Dneprovsky is one of the few extant camps of the Kolyma Gulag. From 1941 to 1955 there was a pit tin mine where ordinary prisoners, "especially dangerous criminals" and former Soviet POWs labored.

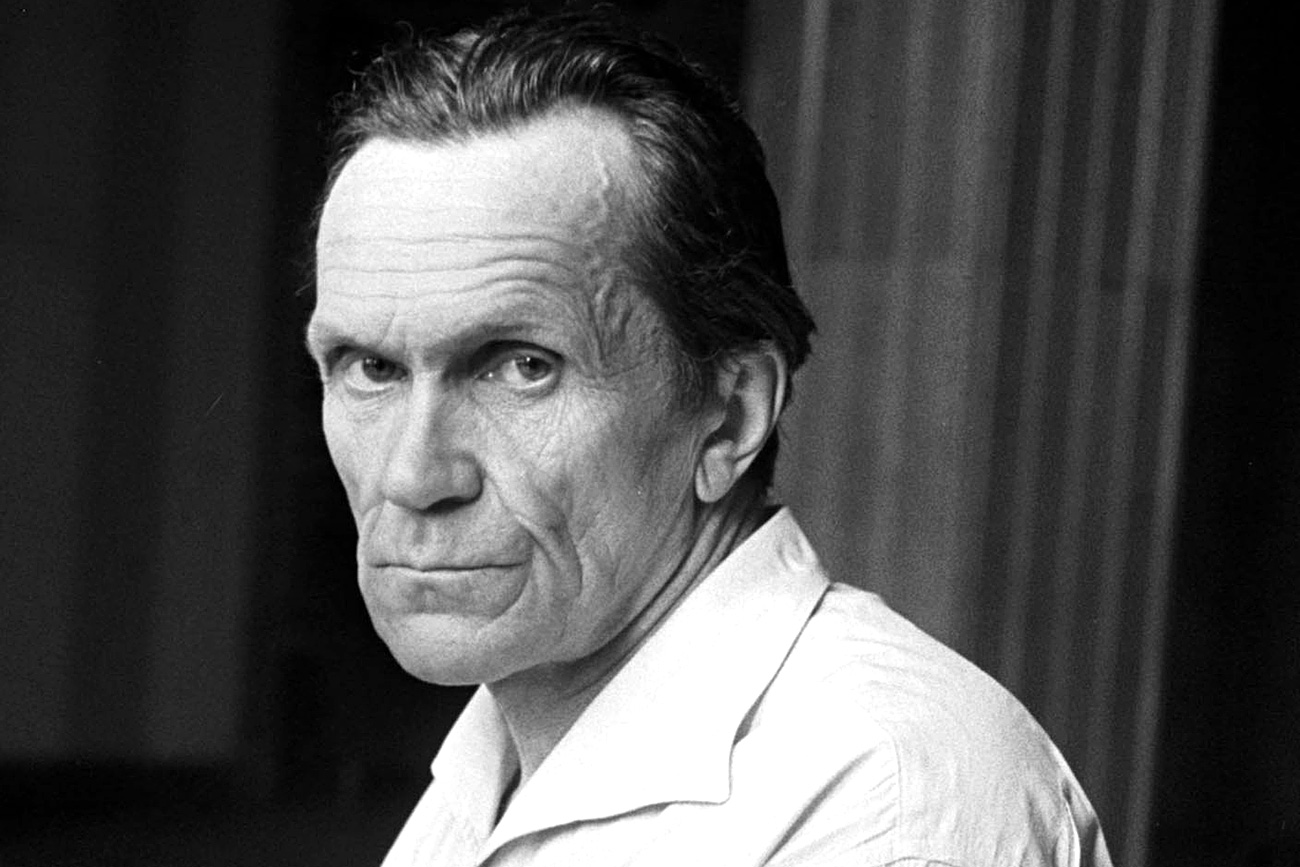

Emil Gataullin Varlam Shalamov / A.Less/TASS

Varlam Shalamov / A.Less/TASS

Varlam Shalamov, who wrote the collection of short stories, Kolyma Tales, over the course of 20 years, also seemed to predict the rise of bloggers. He wrote: “People with different jobs that have a talent for writing, not professional writers, will start speaking out.”

He expected that believability and reliability would become the sources of real power for literature in the future. That is why his stories are full of unbiased observations from his days in the labor camp. These particular stories are clear and concise in their documentation of the experience of the Soviet gulag and are more striking and harrowing than any frightening fiction.

"But the cold kept up, and Potashnikov knew he couldn’t hold out any longer. Breakfast sustained his strength for no more than an hour of work, and then exhaustion ensued. Frost penetrated the body to the ‘marrow of the bone’ — the phrase was no metaphor. A man could wave his pick or shovel, jump up and down so as not to freeze — till dinner. Dinner was hot — a thin broth and two spoons of kasha that restored one’s strength only a little but nevertheless provided some warmth. And then there was strength to work for an hour, and after that Potashnikov again felt himself in the grip of the cold. The day would finally come to a close, and after supper all the workers would take their bread back to the barracks, where they would eat it, washing it down with a mug of hot water. Not a single man would eat his bread in the mess hall with his soup. After that Potashnikov would go to sleep.

He slept, of course, on one of the upper berths, because the lower ones were like an ice cellar. Everyone who had a lower berth would stand half the night at the stove, taking turns with his neighbors in embracing it; the stove retained a slight remnant of warmth. There was never enough firewood, because to go for it meant a four-kilometer walk after work and everyone avoided the task. The upper berths were warmer, but even so everyone slept in his working clothes — hats, padded coats, pea jackets, felt pants. Even with the extra warmth, by the morning a man’s hair would be frozen to the pillow.

Potashnikov felt his strength leaving him every day. A thirty-year-old man, he had difficulty in climbing on to an upper berth and even in getting down from it. His neighbor had died yesterday. The man simply didn’t wake up, and no one asked for the cause of death, as if there were only one cause that everyone knew."

“Are you a doctor?” asked Bagretsov, sucking the wound.

Glebov remained silent. The time when he had been a doctor seemed very far away. Had it ever existed? Too often the world beyond the mountains and seas seemed unreal, like something out of a dream. Real were the minute, the hour, the day — from reveille to the end of work. He never guessed further, nor did he have the strength to guess. Nor did anyone else.

He didn’t know the past of the people who surrounded him and didn’t want to know. But then, if tomorrow Bagretsov were to declare himself a doctor of philosophy or a marshal of aviation, Glebov would believe him without a second thought. Had he himself really been a doctor? Not only the habit of judgment was lost, but even the habit of observation. Glebov watched Bagretsov suck the blood from his finger but said nothing. The circumstance slid across his consciousness, but he couldn’t find or even seek within himself the will to answer.

Dneprovsky is one of the few extant camps of the Kolyma Gulag. From 1941 to 1955 there was a pit tin mine where ordinary prisoners, "especially dangerous criminals" and former Soviet POWs labored / Emil Gataullin

Dneprovsky is one of the few extant camps of the Kolyma Gulag. From 1941 to 1955 there was a pit tin mine where ordinary prisoners, "especially dangerous criminals" and former Soviet POWs labored / Emil Gataullin

We tried to work, but our lives were too distant from anything that could be expressed in figures, wheelbarrows, or percent of plan. The figures were a mockery. But for an hour, for one moment after that night’s dinner, we got our strength back.

And suddenly I realized that that night’s dinner had given the sectarian the strength he needed for his suicide. He needed that extra portion of kasha to make up his mind to die. There are times when a man has to hurry so as not to lose his will to die.

As usual, we encircled the stove. But today there was no one to sing any hymns. And I guess I was even happy that it was finally quiet.

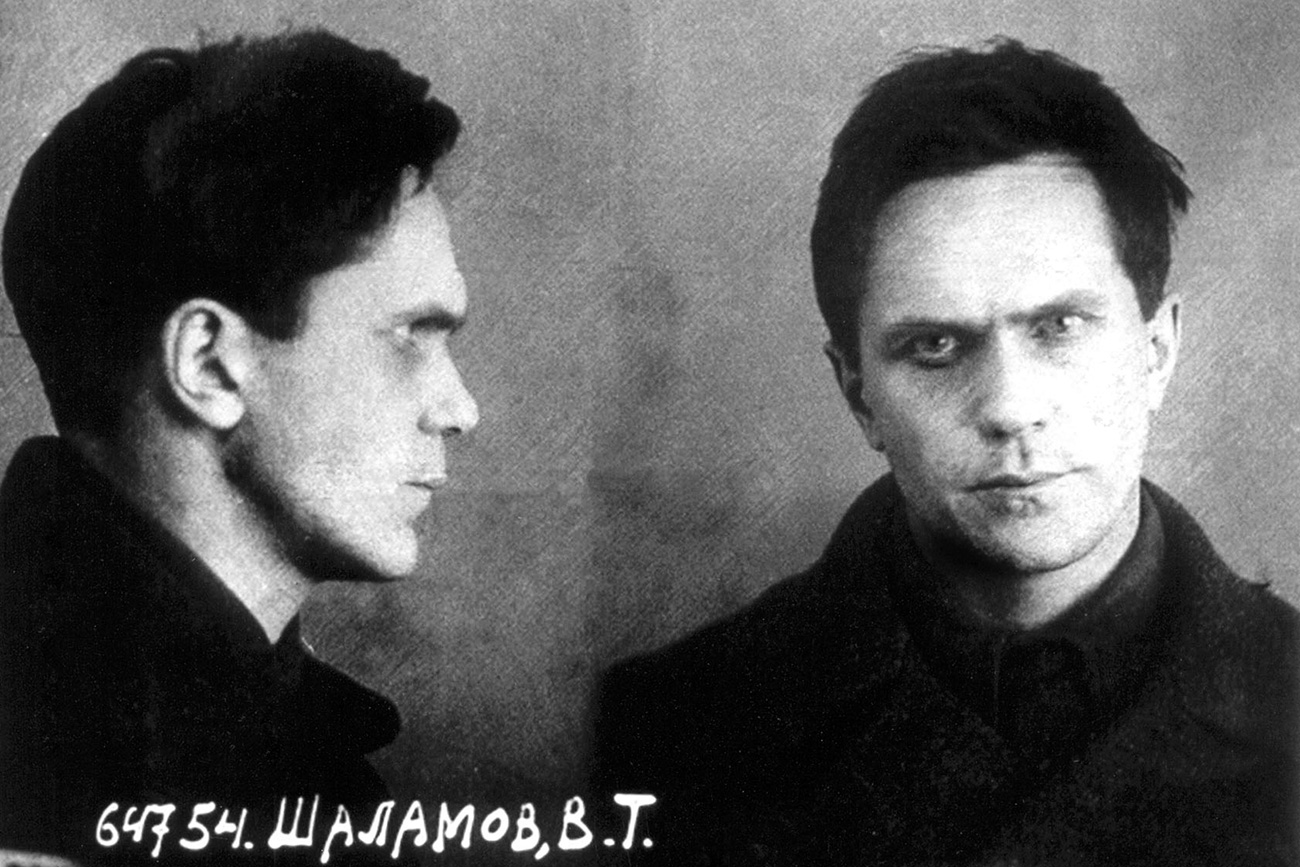

Official NKVD photo from Varlam Shalamow personal file after arrest, 1937 / Archive Photo

Official NKVD photo from Varlam Shalamow personal file after arrest, 1937 / Archive Photo

We were all tired of barracks food. Each time they brought in the soup in large zinc tubs suspended on poles, it made us all want to cry. We were ready to cry for fear that the soup would be thin. And when a miracle occurred and the soup was thick, we couldn’t believe it and ate it as slowly as possible. But even with thick soup in a warm stomach there remained a sucking pain; we’d been hungry for too long. All human emotions — love, friendship, envy, concern for one’s fellow man, compassion, longing for fame, honesty — had left us with the flesh that had melted from our bodies during their long fasts.

“Just imagine,” said Savelev. “We’ll survive, leave for the mainland, and quickly become sick old men. We’ll have heart pains and rheumatism, and all the sleepless nights, the hunger, and long hard work of our youth will leave their mark on us even if we remain alive. We’ll be sick without knowing why, groan and drag ourselves from one dispensary to another. This unbearable work will leave us with wounds that can’t be healed, and all our later years will lead to lives of physical and psychological pain. And that pain will be endless and assume many different forms. But even among those terrible future days there will be good ones when we’ll be almost healthy and we won’t think about our sufferings. And the number of those days will be exactly equal to the number of days each of us has been able to loaf in camp.”

That's how Kolyma looks today, more than half a century after Shalamov / Emil Gataullin

That's how Kolyma looks today, more than half a century after Shalamov / Emil Gataullin

We finished the work, stacked the wood, and waited for the guards. Our guard was keeping warm in the building for which we’d been chopping wood, but we were supposed to march back in formation, breaking up in town into smaller groups.

We didn’t go to warm up, though, since we had long since noticed, next to a fence, a large heap of garbage — something we could not afford to ignore. Both my companions were soon removing one frozen layer after another with the adroitness that comes from practice. Their booty consisted of lumps of frozen bread, an icy piece of hamburger, and a torn pair of men’s socks. The socks were the most valuable item, of course, and I regretted that I hadn’t found them first. “Civvies” — socks, scarves, gloves, shirts, pants — were prized by people who for decades had nothing to wear but convict garb. The socks could be darned and exchanged for tobacco or bread.

The evil acts committed by criminals in camp are innumerable. The unfortunates are those from whom the thief steals their last rags, confiscates their last coin. The working man is afraid to complain, for he sees that the criminals are stronger than the camp authorities. The thief beats the working man and forces him to work. Tens of thousands of people have been beaten to death by thieves. Hundreds of thousands of people who have been in the camps are permanently seduced by the ideology of these criminals and have ceased to be people. Something criminal has entered into their souls for ever. Thieves and their morality have left an indelible mark on the soul of each.

Following the footsteps of Varlam Shalamov: The frozen valley of Myakit river / Emil Gataullin

Following the footsteps of Varlam Shalamov: The frozen valley of Myakit river / Emil Gataullin

The camp administrator is rude and cruel; the persons responsible for propaganda lie; the doctor has no conscience. But all this is trivial in comparison with the corrupting power of the criminal world. In spite of everything, the authorities are still human beings, and the human element in them does survive. The criminals are not human.

The influence of their morality on camp life is boundless and many-sided. The camps are in every way schools of the negative. No one will ever receive anything useful or necessary from them — neither the convict himself, nor his superiors, nor the guard, nor the inadvertent witnesses (engineers, geologists, doctors), nor the camp administrators, nor their subordinates.

Every minute of camp life is a poisoned minute.

Original stories copyright © Iraida Pavlovna Sirorinskaya, 1980. Translation copyright © John Glad, 1980, 1981, 1994, Penguin Books

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox