Alexandra Guzeva in the camp dorm. Source: Alexandra Guzeva

Alexandra Guzeva

My summer dreams have always been related to camp… For three years in a row, at the ages of 14, 15 and 16, I spent three weeks at the seaside (usually close to the Ukrainian city of Kherson) with my classmates. Honestly, the place we stayed looked very much like a real pioneer camp from Soviet times.

We had morning swimming. We formed a line and took off our shoes; our leader counted the pairs of shoes and blew on a whistle – that meant we could go swimming. When he blew again, we had to immediately get out of the water. Then the shoes were counted again to make sure the number of shoes matched the number of kids.

This may sound weird and even harsh, but for us it was really fun! No one ever argued.

Pre-disco look (3rd left). Source: Alexandra Guzeva

The older we became, the more camps were about discos (дискотека), checking out the boys and taking on creative tasks as a whole group. We also learned English, played volleyball, and prepared mini-performances (dancing or reading poems). And of course we made new friends!

Ridiculous story: Once, when we arrived at our first camp, the director told us that we should be good kids and behave ourselves, before adding: “By the way, here is the place for smoking, please do not smoke anywhere else but here.” This was long before the anti-smoking campaign!

Elena Bobrova

I went to the same camp in the Leningrad Region for four years from 1996-1999. It was called Raketa (Rocket). One of the main things that was typical for children’s camps in Russia then was that the camp leaders were keeping you busy all the time.

We were divided into groups (otryadi, отряды) based on our age and we constantly had competitions between the groups, like best song, best comedy sketch (KVN), best dance.

Elena Bobrova (center, in red). The photo was taken in 1998, two years after the triumph in the Miss Rocket competition. Source: Elena Bobrova

One thing that happened at camp really had an impact on my personality. In my first year, when I was just 11, I won the “Beauty and Talent girls competition” and became Miss Raketa.

My weakest part was singing, but then one of the girls who had a beautiful voice got sick, so in the end I came first. Since most of the kids went to the same camp every year, I was kind of famous for my victory for several years, which is very important when you are a teenager.

The best parts of camp, of course, were the discos and the farewell evening fire. At the discos, everyone waited for the slow dances (medlyaki, медляки) when the boys would ask girls to dance.

Morning roll-call, or “Lineika”, was obligatory every morning. All the children had to present themselves there and greet each other. Sometimes plans for the day were announced there by the camp director. Source: Elena Bobrova

Because of those times, I can’t listen to songs like Toni Braxton’s “Un-Break My Heart,” Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You” and the Scorpions’ “Wind Of Change” without a smile, because they were our the most popular tunes for medlyaki.

On the last evening we were allowed to stay up longer. We built a big fire and were just hanging out and singing songs with a guitar. The most popular was Pereval.

The next day, everyone was crying because when camp was over, it meant that summer was practically gone and the time of going back to boring school was coming.

Anna Sorokina

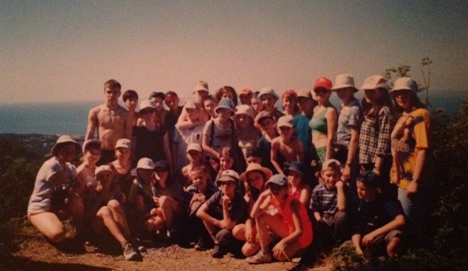

My summer dreams are tied to my school days. When I was a teenager, I usually spent all summer camping. From 1998-2002, every summer I visited many interesting places across Russia with my friends and classmates. We traveled around Lake Baikal with backpacks and tents, enjoyed the fountains of Peterhof, climbed in the Caucasus Mountains, had a turn in the resorts of the Krasnodar Territory (Sochi, Anapa, Adler, Tuapse).

Somewhere in the Caucasus Mountains, 2001 (2nd row, 2nd left, in the blue panama). Source: Anna Sorokina

My most memorable summer vacation was at Lake Seliger in 1999. That year, we spent one month at the lakeside, living in tents. Our group ranged in age from 7 to 15. We had no cell phones, no shops, no internet and no parents, just several teachers who were accompanying us.

We made a bathroom in the forest and the boys (who were no older than 15!) made for us a portable shower by putting a water tank on a tree. And the teachers lived the same way we did.

We all had to help make the camp work, and we took turns doing jobs in the kitchen or around the campfire. There were about 20 children in the camp and we each took three or four turns.

Two girls and two boys worked in the kitchen. The boys brought the food (sometimes they even fished for it) and made a fire, and the girls cooked something tasty and laid the table in the biggest tent.

At night, the person on duty guarded the camp from aliens and kept the campfire going, since it got cold at night. Although the person on night duty didn’t sleep, no one refused to do it. We knew that the best way not to fall asleep was to set a roll of toilet paper on fire and unroll it as it burned.

We paddled across the lake in kayaks, fished, swam - and had beautiful evenings around the bonfire. We sang songs to the guitar, danced and organized events like the Day of Neptune, when you had to throw every person you met that day in the water (we called it “giving someone a bath”).

At the 'normal' camp in Adler (near Sochi), 2002. Source: Anna Sorokina

Of course, in Russia today most camps are 'normal' - children live in comfortable dorms, eat normal food and call their parents every day. But sometimes I miss those times when parents could leave their children for a month without feeling anxious.

Lara McCoy

My very first job was with a small team that produced a magazine about Russia in English. There were only about 10 of us on the project, and every summer our receptionist would invite us and our families for a cookout in the woods near her house.

We took the commuter train about half an hour to a town in the Moscow Region. Then we hiked through the woods to a clearing accessible only by crossing a stream by means of walking across a large pipe (I once did this while carrying a stroller).

The female members of the team would start cutting up vegetables to snack on while the guys set up the grill and started cooking the meat skewers - known as shashlyk - that our receptionist and her mother had marinated all night.

While the food was cooking, we played games. I say “we,” but really I mostly watched as my co-workers took turns reciting Pushkin or acting out scenes from Chekhov. I do speak Russian, but what I realized watching them was that the shared knowledge and experience required for these games went far deeper than simply the ability to speak the same language. I only began to understand how this shared culture develops when my children, who attend Russian schools, were required to memorize poems by the great Russian writers from the very beginning of first grade.

Not to be left out of all the fun, we did also play a version of Pictionary and I got pretty good at a came called “I’m going to the North.” (Ya poyedu na sever, Я поеду на север). And of course I wasn’t left out of the eating.

Many expats say that the mark of really being accepted by Russian friends or colleagues is getting an invitation to a dacha. I think that pales in comparison to hanging out in the woods looking for hedgehogs while reciting lines from Ruslan and Lyudmila.

Alastair Gill

As a long-time resident of St. Petersburg, for me summer in Russia has always been characterized by the ethereal atmosphere of the white nights of June and July, when the city seems to fall into a heady dream in which the most fanciful encounters and events can occur, and the weightless nights turn the city into a strange phantom of its everyday self.

There is a sense that in these summer months the senses become more heightened, that the city and its population is about to detach itself from the anchors of daily life and float away – a far cry from the dark days of winter when everyone seems weighed down by heaviness and the city can feel suffocating.

There is a certain hour at around 4 o’clock in the morning on midsummer days, when the great avenues and boulevards are deserted and shafts of sunlight are already painting the facades and embankments, in which, walking home from a friend’s house or some party, you experience the city as if it were an empty stage set for you alone, and the borders between reality and dream become blurred.

The uneven sidewalks and flagstones and the summer thunderstorms which always seem to sweep over the city at this time of year also mean that the streets often serve as large broken mirrors that magnify the sense of space and provide curious new perspectives.

Singing classes? Figure skating lessons? Join the club!

Russian schoolchildren no longer fit into their uniforms

Murzilka, the yellow fluffy protagonist of the children's magazine

In fact, many of my most indelible memories of summer in Russia are associated with thunderstorms. The weather will build until the city or countryside are sweating in a sultry warmth, and then black thunderheads will slide in and suddenly drench the land in an almost tropical downpour, leaving drains overflowing and squares awash. Perhaps it is not surprising that these moments make an impression.

So besides the unreality of June mornings in Petersburg, summer for me will always be the buildings of a Soviet suburb flickering in lightning and the sharp scent of ozone from a fifth-floor window, or feeling water sluice down my back as I run for shelter on a leafy Yaroslavl street, or marveling from the deck of a passenger ship on a great Siberian river as the wilderness is lit up by electric storms, or boiling water for coffee with a girlfriend in a sodden pine forest, or a hesitant goodbye in the rain.

Click to enlarge the infographics. Drawing by NataliaMikhaylenko

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox