel (L) and Andrei Sinyavsky on the trial / Archive Photo

One of the most infamous tamizdat criminal cases was the trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel, whose stories and novellas were published abroad. The two writers were convicted in accordance with Article 70 of the Criminal Code, "On Anti-Soviet Agitation and Propaganda," which was often used to arrest and convict people for distributing samizdat and tamizdat, although they maintained their innocence. In total, between 1956 and 1987 more than 8,000 people were convicted under this law, as well as Article 190-1, "On The Distribution of Deliberately False Fabrications Defaming The Soviet Order."

Thanks to samizdat, Soviet readers not only gained access to forbidden novels and novellas and had the chance to learn about political issues, but they also read the Silver Age poets for the first time, because many of them were also banned in the USSR or simply not published by the state-owned publishing companies.

Samizdat copies / Kirill Lagutko

Samizdat copies / Kirill Lagutko

"We republished Tsvetaeva by hand, bound the pages together and gave it to others to read," remembers Mikhail Seregin. Samizdat was designed not only for the printed word - musical notes were also prepared by hand.

"We printed the musical lines with a typewriter and wrote the notes and signs by hand. Then we copied the pages and sewed them together," explained Seregin. That’s how poems and songs by bards Bulat Okudzhava, Yuri Vizbor and others were distributed.

In the 1970s-1980s, not only dissidents busied themselves with samizdat, but it was also distributed among students and lovers of fine literature and music. Bulgakov, Tolkien, Akhmatova and Vysotsky are just a few of the names on the sundry list of authors that samizdat made accessible to the public.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox