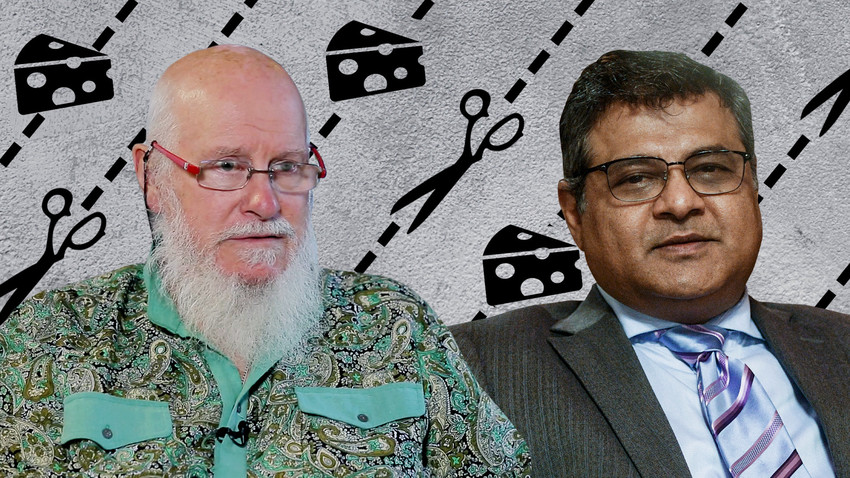

Sammy Kotwani came to Moscow from India in 1990 with $300 in his pocket and no knowledge of the Russian language. Nevertheless, he managed to set up a successful business, The Imperial Tailoring Co., and now clothes Russia’s political and cultural elite. He has since entered the international market, making suits for the leaders of the former Soviet republics.

When the virus first broke out in China, Kotwani’s entrepreneurial instinct told him that it would be serious: “I do business in China and have an office in Hong Kong. We knew about the coronavirus as early as January.” He brought his children back from their studies in England, and made his home his main office and workshop.

His tailoring shop has not been taking orders for the past two months, focusing instead on adapting to the new work conditions, and only inside Russia at that. Kotwani has introduced a new service for clients: suit maintenance. He claims to be the only one in the world to offer it. Once every six months, Kotwani cleans and irons them, sews on new zippers or linings, and readjusts them to the owner’s size in case of weight loss or gain (very relevant after quarantine). The service is absolutely free, although covered by the initial high cost of the suit.

Everything is now done and made at home. But where do the fabrics come from? Before the lockdown, Kotwani had more than 100,000 in store, including some very expensive ones. Surprisingly, the pandemic didn't affect his stock. International air freight continued, so he still orders fabrics from England and Italy through DHL and UPS.

During the pandemic, the Russian government offered all business owners an interest-free loan of 12,000 rubles (about $170) per employee, which Kotwani took advantage of. In addition, the landlord of the commercial premises where his studio is located agreed to reduce the rent by 50% during the downtime.

After 30 years of work, Sammy has no intention of quitting Russia. “My business will flourish thanks to the quarantine,” he says optimistically about the future. “People are already tired of wearing masks. How much longer will it go on for? When the lockdown ends, I think everything will be fine.”

Mr. Kopiski asks to be called in the Russian manner — by first name and patronymic, that is, John Ianovich. He looks more like Ded Moroz (Russian Santa Claus) than a stiff-upper-lip Englishman; likewise his values are closer to the Russian soul — family and spiritual wealth as opposed to the material kind.

Twenty-five years ago, John bought a former collective farm in the city of Petushki, Vladimir Region (made famous in the bookMoscow-Petushki by writer and satirist Venedikt Yerofeyev). A few years ago, he decided to try his hand at agritourism, a completely new business for Russia. He set up a dairy farm with a cheese-making plant, plus a hotel with 20-30 rooms and a restaurant. At first, local residents believed it to be the country retreat of some oligarch.

The hotel and restaurant had to be closed during the lockdown, but that didn’t reduce the amount of work to be done at the dairy farm. At the start of the pandemic, John had 4,000 cows that he affectionately (if not very politely) calls “women”. In his view, cows need protecting from stress, just like people, and the better their living conditions, the higher the quality of milk they produce.

“Food sales fell by 30% because several stores in Moscow closed, especially in the large shopping malls.” Online sales went up slightly, but mainly in Moscow, and delivering there from Vladimir Region is uneconomical.

John admits that he has own personal perspective on the virus: “Every year we have the flu. This year is just a little worse than usual. Sure, we listened to the advice of the government and the president, but we believe it’s more about politics than the pandemic.”

A religious man, John puts his faith in God and believes that the situation with coronavirus in Russia isn’t all that bad, though it’s a tough lesson all the same. And despite his view that “capitalism is now bankrupt,” his family will never want for the essentials: milk, bread and meat.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox