The key moments in Russian literary works can easily be reimagined with the addition of the type of text messages that are sent by mobile banking services. The characters are often in debt, running from their creditors and seem like they would have a hard time surviving in the modern world.

Illustration of Gogol's 'Dead Souls,' Chichikov (L) visits Plyushkin / Getty Images

Illustration of Gogol's 'Dead Souls,' Chichikov (L) visits Plyushkin / Getty Images

Doctors, speculators and the unfortunate victims of lies and dubious commercial propositions — Russia's literary classics are full of protagonists who are burdened by financial obligations.

If these characters were around today, they would easily become the daily target of banks and debt collectors. Looking at the classics, if we remove the profound philosophical undertones, we will find that the plots are just about normal people burdened by debt or living in a rented apartment they can no longer afford.

RBTH imagines the kind of messages that would be filling up these characters phones. It turns out that the text messages from banks can be an ideal way to explore the famous characters' sufferings and triumphs. But be careful! If you have not read these books you should know that this article contains spoilers.

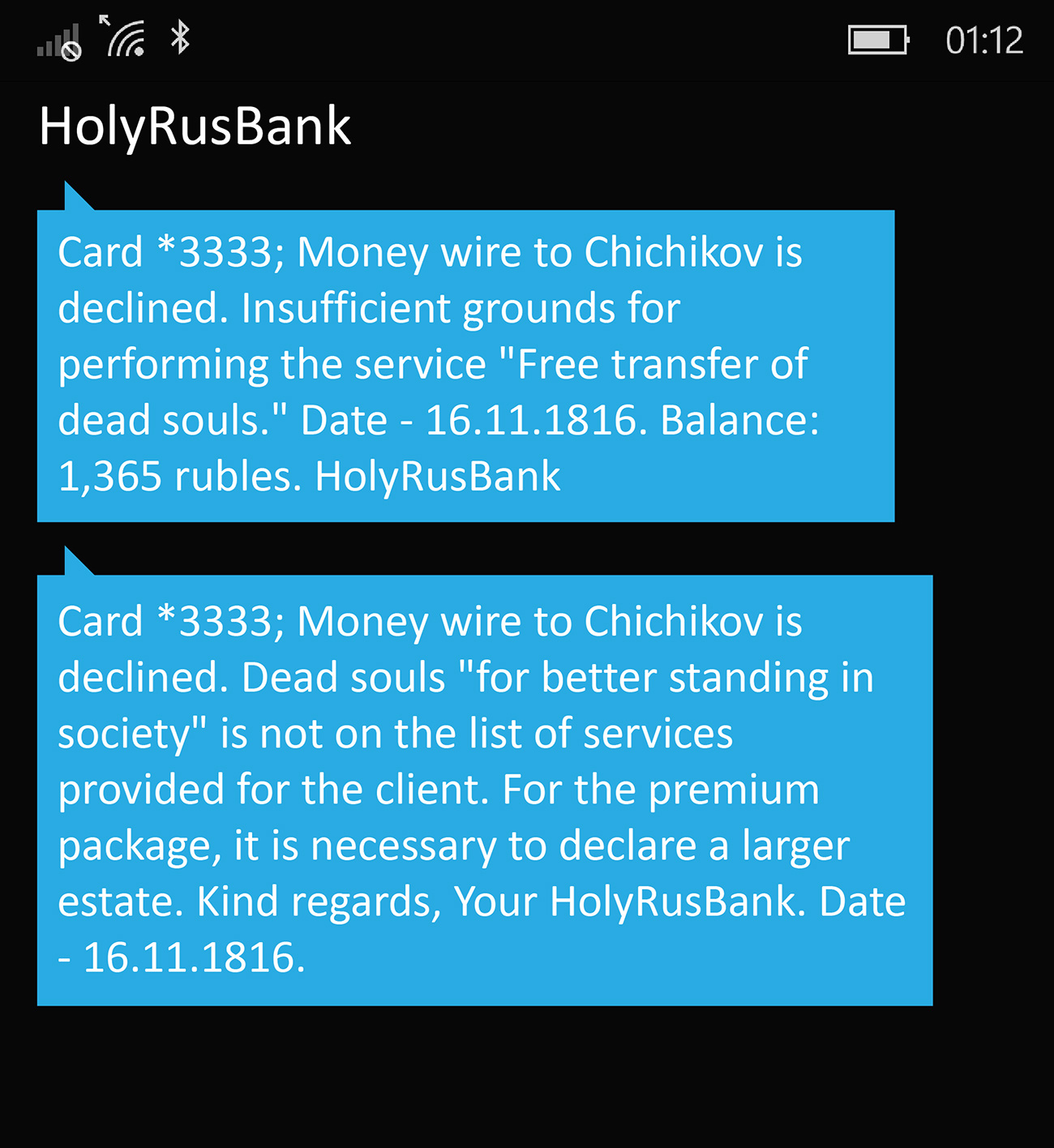

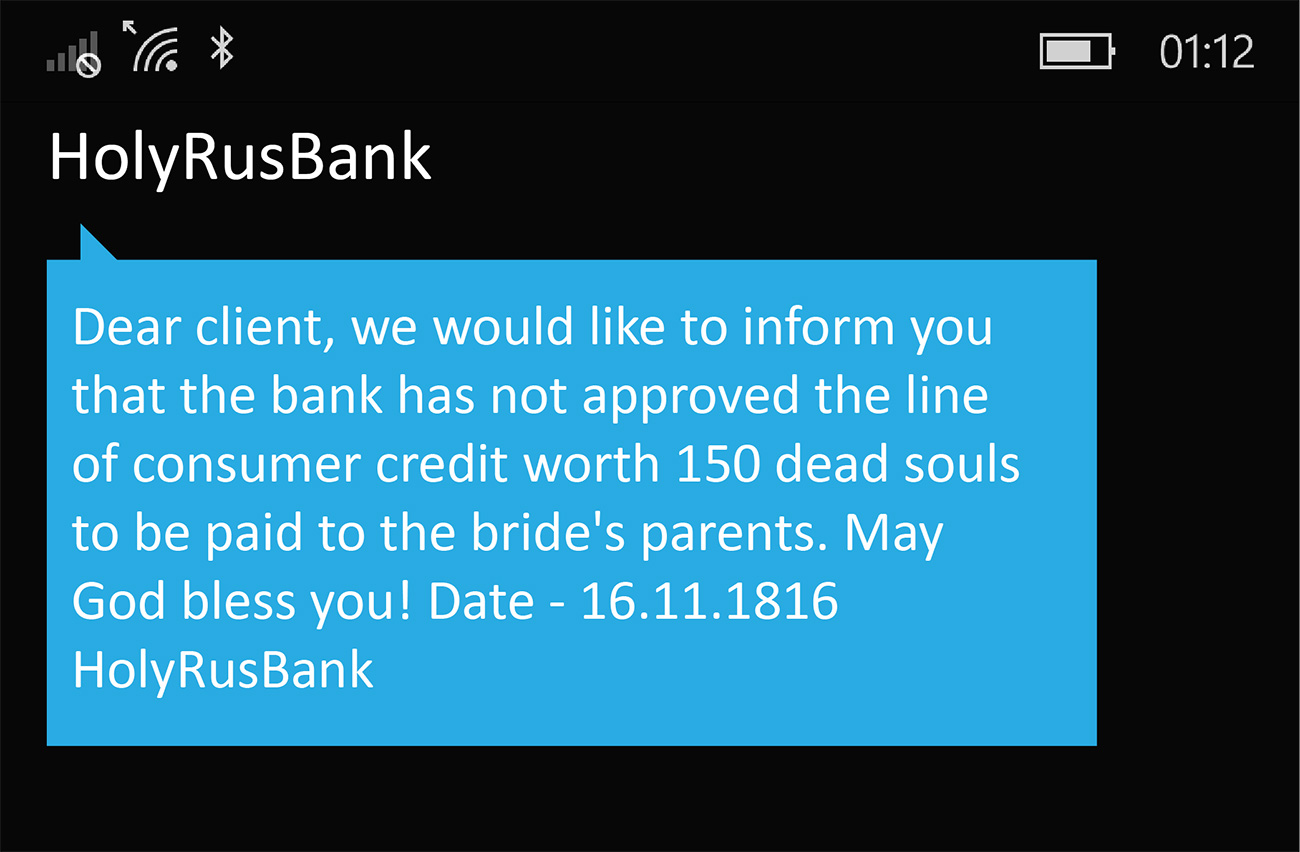

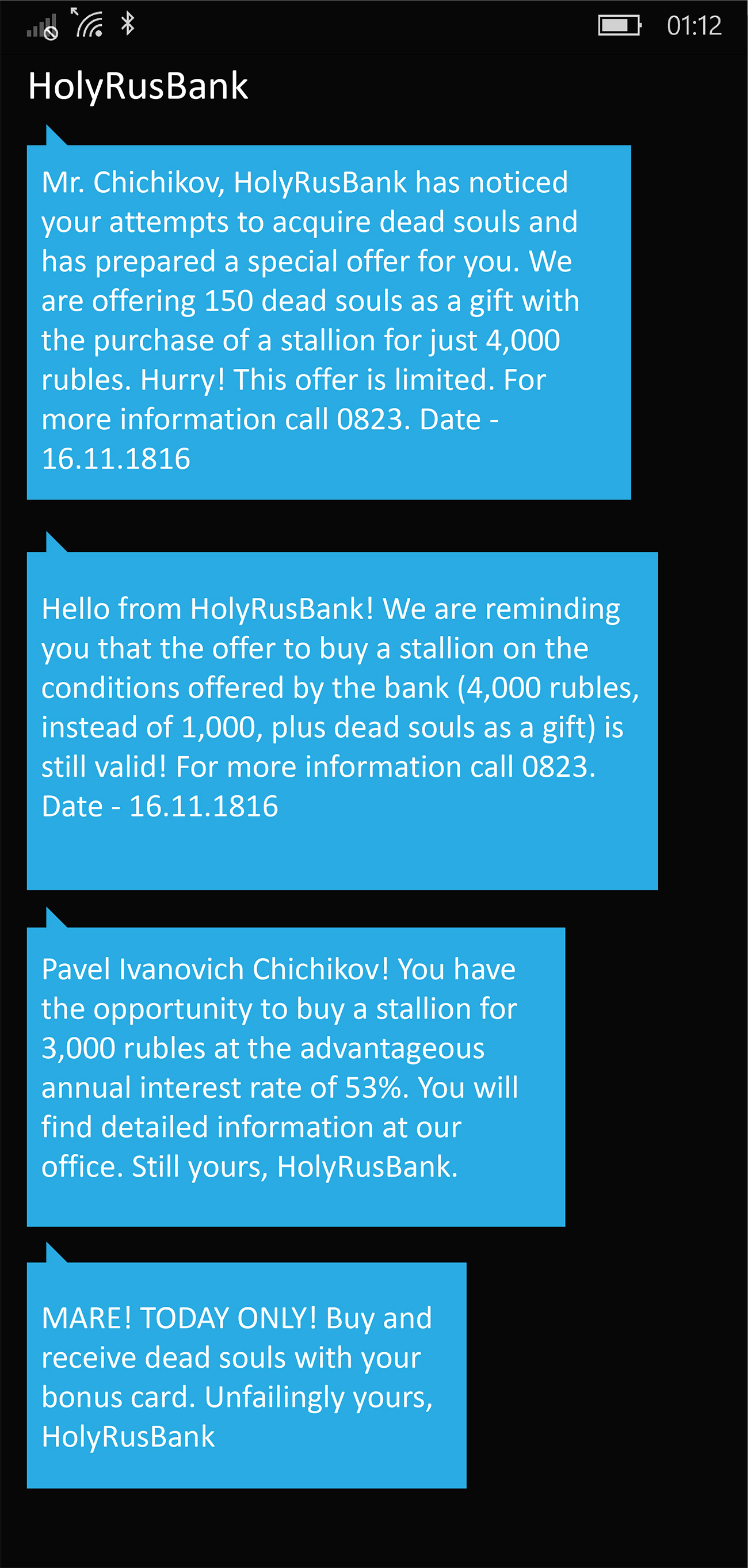

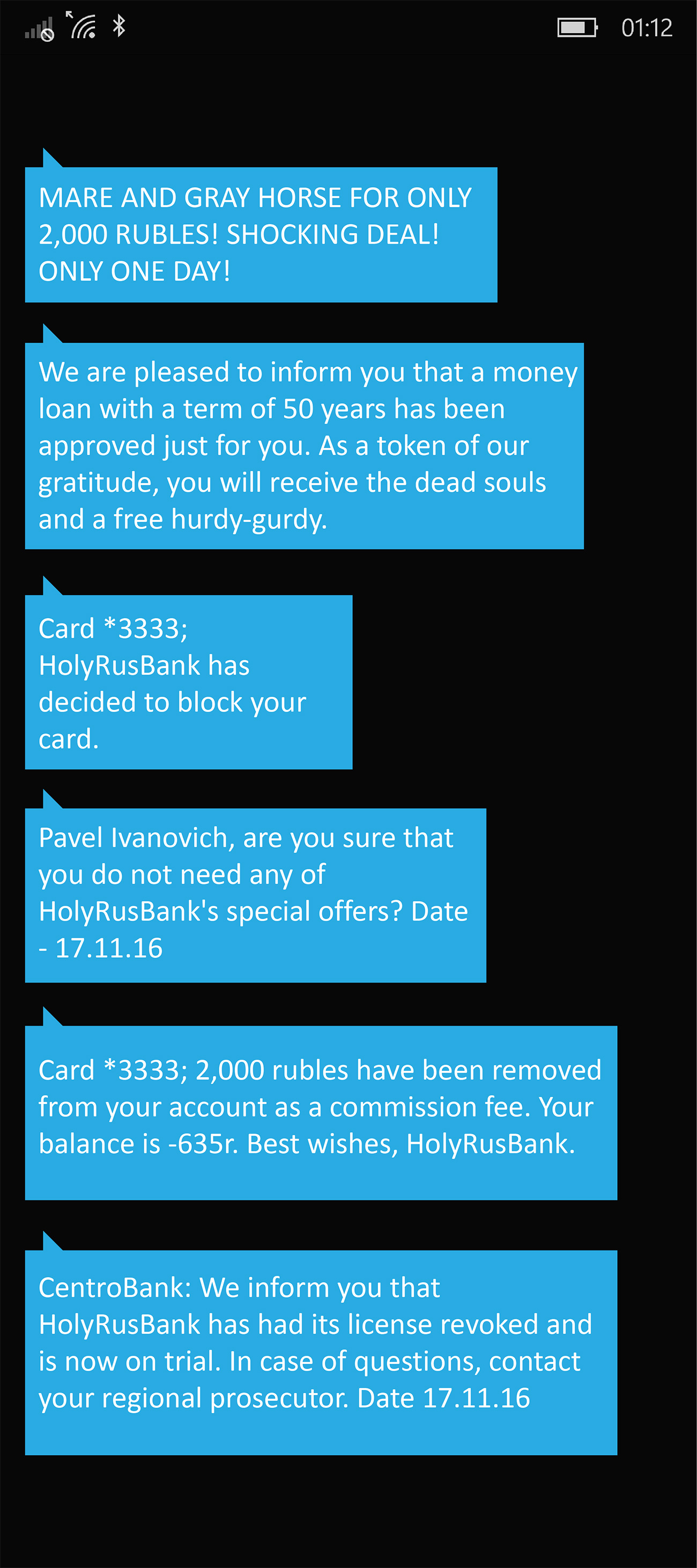

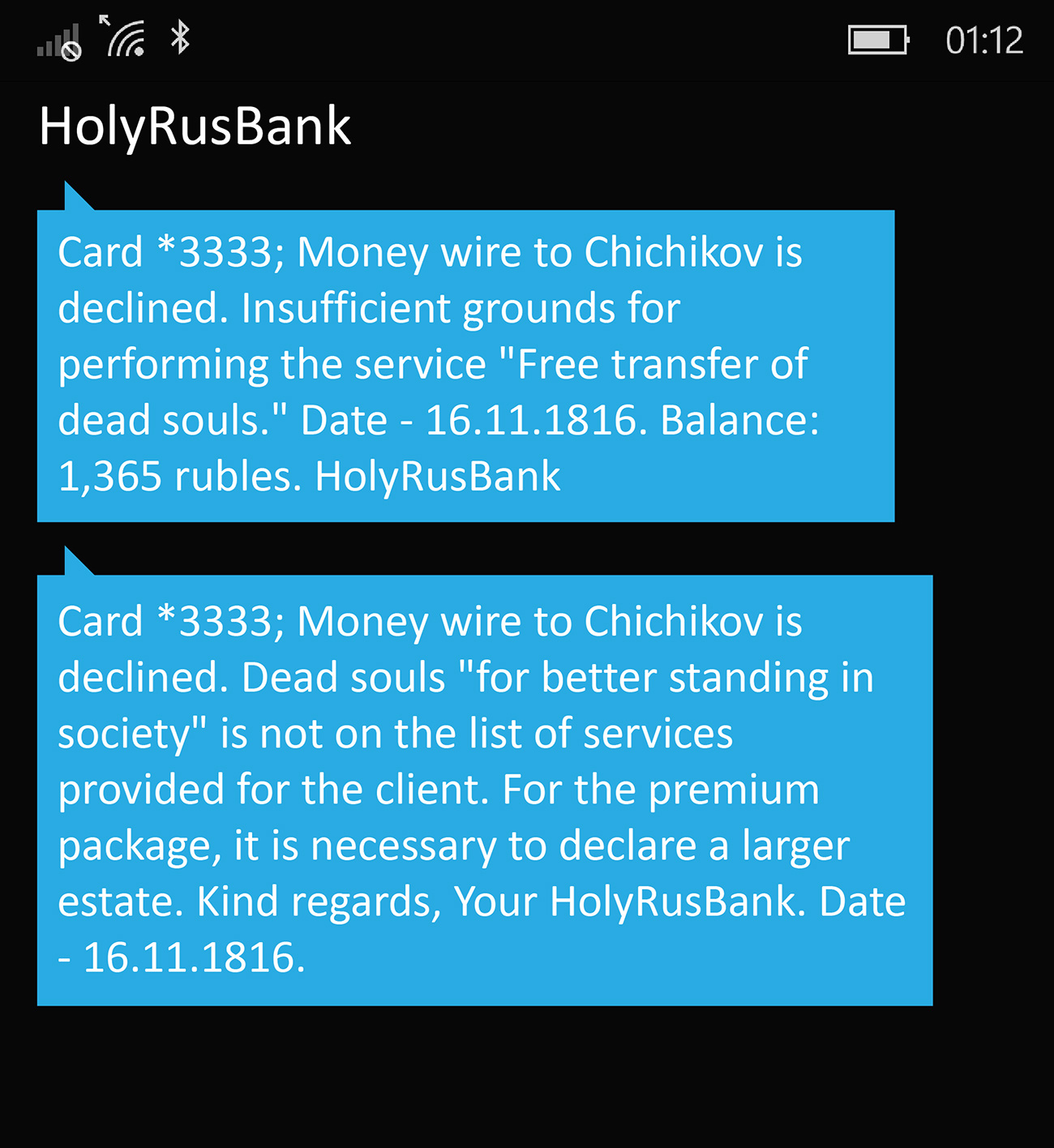

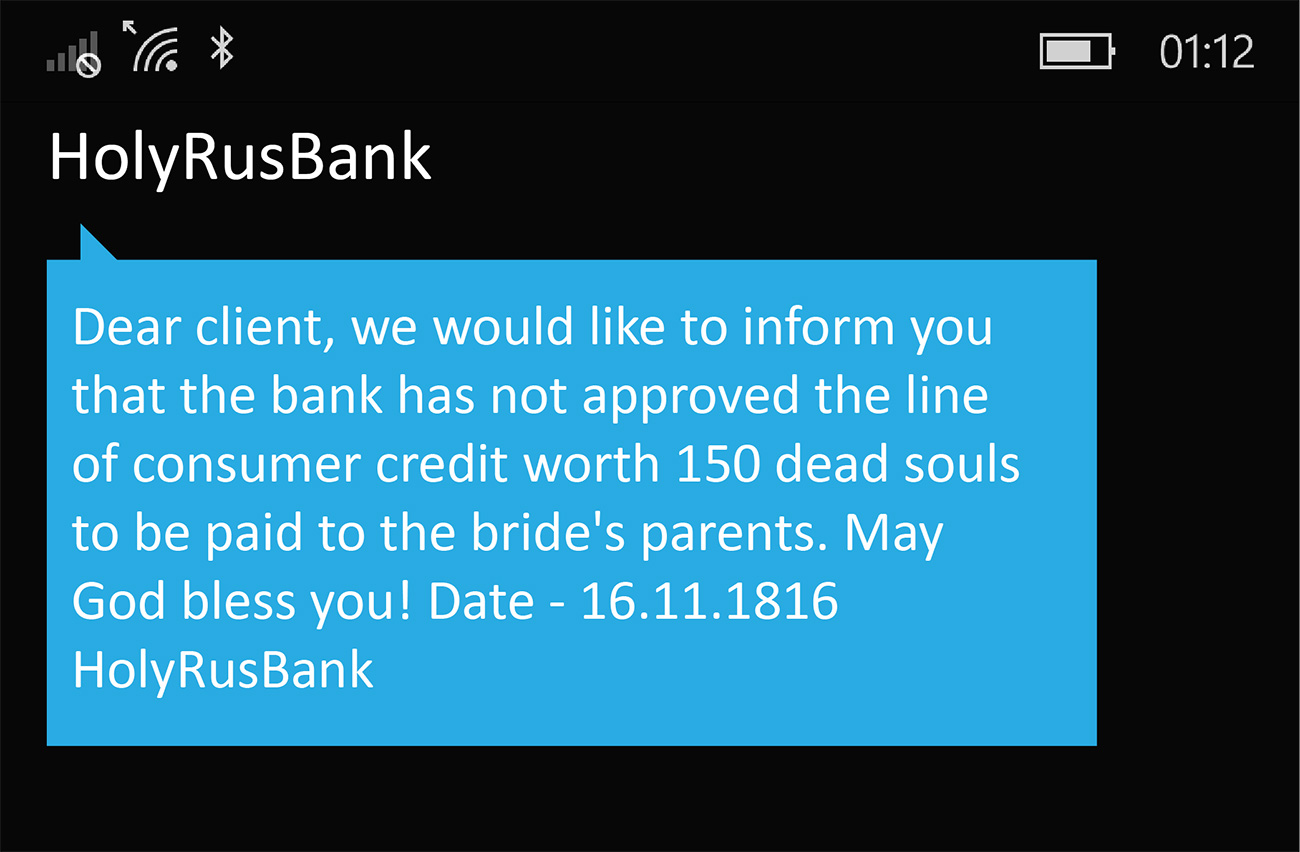

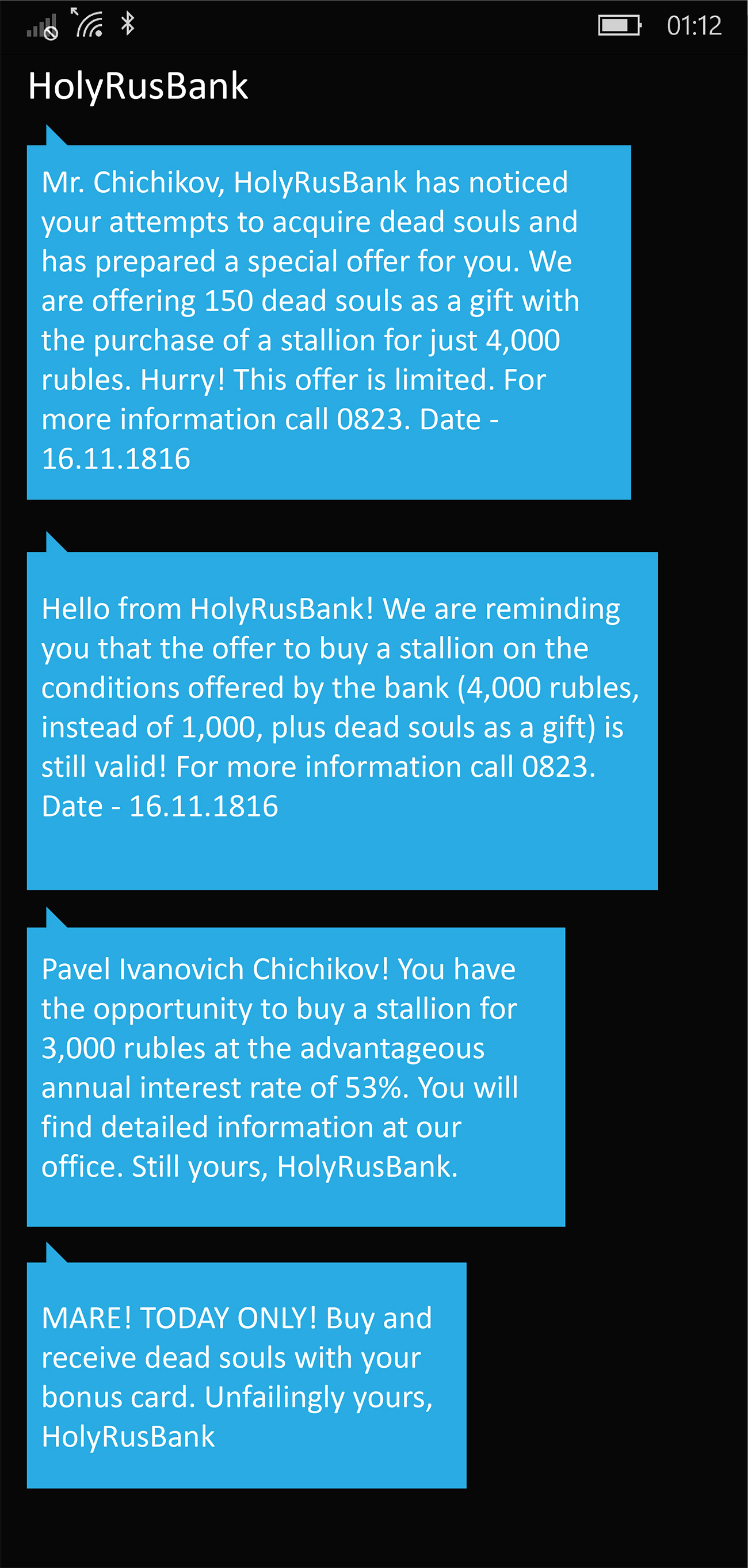

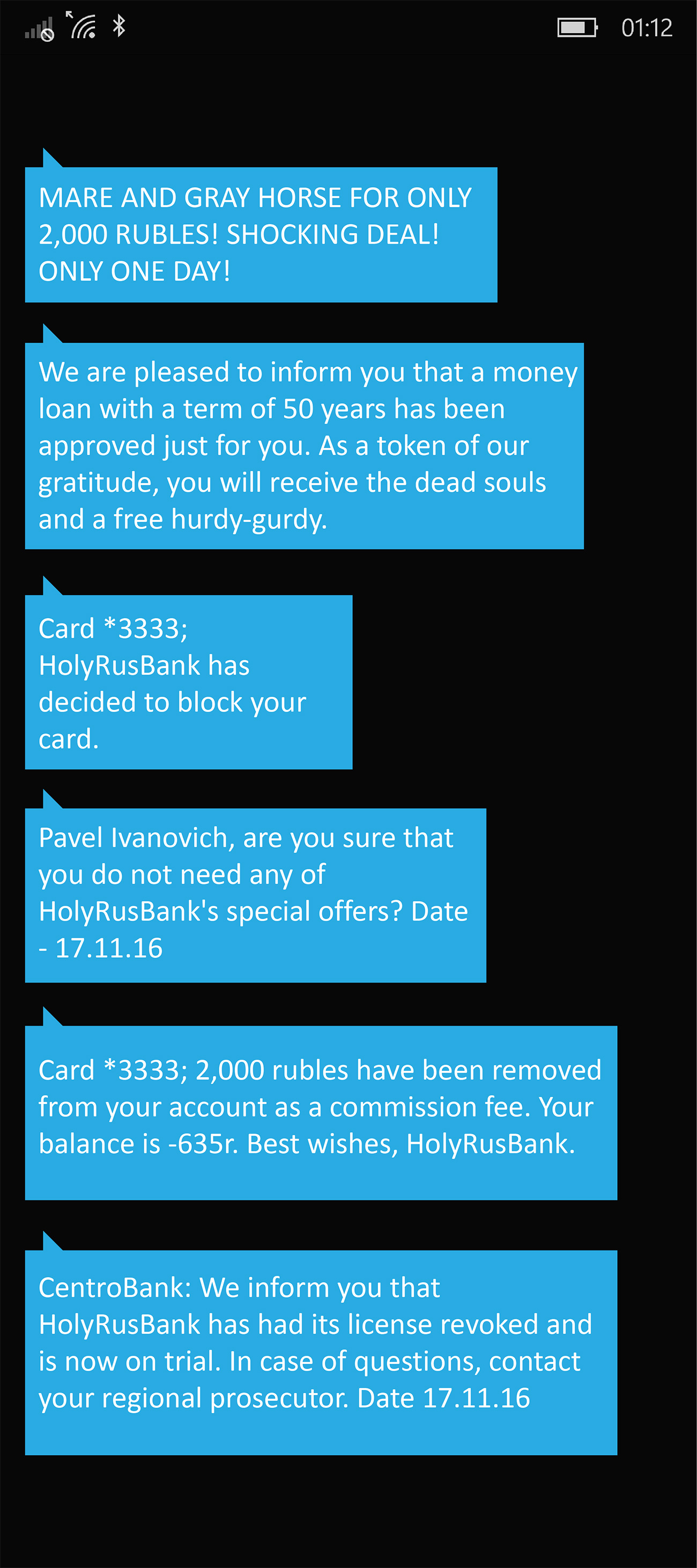

Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol: The story of an annoying unlicensed bank

This is a masterpiece poem, written in prose, about human cunning and mortal sins. Collegiate counselor Pavel Ivanovich Chichikov travels the country, buying up serfs' "dead souls" (they have died but have not yet been removed from the official records) at a low price. During his adventures, he interacts with a few banks.

His transactions for buying the "souls" are blocked and payments are delayed or do not arrive in their entirety. Basically, the whole buying and selling process is tormenting and annoying to everyone involved. The essence of one of the episodes (Chapter IV) is as follows:

Extract from the book:

“This, then, is my request. I presume that you have a large number of dead serfs whose names have not yet been removed from the revision list?”“I have. But why do you ask?”“Because I want you to make them over to me.”“Of what use would they be to you?”“Never mind. I have a purpose in wanting them.”“What purpose?”“A purpose which is strictly my own affair. In short, I need them.”“You seem to have hatched a very fine scheme. Out with it, now! What is in the wind?”“How could I have hatched such a scheme as you say? One could not very well hatch a scheme out of such a trifle as this.”“Then for what purpose do you want the serfs?”“Oh, the curiosity of the man! He wants to poke his fingers into and smell over every detail!”“Why do you decline to say what is in your mind? At all events, until you DO say I shall not move in the matter.”“But how would it benefit you to know what my plans are? A whim has seized me. That is all. Nor are you playing fair. You have given me your word of honor, yet now you are trying to back out of it.”“No matter what you desire me to do, I decline to do it until you have told me your purpose.”“What am I to say to the fellow?” thought Chichikov. He reflected for a moment, and then explained that he wanted the dead souls in order to acquire a better standing in society, since at present he possessed little landed property, and only a handful of serfs.“You are lying,” said Nozdrev without even letting him finish. “Yes, you are lying my good friend.”

Extract from the book:

“Should I tell you the truth,” he added aloud, “I must beg of you not to repeat it. The truth is that I am thinking of getting married. But, unfortunately, my betrothed’s father and mother are very ambitious people, and do not want me to marry her, since they desire the bridegroom to own not less than three hundred souls, whereas I own but a hundred and fifty, and that number is not sufficient.”

Extract from the book:

However, after a pause he added:“If you do not care to give me the serfs, why not SELL them?”“SELL them? I know you, you rascal! You wouldn’t give me very much for them, WOULD you?”“A nice fellow! Look here. What are they to you? So many diamonds, eh?”“I thought so! I know you!”“Pardon me, but I could wish that you were a member of the Jewish persuasion. You would give them to me fast enough then.”“On the contrary, to show you that I am not a usurer, I will decline to ask of you a single kopeck for the serfs. All that you need do is to buy that colt of mine, and then I will throw in the serfs in addition.”“But what should I want with your colt?” said Chichikov, genuinely astonished at the proposal.“What should YOU want with him? Why, I have bought him for ten thousand rubles, and am ready to let you have him for four.”“I ask you again: of what use could the colt possibly be to me? I am not the keeper of a breeding establishment.”“Ah! I see that you fail to understand me. Let me suggest that you pay down at once three thousand rubles of the purchase money, and leave the other thousand until later.”“But I do not mean to buy the colt, damn him!”“Then buy the roan mare.”“No, nor the roan mare.”“Then you shall have both the mare and the grey horse which you have seen in my stables for two thousand rubles.”

Extract from the book:

“Kindly tell me which of you is Monsieur Nozdrev?” said the unknown with a glance of perplexity both at the person named (who was still standing with pipe-shank upraised) and at Chichikov (who was just beginning to recover from his unpleasant predicament).“Kindly tell ME whom I have the honor of addressing?” retorted Nozdrev as he approached the official.“I am the Superintendent of Rural Police.”“And what do you want?”“I have come to fulfill a commission imposed upon me. That is to say, I have come to place you under arrest until your case shall have been decided.”“Rubbish! What case, pray?”“The case in which you involved yourself when, in a drunken condition, and through the instrumentality of a walking-stick, you offered grave offence to the person of Landowner Maksimov.”“You lie! To your face I tell you that never in my life have I set eyes upon Landowner Maksimov.”“Good sir, allow me to represent to you that I am a Government officer. Speeches like that you may address to your servants, but not to me.”

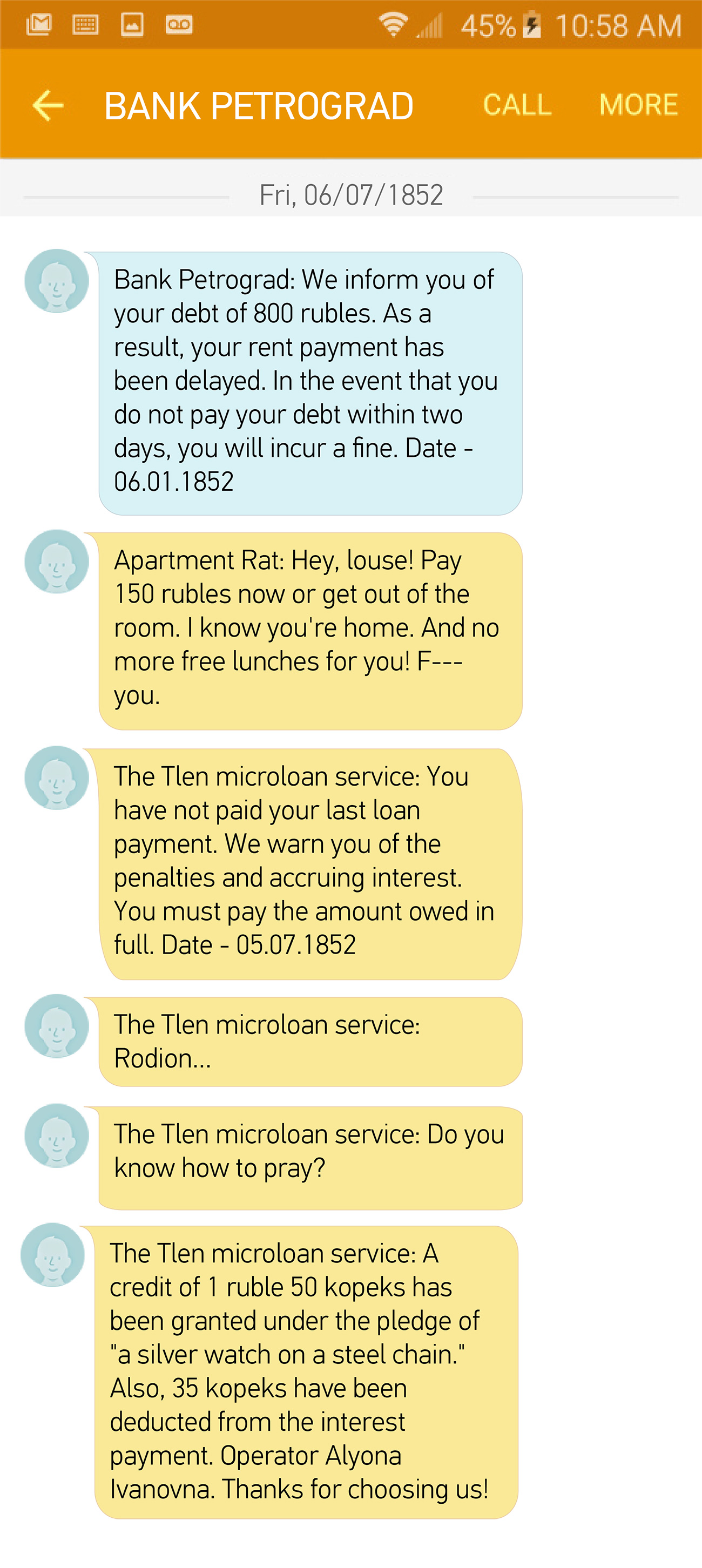

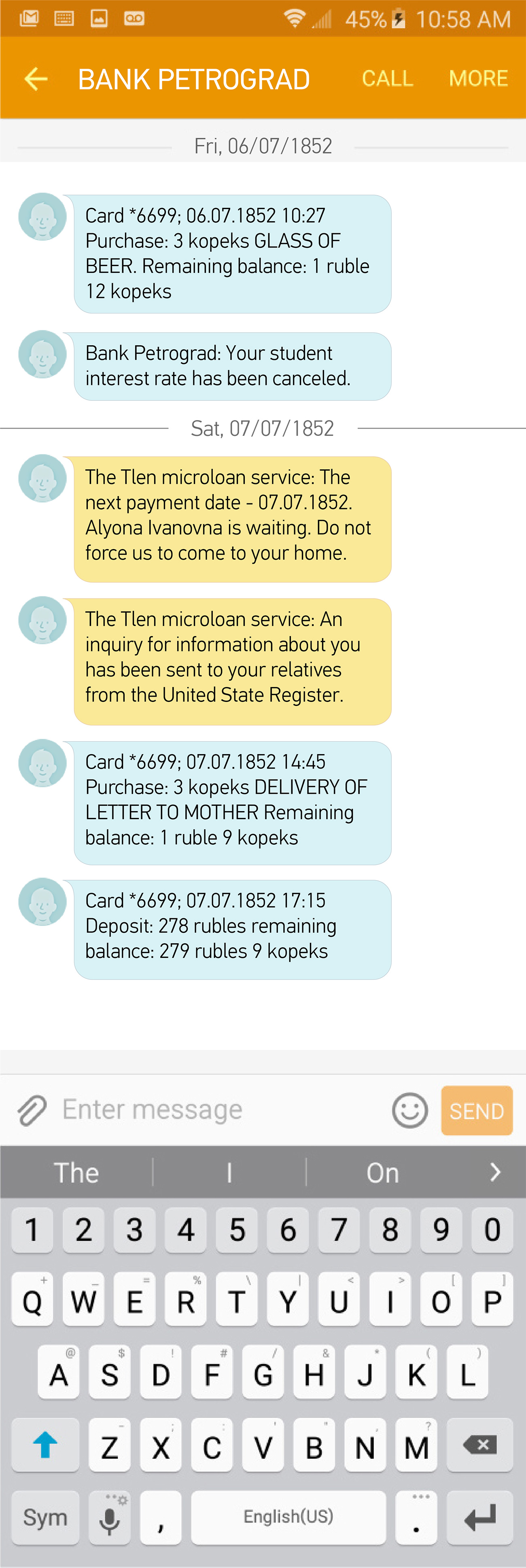

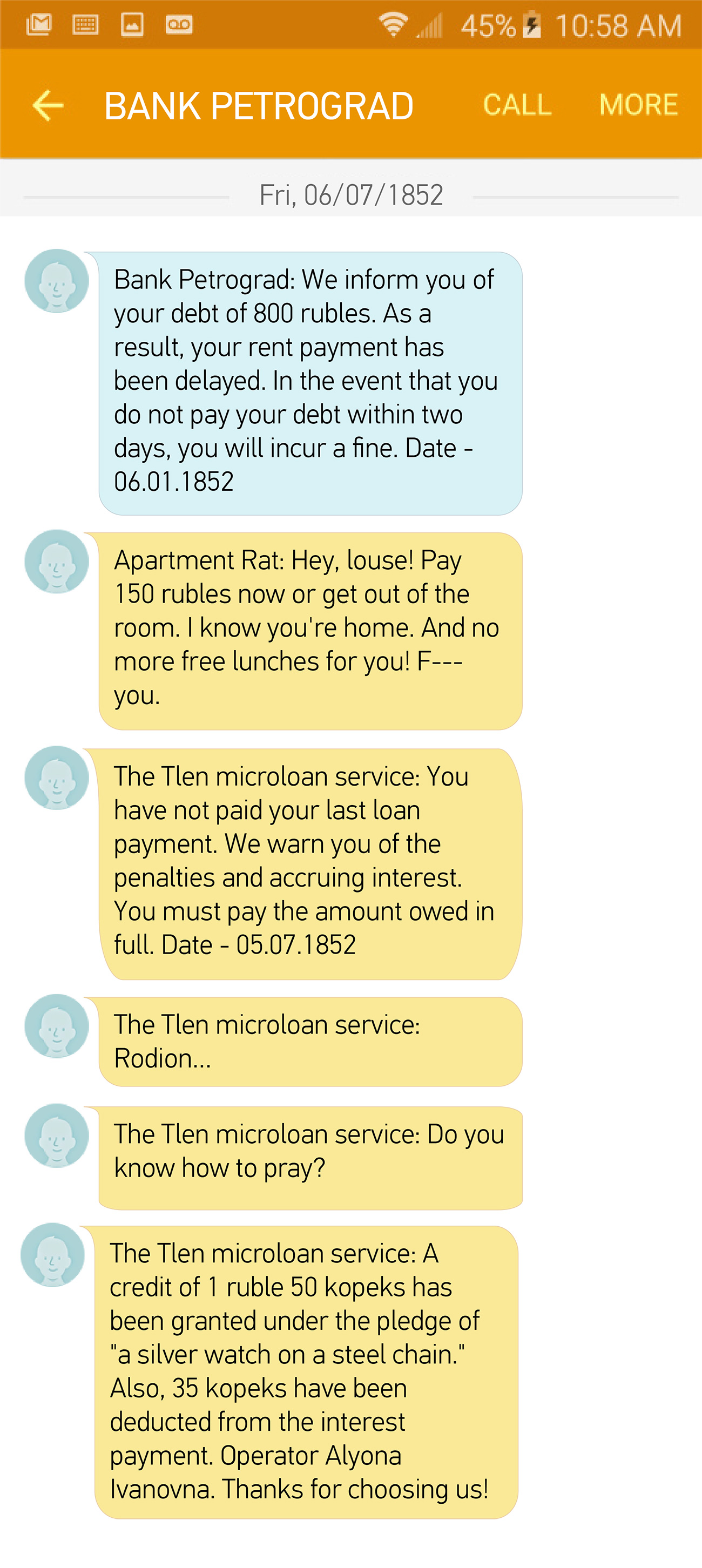

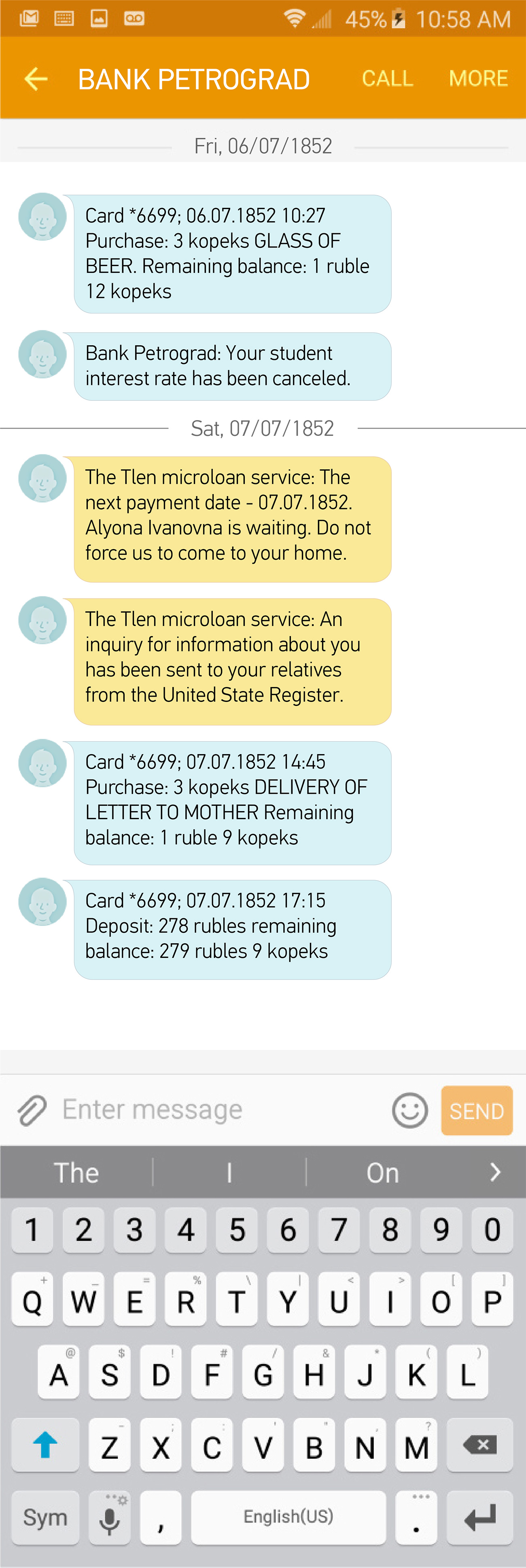

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky: A tale of late rent payments and microloans

On a hot July day, the impoverished failed student Rodion Raskolnikov decides to commit one of the most famous crimes in the world of literature: he uses an axe to cut off the heads of an old pawnbroker and her sister, Elizaveta, and then robs them.

Before carrying out the murders, Raskolnikov had been wallowing in the depths of financial misery and had reached rock bottom.

Extract from the book:

“What do you want?” the old woman said severely, coming into the room and, as before, standing in front of him so as to look him straight in the face.“I’ve brought something to pawn here,” and he drew out of his pocket an old-fashioned flat silver watch, on the back of which was engraved a globe; the chain was of steel.“But the time is up for your last pledge. The month was up the day before yesterday.”“I will bring you the interest for another month; wait a little.”“But that’s for me to do as I please, my good sir, to wait or to sell your pledge at once.”“How much will you give me for the watch, Alyona Ivanovna?”“You come with such trifles, my good sir, it’s scarcely worth anything. I gave you two rubles last time for your ring and one could buy it quite new at a jeweler’s for a ruble and a half.”“Give me four rubles for it, I shall redeem it, it was my father’s. I shall be getting some money soon.”“A ruble and a half, and interest in advance, if you like!”“A ruble and a half!” cried the young man.

Extract from the book:

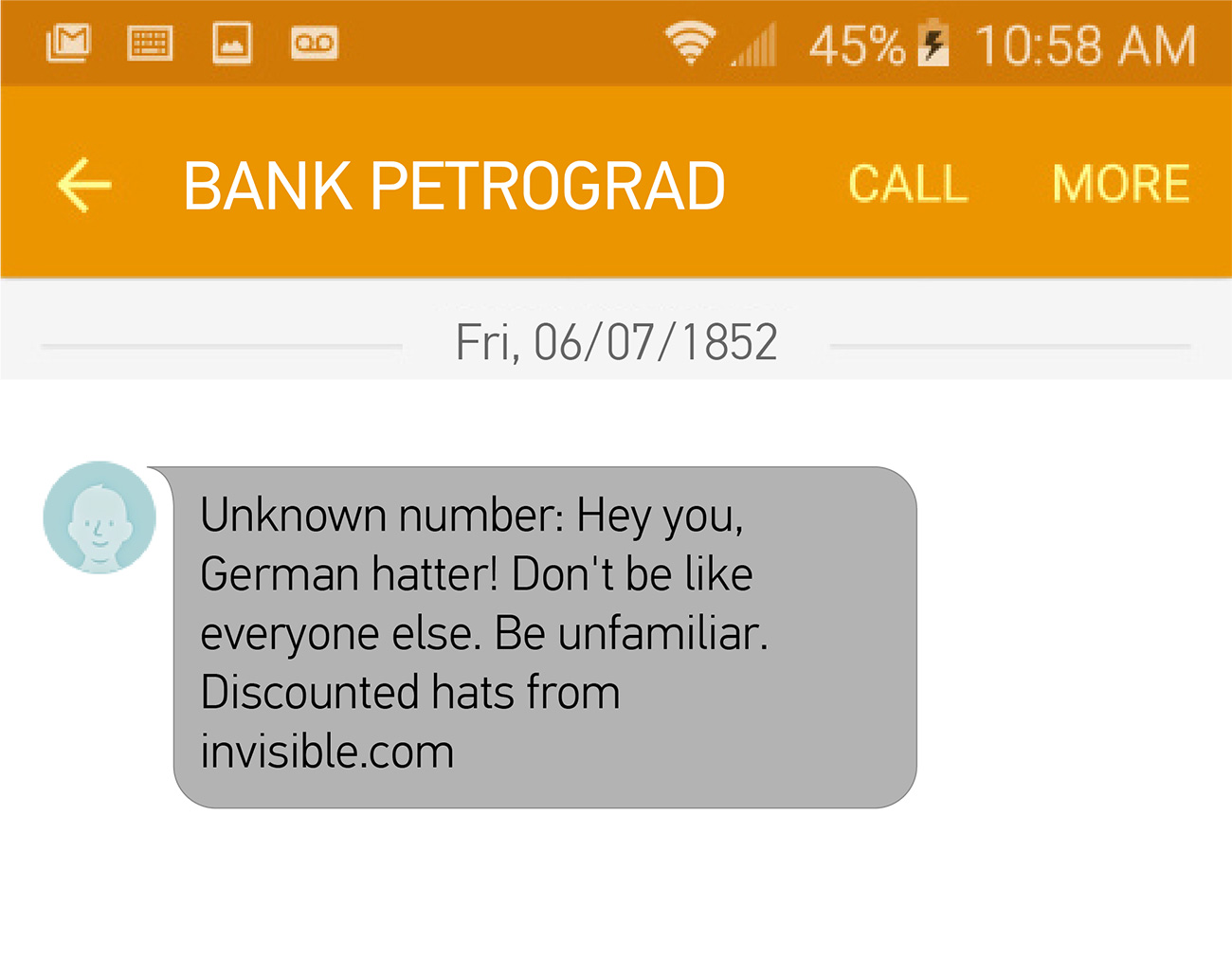

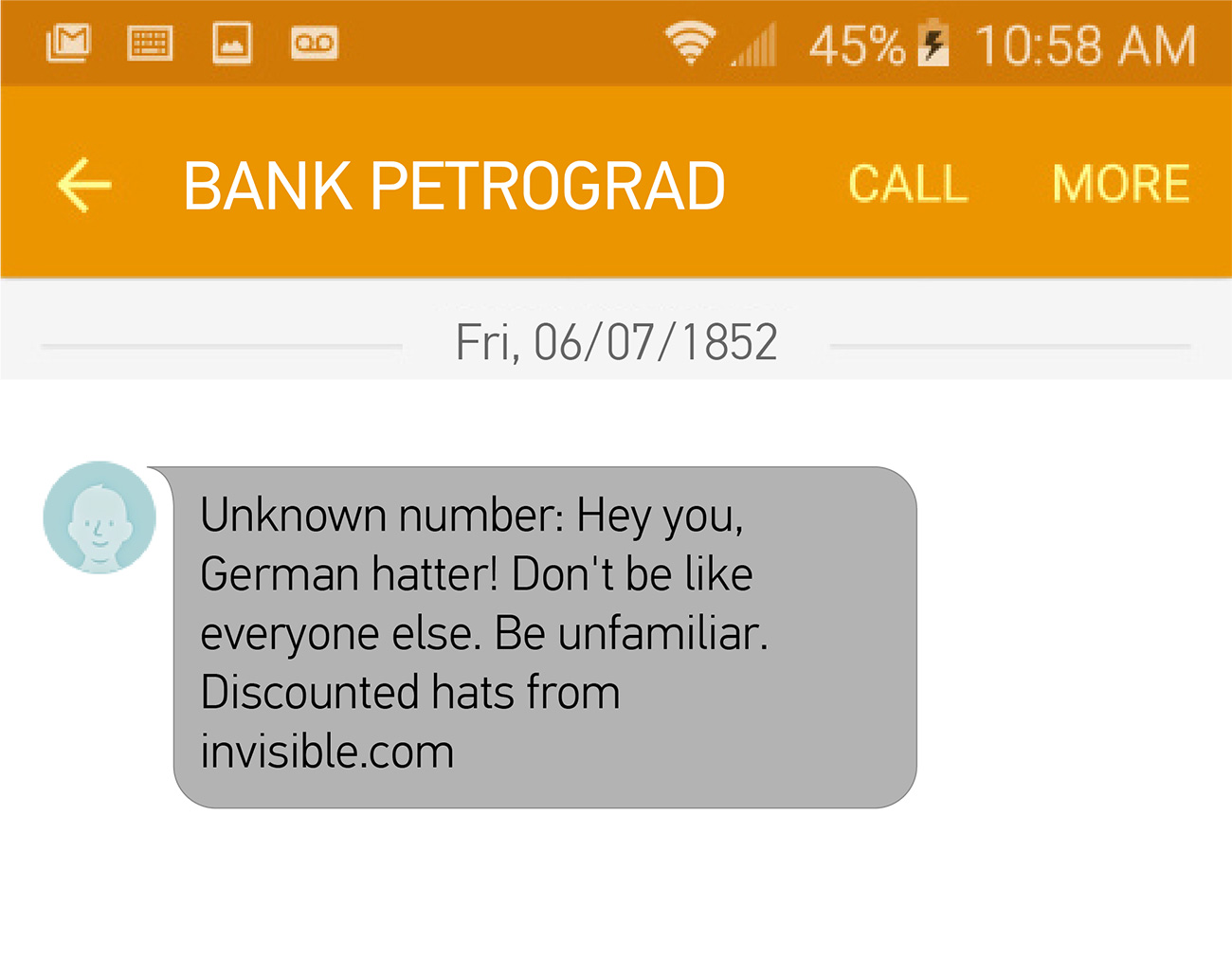

And yet when a drunken man who, for some unknown reason, was being taken somewhere in a huge wagon dragged by a heavy dray horse, suddenly shouted at him as he drove past: "Hey there, German hatter" bawling at the top of his voice and pointing at him—the young man stopped suddenly and clutched tremulously at his hat. It was a tall round hat from Zimmerman's, but completely worn out, rusty with age, all torn and bespattered, brimless and bent on one side in a most unseemly fashion. Not shame, however, but quite another feeling akin to terror had overtaken him.

Extract from the book:

He tried to pull it out from the front of the dress, but something held it and prevented its coming. In his impatience he raised the axe again to cut the string from above on the body, but did not dare, and with difficulty, smearing his hand and the axe in the blood, after two minutes' hurried effort, he cut the string and took it off without touching the body with the axe; he was not mistaken—it was a purse. On the string were two crosses, one of Cyprus wood and one of copper, and an image in silver filigree, and with them a small greasy chamois leather purse with a steel rim and ring. The purse was stuffed very full; Raskolnikov thrust it in his pocket without looking at it, flung the crosses on the old woman's body and rushed back into the bedroom, this time taking the axe with him.

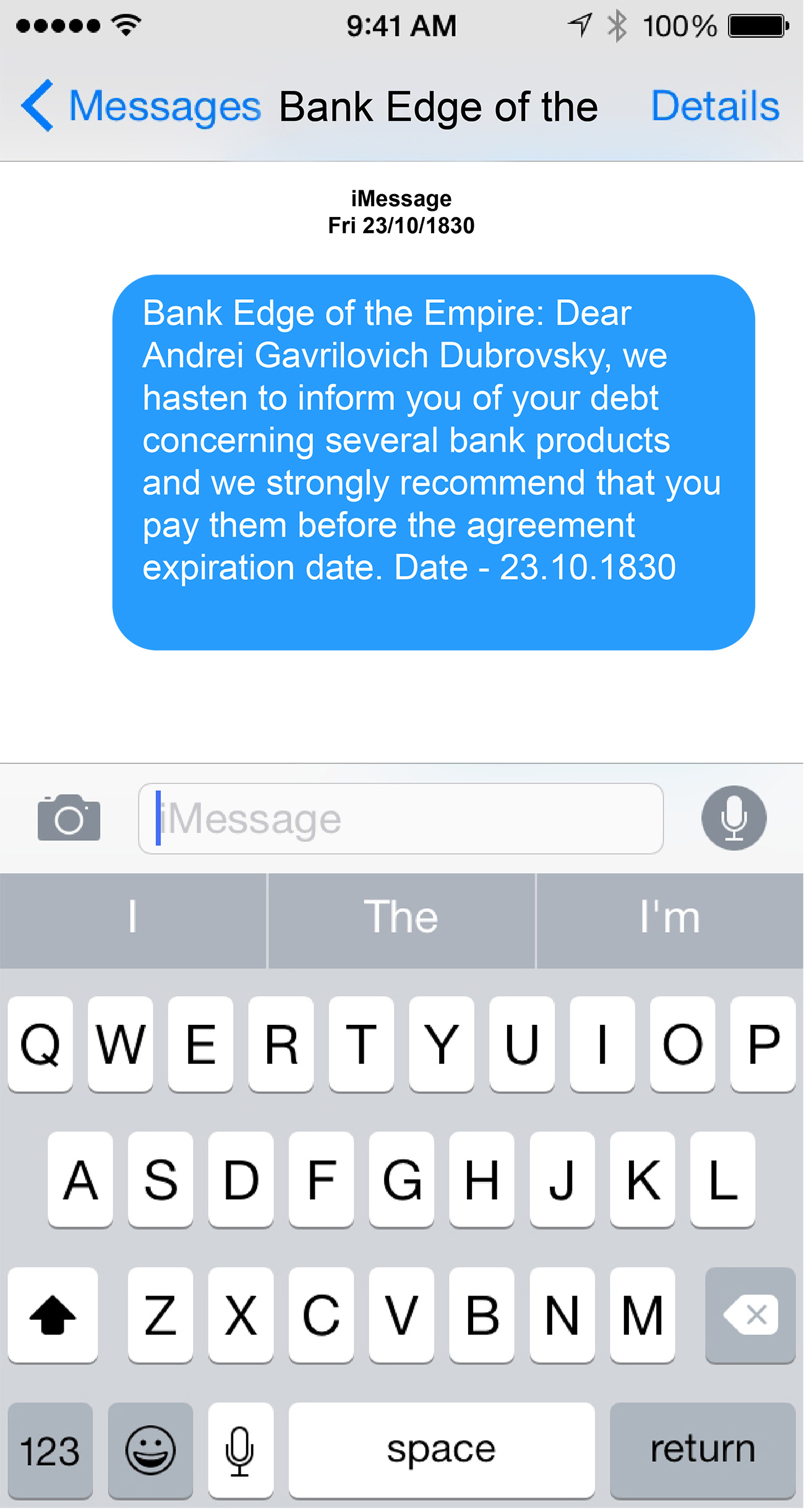

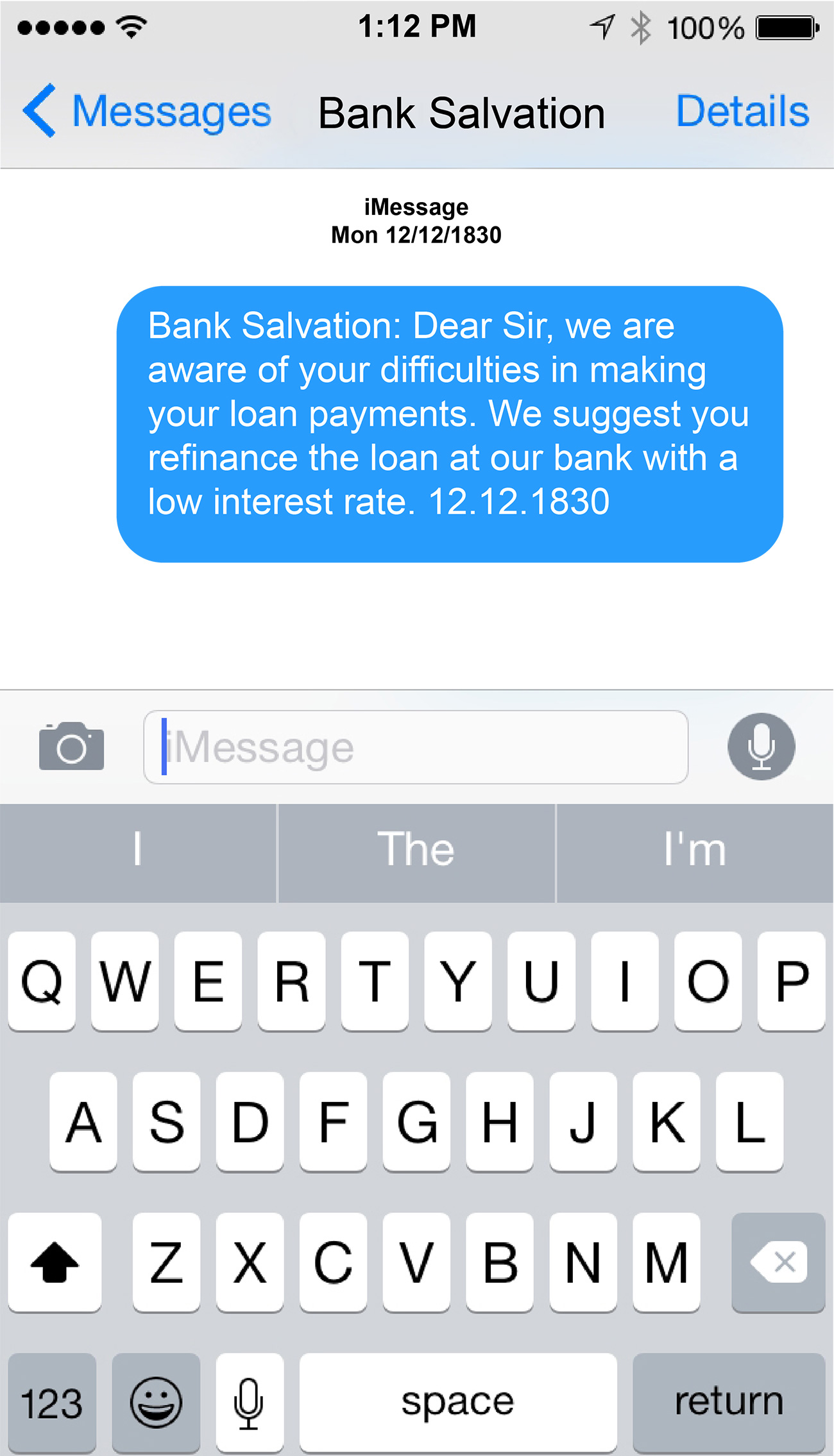

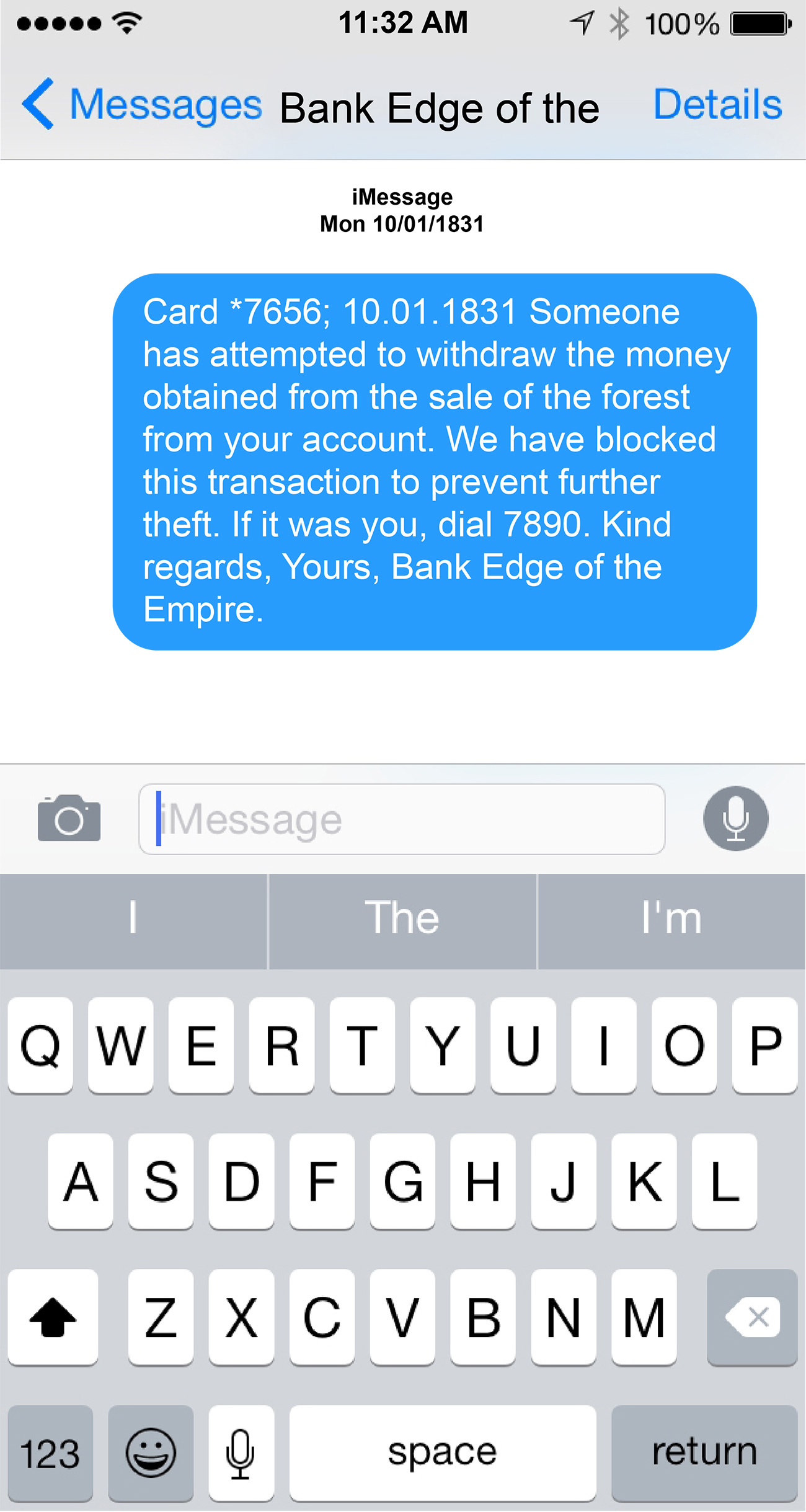

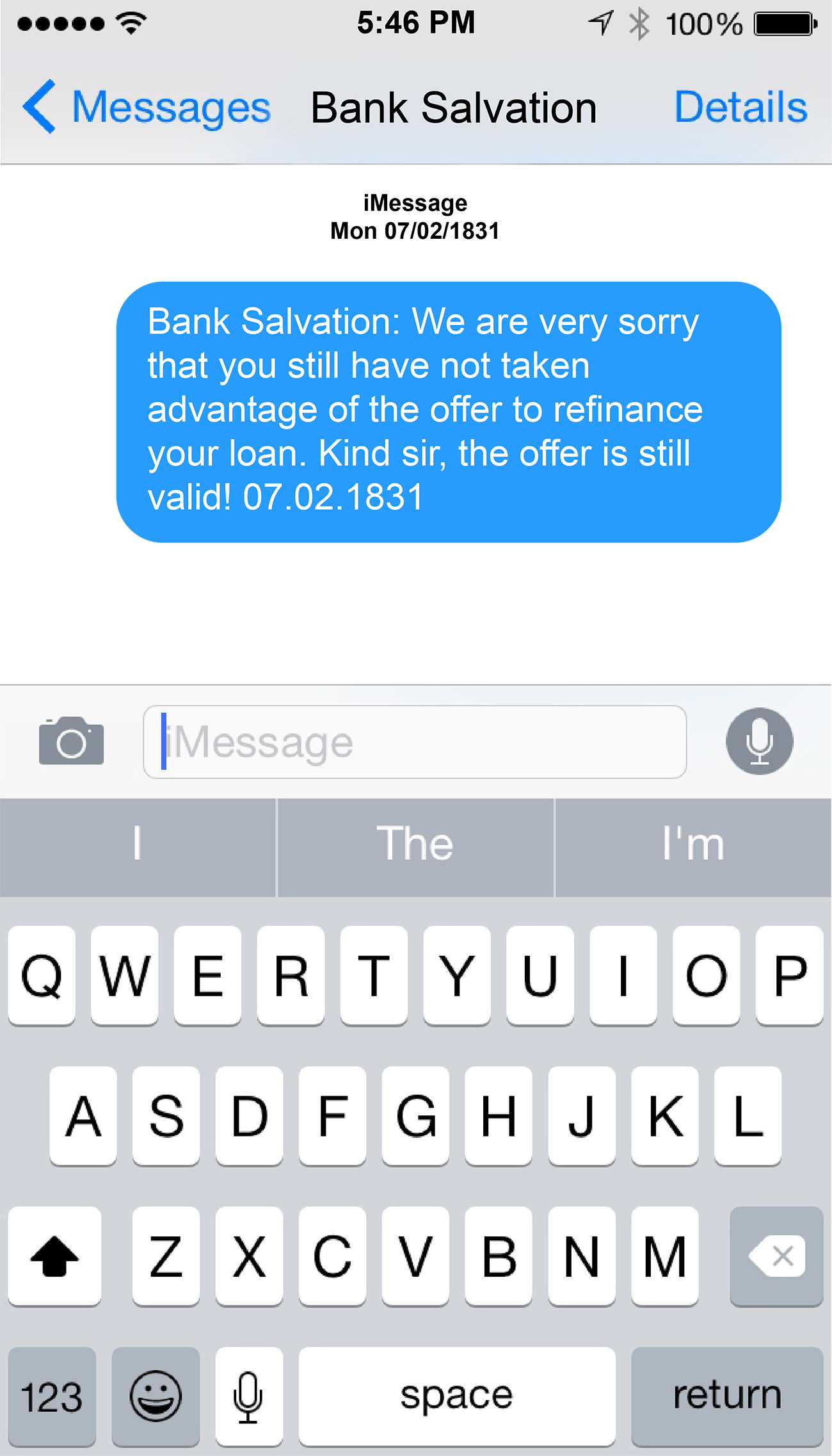

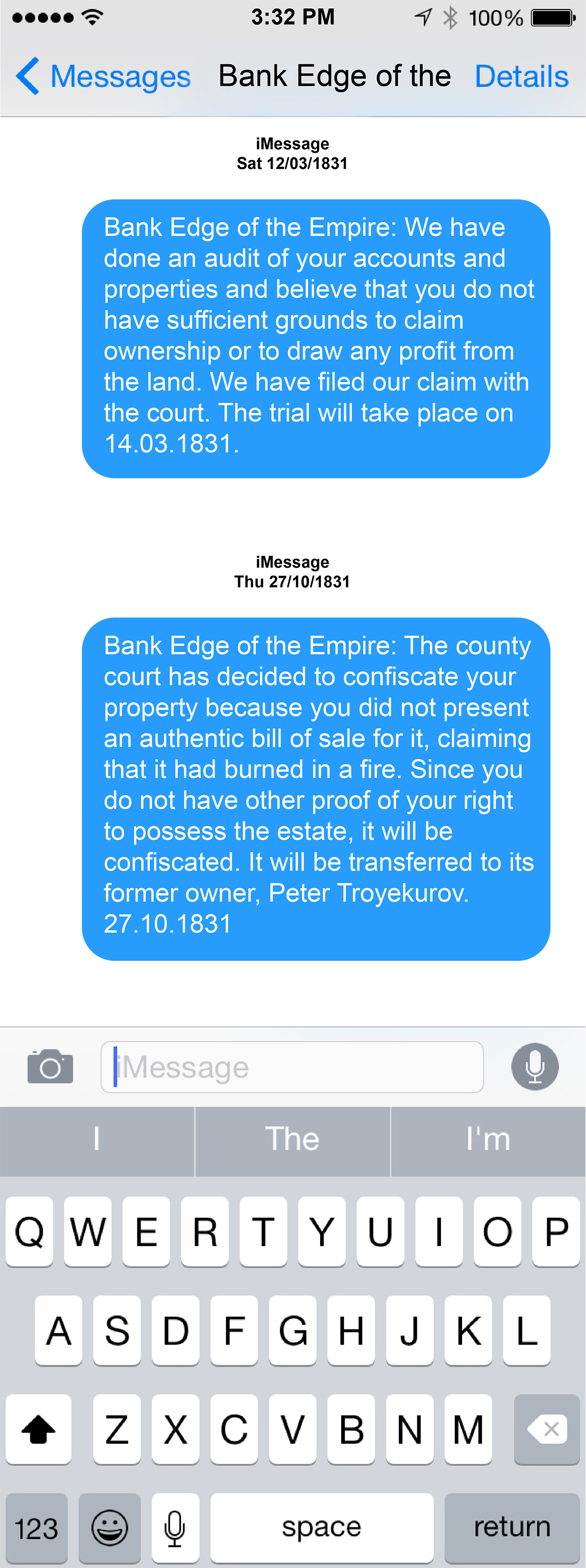

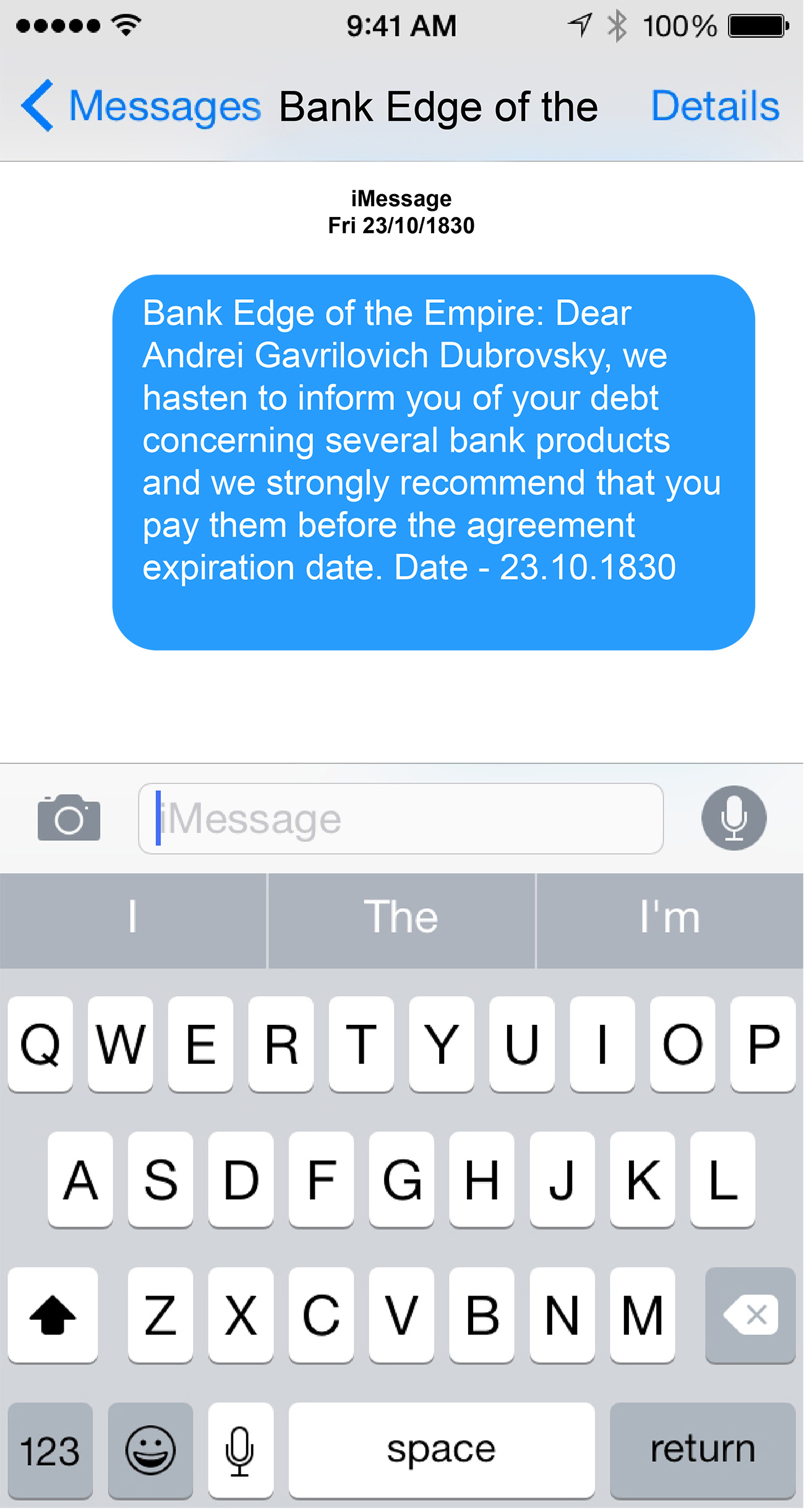

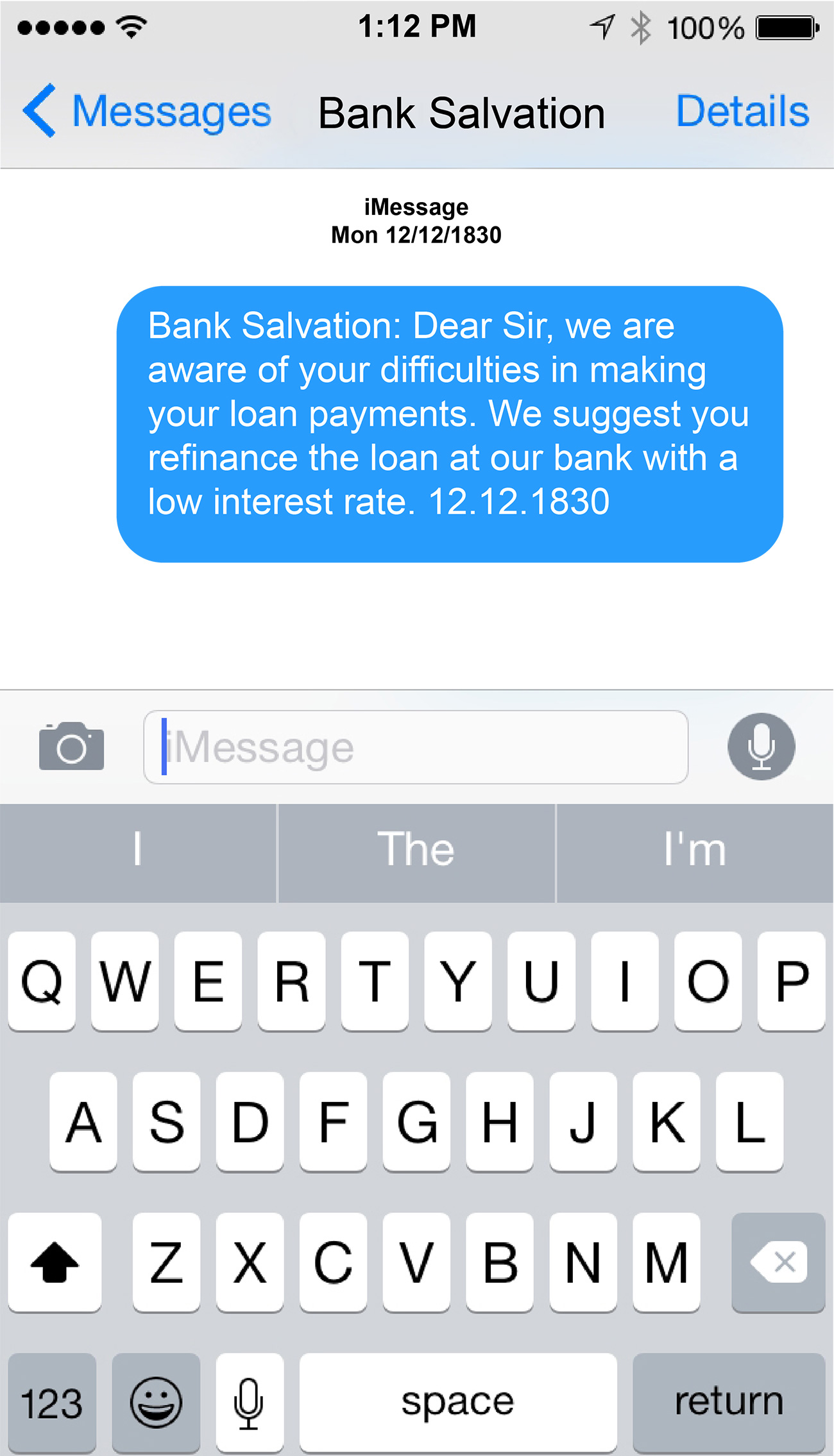

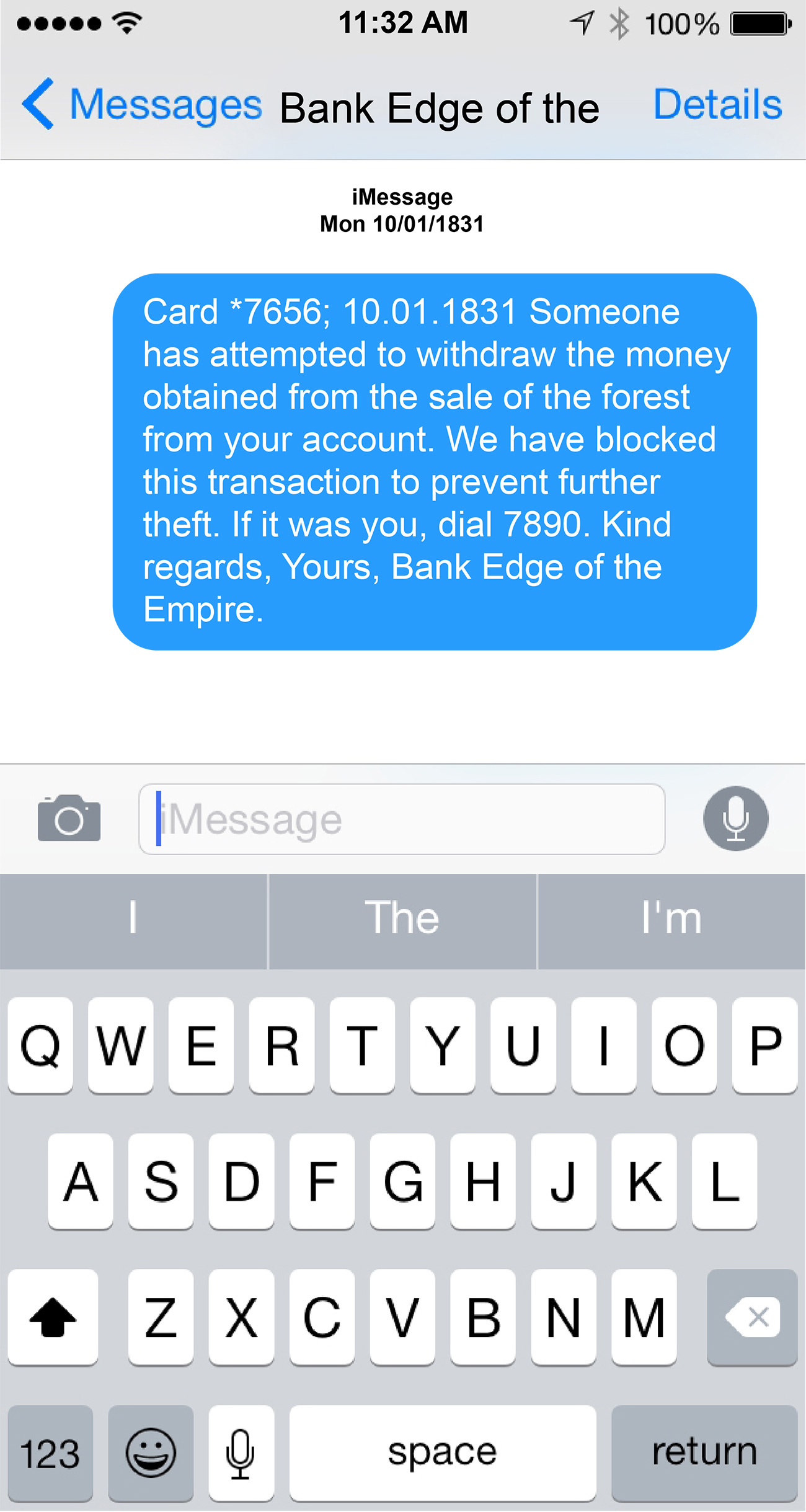

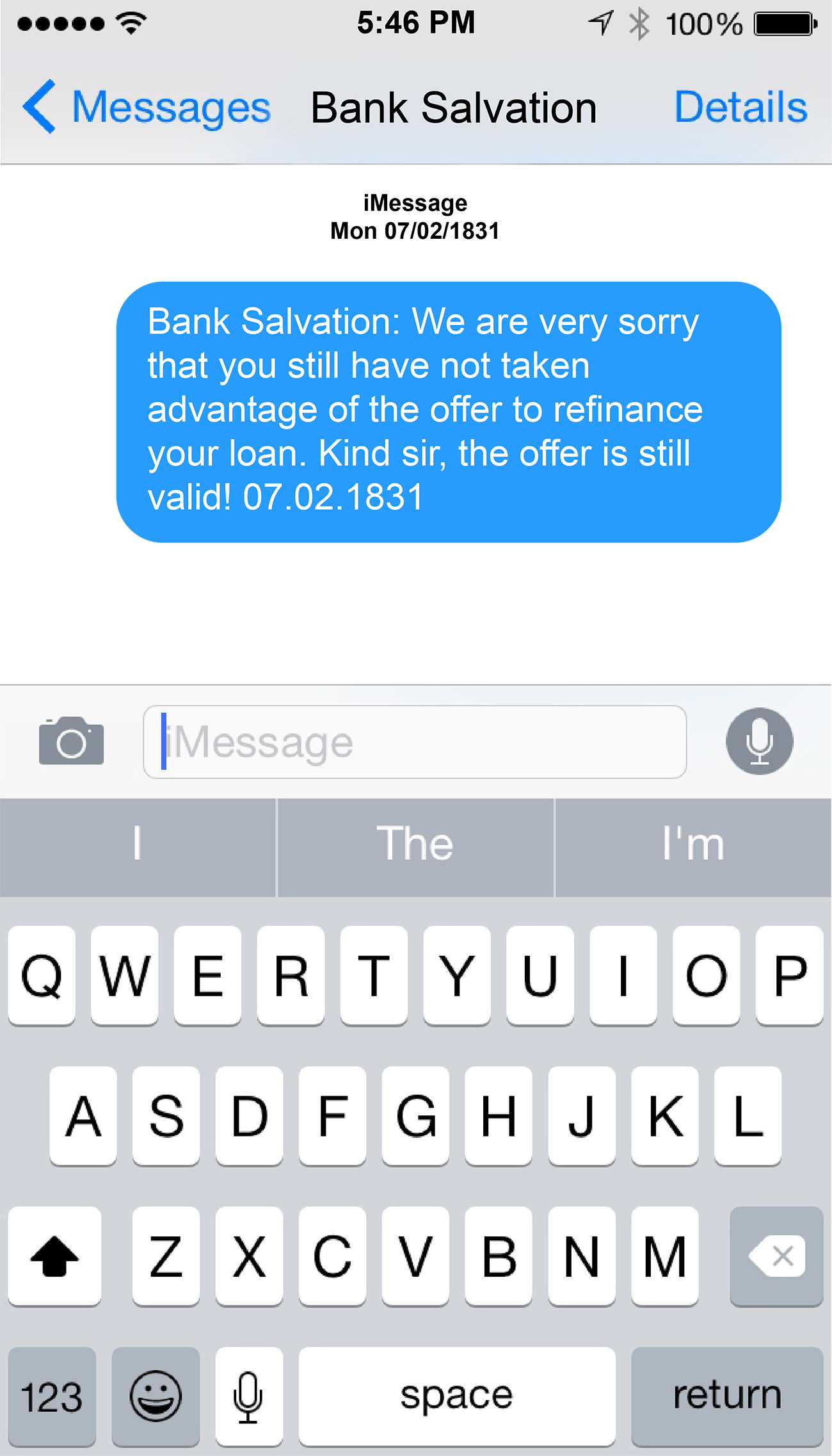

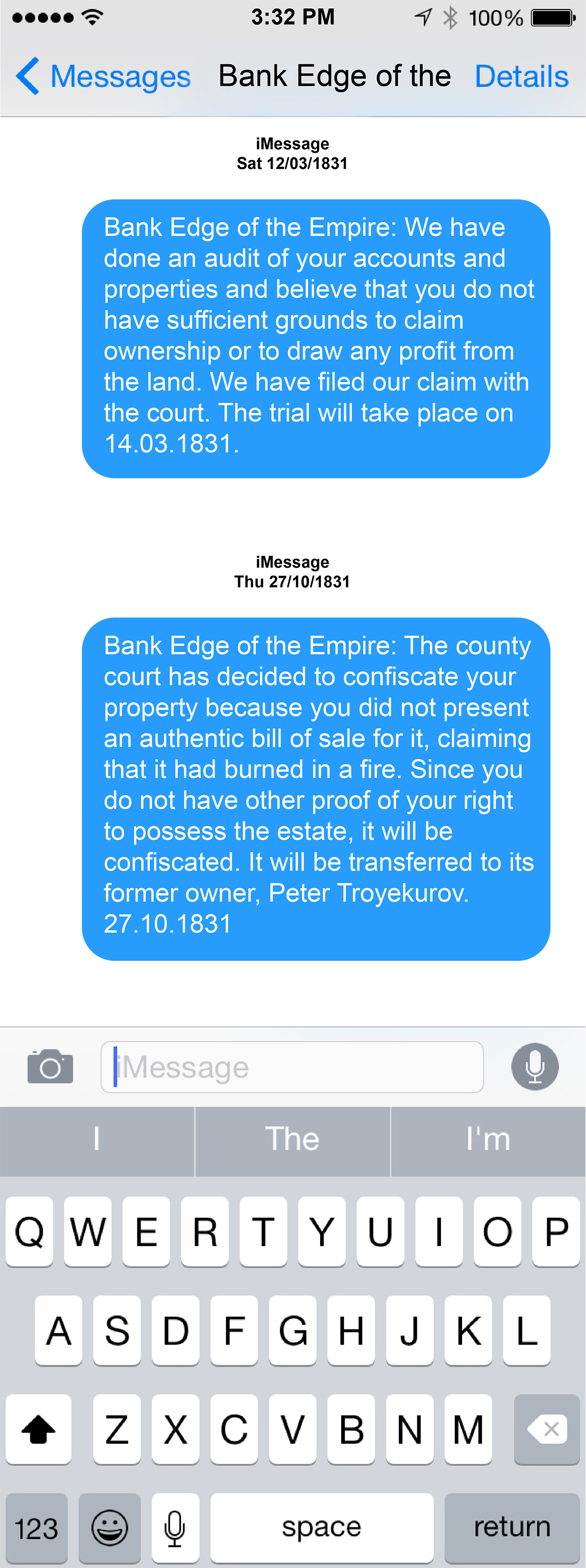

Dubrovsky by Alexander Pushkin: The case of the confiscated property

Vladimir Dubrovsky's father, a poor landowner, falls victim to his vindictive, proud and wealthy neighbor who could not forgive his reluctance to forgive rudeness. The essence of this conflict, which will bring the novel's protagonist into the family fold, is extremely simple. If the plot were to take place in today's reality, the text message story of these fights would look like this:

Extract from the book:

Dubrovsky, his affairs involved, was obliged to send in his papers and settle down in the village, which now constituted his entire property. When Kirill Petrovich heard of this, he offered him his protection, but Dubrovsky, while thanking him, preferred to remain poor and independent.

Extract from the book:

Dubrovsky was driving round his little domain. As he approached a certain birch copse his ears caught the sound of an axe ringing against wood, and the next minute there was the crash of a falling tree. He made his coachman drive quickly up to the copse and came upon some peasants from Pokrovskoye, calmly stealing his timber. On his appearance they fled helter-skelter. Dubrovsky and his coachman caught two of them and brought them, tightly bound, to the yard in front of the house. Three of the enemy’s horses were also 15 captured by the victor. Dubrovsky was exceedingly wrath. Never before had Troyekurov’s men, notorious scamps as they were, dared to play their tricks within the confines of his estates, for they knew of his friendly relations with their master.

Read more:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Illustration of Gogol's 'Dead Souls,' Chichikov (L) visits Plyushkin / Getty Images

Illustration of Gogol's 'Dead Souls,' Chichikov (L) visits Plyushkin / Getty Images