What came before luxury hotels, yachts, villas, and the Forbes rating?

V.Tarabashchuk/TASSSome of them never dreamt of millions, others only had money on their mind.

Whatever the case, Russians who became millionare oligarchs almost overnight generally weren’t peddling oil and diamonds, far from it. They were pioneers.

Artyom Tarasov, the first officially declared millionaire in the Soviet Union, passed away on July 23 at 67. The businessman said that he never imagined amassing such a fortune and was instead focused on science, but everything changed when the Mikhail Gorbachev era presented new opportunities. Tarasov said he would have been a fool not to have taken advantage of the situation, and like Tarasov, the following characters struck while the iron was hot - but in unexpected ways.

It all began in the late 1980s, when ordinary Soviet citizens first received the right to have a bank account. But how did one make money?

Artyom Tarasov had the bright idea of launching a marriage bureau: “Back in those days, if you were not officially registered as living in accommodation in Moscow you had no chance of finding a job,” he recalled. “And the only way to get registered in the city was to marry a local. This is why we received 4,000 potential customers in the first five days of operation. Each paid 25 rubles ($43 at the time). We raised 100,000 rubles ($172,414) for the 12 of us, when the average wage in the country was still 130 rubles ($224) per month.”

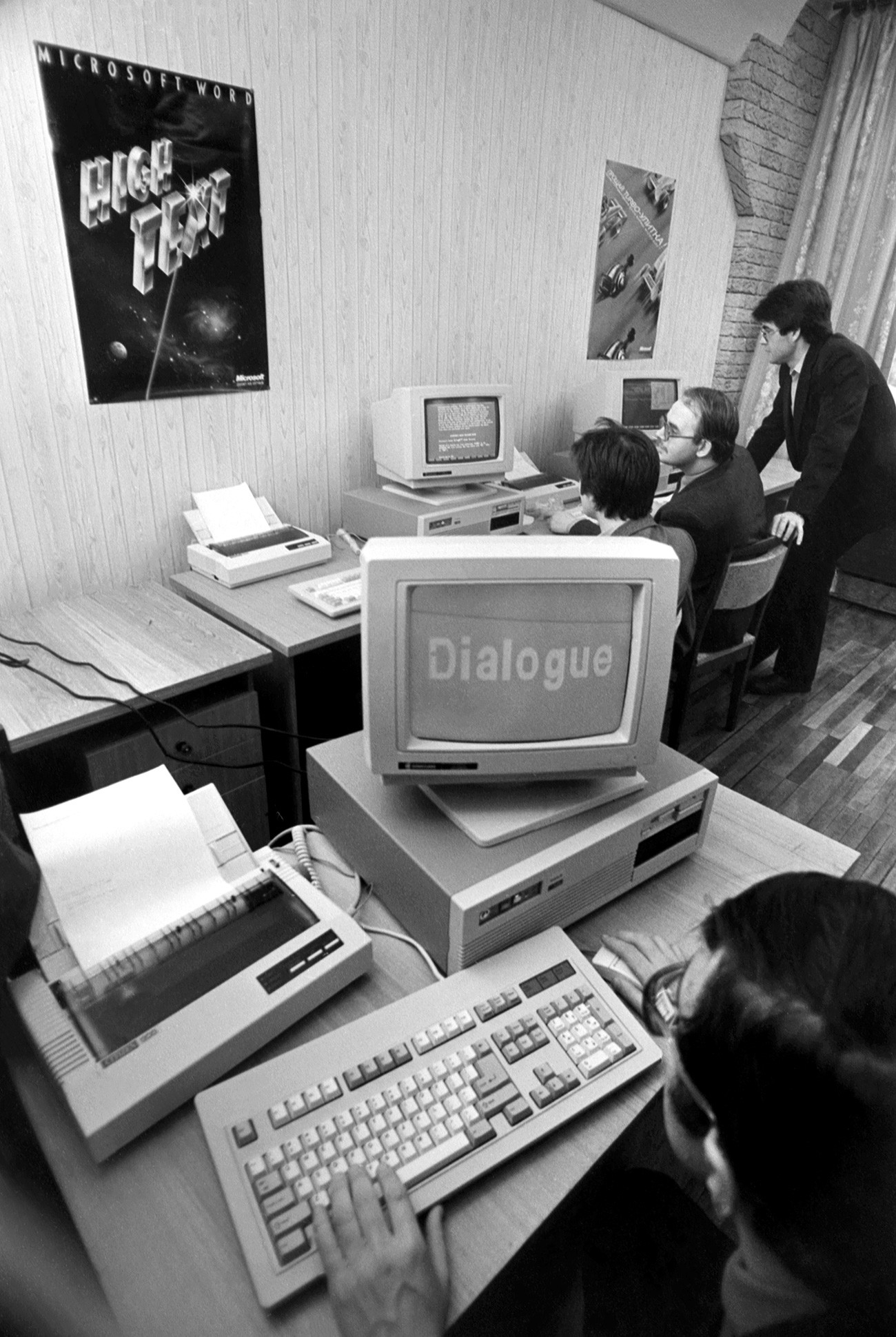

This particular business only lasted six days though. The authorities decided that a marriage bureau was too immoral an enterprise for the Soviet Union. So Tarasov put his thinking hat on and set up a repair shop for imported household appliances. There were virtually no such enterprises in the USSR due to the lack of original component imports. This is how the Tekhnika (Equipment) company arrived on the scene. The idea was to localize foreign software sales before peddling on to the government.

“What do you know? In the first month of operation we earned one million rubles [$1.7 million],” Tarasov said. “Honestly, we were all shocked to get that first million: We had the suspicion that all of us would soon be executed for this.”

There was already rudimentary software in the country but no hardware. “We started by buying dollars in cash from luxury prostitutes at three rubles per dollar.” An acquaintance traveling abroad would take the money, buy PCs with it and bring the equipment to Russia. “A computer would cost us 1,500 rubles [$2,586], and we would then sell it to a state-owned enterprise for 50,000 rubles [$86,206].” Now that’s a healthy markup.

German Sterligov

TASSBefore he started selling luxury coffins and what some believe to be Russia's most expensive bakery products at 1,650 rubles ($28) per loaf, Orthodox Christian entrepreneur German Sterligov made his first serious money organizing concerts in the waiting rooms of Moscow's railroad stations.

The artists, normally buskers picked from the streets, would perform for 15 minutes, collect the money, and move to another station, before being replaced by a different band. “We carried cash in suitcases, and it only took each of us a couple of months to buy a car,” Sterligov said. “The main problem was to exchange the small coins for bills. Nobody asked us to pay for hiring the premises back then, we didn’t even pay the cops for protection, which made them very sad. That was in 1988.”

Later that year these impromptu concerts were banned, and Sterligov switched to another activity. While watching an American movie, he got his first glimpse of the stock exchange, and was so inspired that soon after he rented a hall, installed large screens and computers, and set up Russia’s very own exchange, Alisa - easy as pie! The first day of operation generated no more than six million rubles ($10.3 million) for the owner.

The 1991 coup only helped the business: “I was at our New York branch at the time; the cost of Russia's debts immediately dropped to nearly zero. On the same day we bought up a lot of debts and sold them three days later. I had predicted that the coup would be thwarted within three days, and this is what happened. We made huge profits.”

Roman Abramovich

SputnikWhile still a school senior, Roman Abramovich bought and sold cigarettes, chocolate, jeans, and perfume at a significant profit. He decided against going to university because who needs a degree when you can sell?

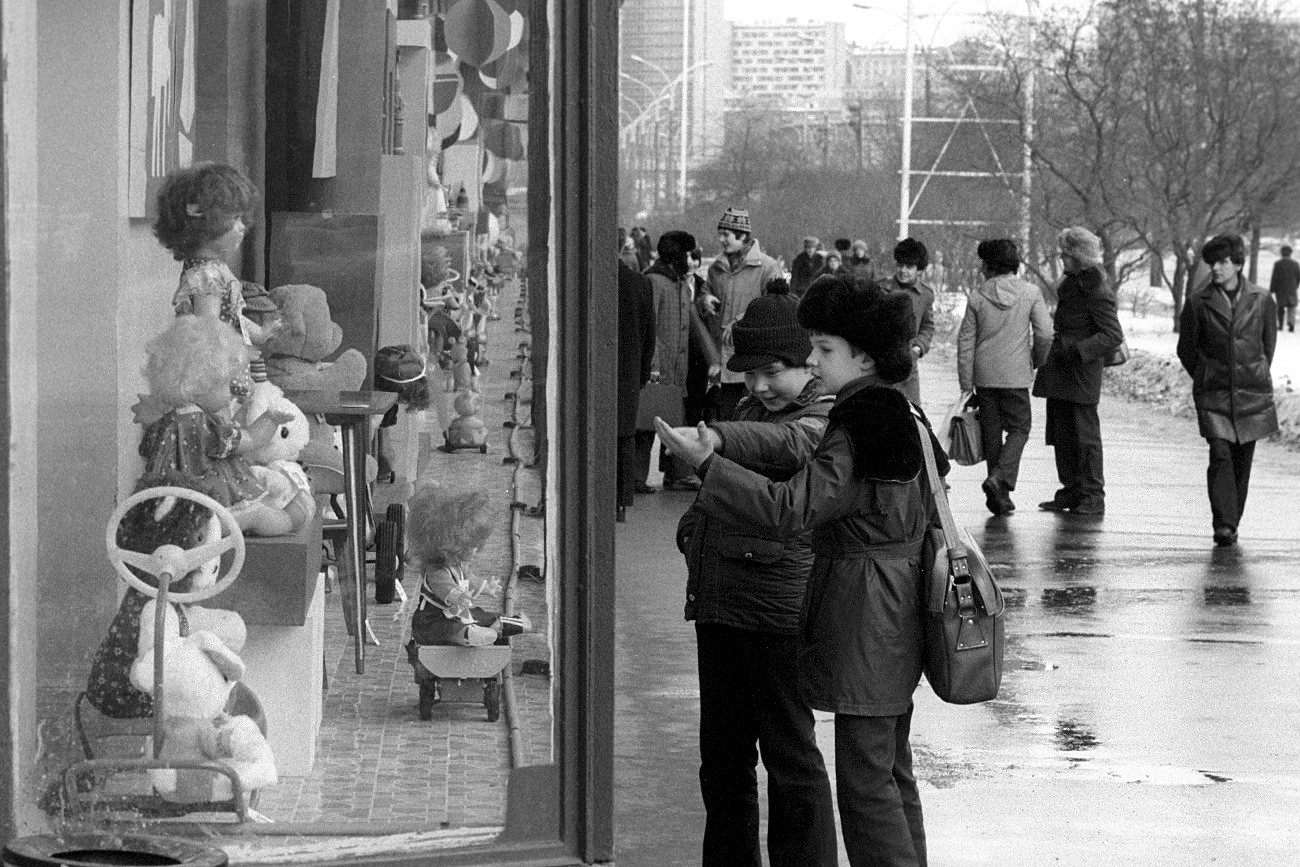

At 22, Abramovich established Uyut (Comfort), a company selling selling toys made of polymeric materials. A friend of his was involved in a similar business activity. Abramovich - who already had a wife and daughter at this point - started manufacturing the dolls in their apartment.

First they started selling the toys in hotels, then at underground stations, and finally, in department stores. Eventually, Uyut products could be found across Russia. While the average monthly wage in the country stood at 100 to 200 rubles ($172 to $344), Abramovich was raking in between 3,000 to 4,000 rubles ($2,142 to $2,850) per month. Several years later, however, he pulled out from the market and switched to hydrocarbons. “Toys were never the end goal for me,” says the owner of Chelsea F.C. who is worth $9.1 billion (as of 2017, according to Forbes). “They were an available route toward my goal, which was to set up a business that could develop.”

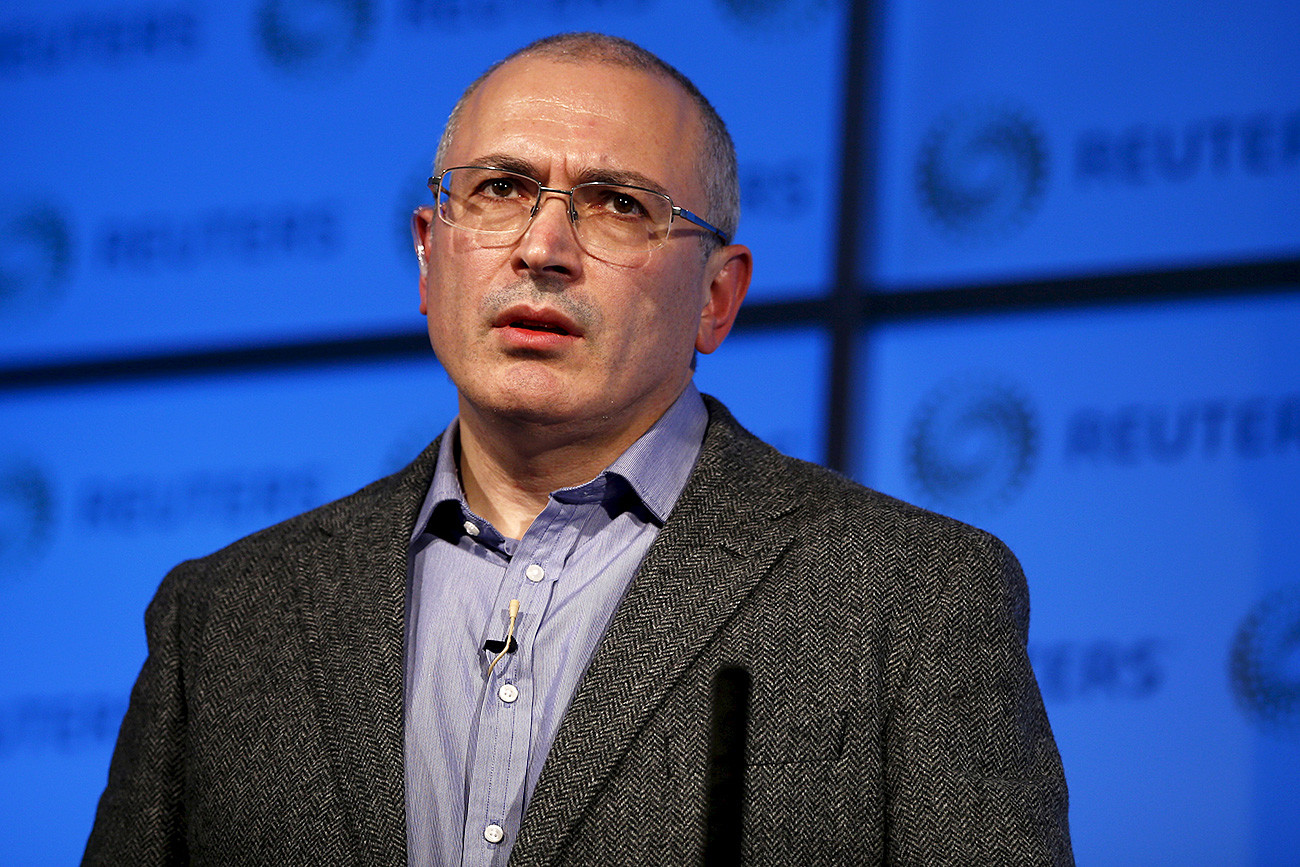

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Khodorkovsky and his business partners set up a so-called center for scientific and technical creativity of the youth (abbreviated to NTTM in Russian), another type of commercial enterprise allowed back in those days. There were only 33 NTTMs across the Soviet Union in 1987. Like all companies, they had the ability to convert virtually worthless rubles bank accounts into cash.

“In fact, the law on state-owned enterprises gave such an opportunity to anyone interested, but you had to do things rather than sitting on your hands,” Khodorkovsky later recalled.

His NTTM became one of the first in the USSR to start offering money cashing services at a huge commission. Production factories, scientific centers, and design bureaus all rushed to use Khodorkovsky's company because the government contract system was beset by red tape.

The enterprise earned around 80 million rubles ($137 million) in 1988 alone, and soon afterward established its own cooperative bank.

The official ruble exchange rate stood at 58 kopecks per dollar in 1988

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox