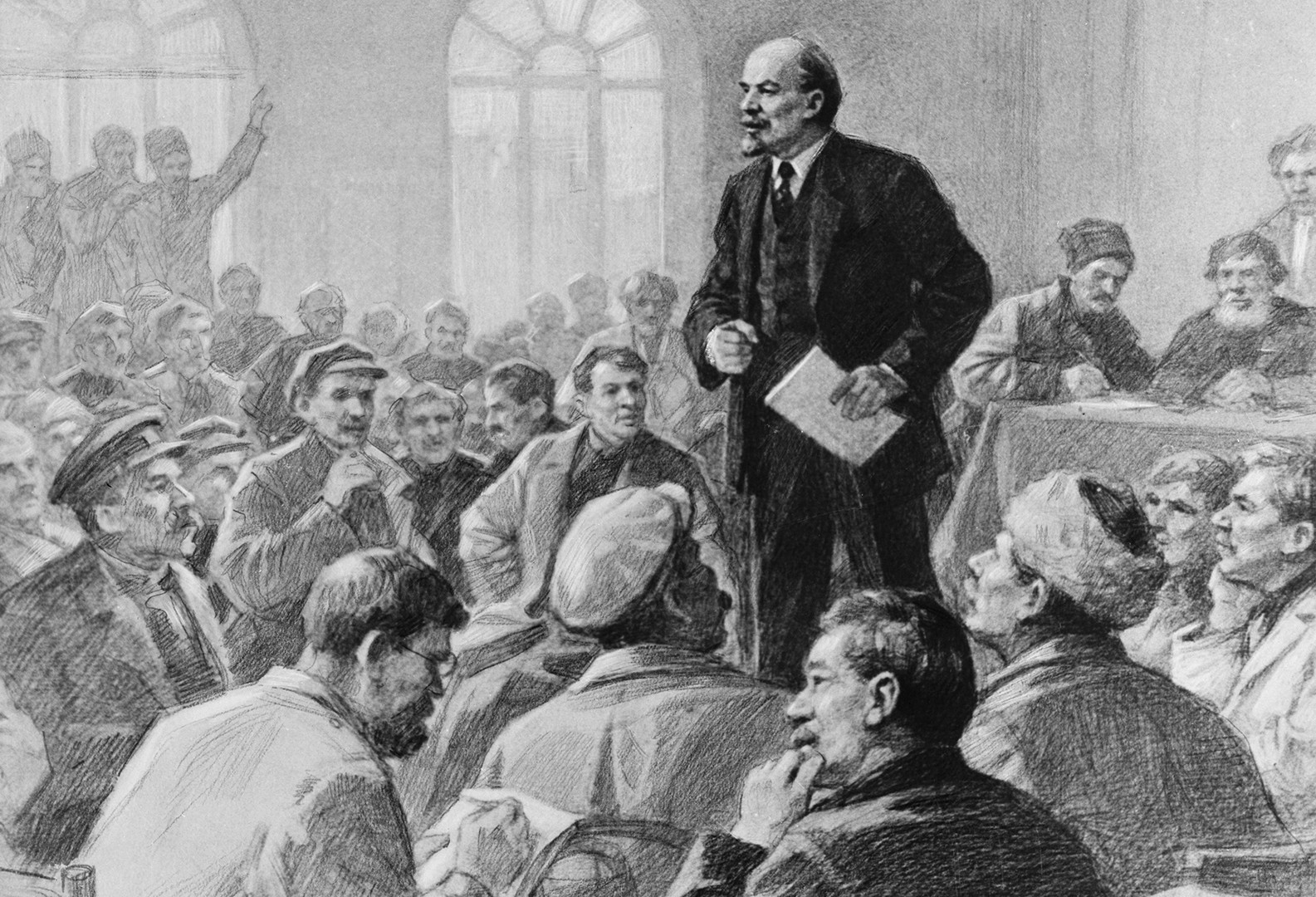

Vladimir Lenin gives a speech at a meeting.

TASS/TASSImagine you’re a Bolshevik revolutionary in late 19th/ early 20th century Russian Empire. Your goal is to smash this "prison of nations," to crush capitalism, to give land to the peasants, and factories to the workers. Your party is banned, however, and your leaders are abroad. The tsarist police are hunting you and your comrades, and you might be arrested at any moment. On top of that - you need money. Lots of it.

You need money for everything: printing newspapers, forging documents, making bombs, as well as buying weapons for shootouts with police and a possible uprising. Walking into a bank and asking for a loan "to bring down tyranny" is most likely not an option, especially if your manifesto calls for nationalizing banks and creating a moneyless society (as the Bolsheviks did). So what can you do?

Revolutionaries in the Russian Empire didn’t like the word "robbery," preferring the term "expropriation" (or simply "ex"), but that didn’t change the essence of what they did. Heavily armed men attacked banks and stole money, killing those who put up resistance. In a 1906 article, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin – in justification of such of violence - compared the situation to a civil war, where anything goes.

The Bolsheviks carried out their biggest "ex" in June 1907 in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia). Several militants threw bombs, and opened fire, at a bank coach that was carrying 250,000 rubles (over $5 million at the current exchange rate). Five guards were killed, and the Bolsheviks fled with the money.

Private donations made up a considerable chunk of Bolshevik "earnings," says historian Yevgeni Spitsyn. On one hand, many workers who sympathized with the cause shared their meager incomes with the revolutionaries, providing a modest but stable source of income. On the other hand, the revolution also had much wealthier sponsors.

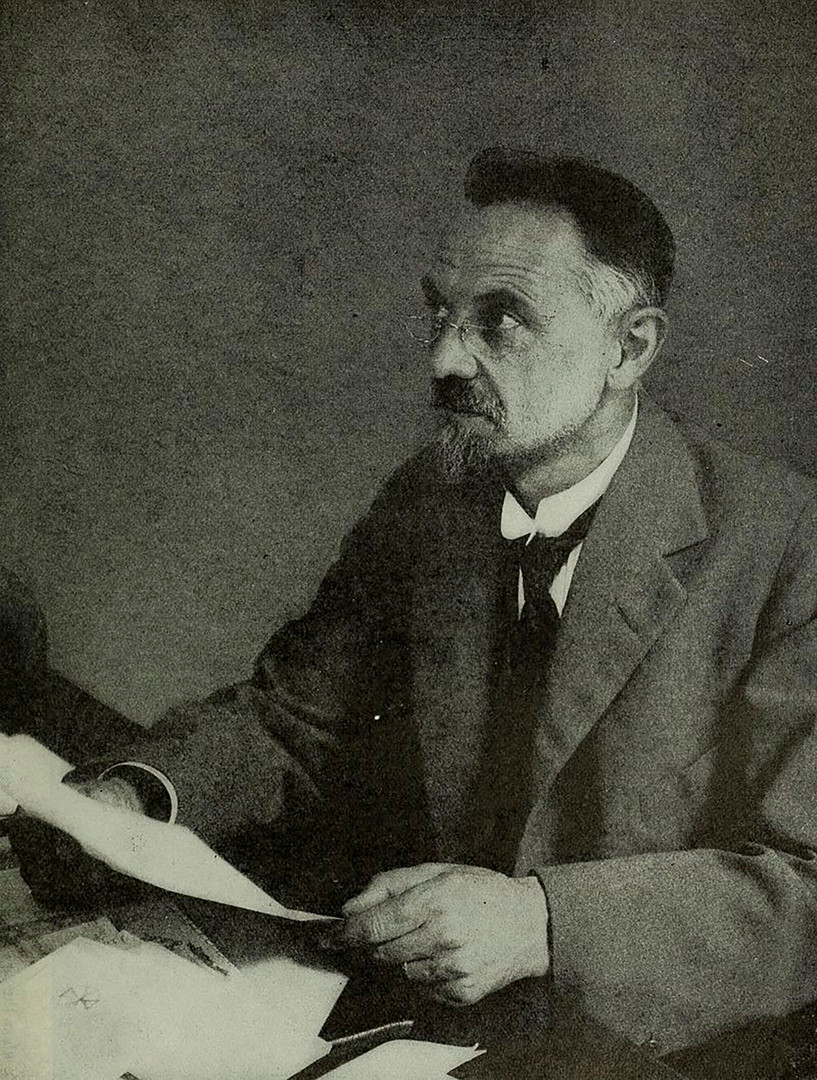

Leonid Krasin, a Bolshevik leader responsible for finances, wrote in his memoirs about the years from 1900 up until 1917. "[Among well-off people] it was considered a sign of good taste to donate money to revolutionary parties."

Some prominent people, such as writer Maxim Gorky, donated money out of sincere sympathy, but others such as wealthy factory owner Savva Morozov did it because they weren’t sure who’d emerge victorious: the tsarist government or the Revolution. Basically, they hedged their bets by supporting both sides.

Portrait of Leonid Krasin.

Wikipedia.orgKrasin was highly resourceful and cunning, able to convince rich sympathizers to part with their money for the sake of the revolution. Once in Baku (now Azerbaijan) he showed up in the dressing room of legendary theatrical actress Vera Komissarzhevskaya, who was known for her opposition views, and demanded that she give a "charity" concert as soon as possible, and donate all the proceeds to the Bolsheviks.

Komissarzhevskaya was so taken aback by his audacity that she agreed, and in the end she collected several thousand rubles for Krasin. With that money, the Bolsheviks opened an underground printing press in Baku.

Krasin was the mastermind behind another major Bolshevik swindle. This time, in order to replenish the party's coffers the revolutionaries married off two young women after the arrest and death in prison of their brother, Nikolay Schmidt, a wealthy factory owner who sympathized with the Bolshevik cause.

Nikolay Schmit on his deathbed.

Wikipedia.orgAccording to Schmidt’s last will and testament, his fortune went to his sisters, Yelizaveta and Yekaterina, who wanted to donate the money to the Bolsheviks. The sisters, however, had an uncle who exercised control of the money, and he was not prepared to trust the young women with it no matter what (he was unaware of their fondness for revolution).

The Bolsheviks had to find husbands from among the party ranks for the sisters so that the uncle would provide them with a dowry. After the ‘weddings’ with their Bolshevik husbands in 1908, the money was handed over to the party.

Accusations that the Bolsheviks, including their leader Vladimir Lenin, were spies hired by Germany to destroy Russia in World War I, were first made as early as 1917 when Lenin and his inner circle were allowed to pass through German territory on their way from Switzerland to Russia. Bolshevik opponents even among the revolutionaries accused them of taking money from the Germans.

Most contemporary historians believe, however, that reality was far more complex. Germany indeed let Lenin into Russia hoping that the radicals would end the war, (which they did). And money for financing the Bolsheviks most likely was allocated. For example, the British historian Jonathan Smele writes that by the end of 1917, the German General Staff had invested over 30 million marks into Russian opposition parties, (not just the Bolsheviks).

Still, there is no evidence of direct links between the Bolshevik leadership and the Germans. Oleg Budnitsky, a professor at the School of History at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, points out that, "the Bolsheviks were very clever people and excellent conspirators."

Furthermore, says Andrei Sorokin, head of the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI), the very fact of receiving funding from the Germans does not mean that the Bolsheviks were German agents. Most likely, they took the money without any strings attached, trying to use Germany for their purposes, just as Germany tried to use them for its own ends.

Read more:

A bloody end: 4 Russian tsars brutally murdered before 1917

Why was Nazi Field Marshal Paulus on the Soviet payroll

Revolutionary women: 3 iron-willed females who changed Russia forever

Virgin Lands Campaign: How the USSR tried to counter food shortages

'Dog-headed people': What was Ivan the Terrible's ‘oprichnina’ force

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox