Gorky Street (now Tverskaya) in Soviet era.

Fedor Kislov/TASS

Yuri Dolgorukiy, known as a "founder" of Moscow, depicted by historian V. Vereshchagin.

Prince Yuri Dolgorukiy of Suzdal invited Prince Svyatoslav to the city of Moscow. “Come to me, brother, to Moscow,” wrote Yuri, according to the ancient Hypatian Chronicle. When he did, Yuri threw a great feast, proving that even medieval Moscow was a wonderful place to party in.

White Kremlin of Moscow (before being rebuilt).

Eduard Gaertner / Charlottenburg PalaceAs Moscow’s power grew, its look changed. The Kremlin fortress in the heart of the city was initially wooden, but then Dmitry Donskoi (ruler in 1359 – 1389) rebuilt its walls with limestone, and thus, the city was given the epithet, belokamennaya, (white-stoned).

Limestone seemed fragile to Ivan III, so he rebuilt the Kremlin in 1485-1495 using Italian architects, who made red brick walls, giving it the look you see today.

Ivan the Terrible.

S. Rostvorovsky (1858-1888) / Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine ArtsAfter decades of political struggle, wars and intrigues, Moscow became the absolute dominant political force in Russia. Ivan the Terrible assumed a new title, crowning himself “tsar”(literally “caesar,” meaning emperor). Moscow now ruled the country with an iron fist, and proclaimed itself “the Third Rome” - the last hope of Orthodox Christian civilization.

Red Square in Moscow with St. Basil's Cathedral in the center of it.

Fyodor Alekseyev / Tretyakov GalleryWhile not the biggest church in Moscow, St. Basil’s Cathedral (its official name is Pokrovsky Cathedral) is probably the most iconic one, dominating Red Square and incarnating the eclectic spirit of the city. The building actually is comprised of nine small chapels, each dedicated to its own saint. Ivan the Terrible ordered the cathedral built after he conquered the Khanate of Kazan, expanding Russia’s territories eastwards.

Kuzma Minin calls Russians to arms in order to free Moscow from the Poles.

Mikhail Peskov / Samara Art Museum

During the harsh years of the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century, Moscow was captured by the Polish army, which had been invited to Russia by one of the factions competing for the throne. Until 1612, when the militia led by Kuzma Minin and Dmitri Pozharsky liberated the city, Muscovites had to live under foreign occupation. Soon after victory, a new era started: Mikhail Romanov became Tsar in 1613.

Senate Square in St. Petersburg, the new capital of Russia.

K. Ludwig / Hermitage MuseumMoscow lost the status of capital when Peter I, admiring his newly built St. Petersburg, made it the new capital. This did not mean, however, that nothing important happened in the old capital. Russian emperors were still crowned here.

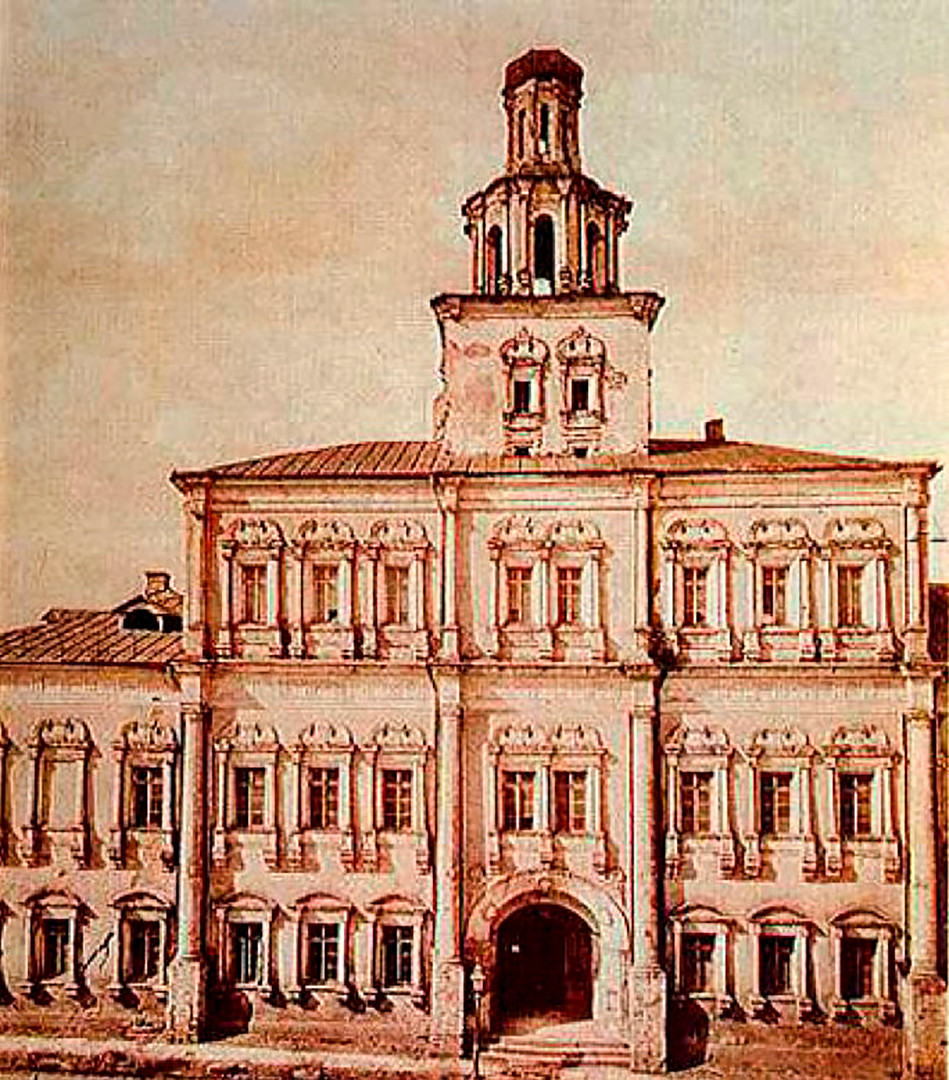

The first building of Moscow University.

Dmitry SmirnovIn 1755, the first classic university in the history of Russia was founded in Moscow. The greatest Russian scientist of that era, Mikhail Lomonosov, was the driving force behind it. Even today Moscow State University remains No. 1 in the country.

Napoleon's army after his military defeat in Russia.

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier / Public domainNapoleon Bonaparte’s army invaded Russia in 1812, and after months of battle the French emperor managed to capture Moscow. This was not much of a victory, however, because the city had been abandoned, and soon after the occupation a great fire started.

Muscovites set their city on fire because they were eager to kick out the French any way possible. And they did: Napoleon soon left Moscow and was forced to retreat.

Gorky Street (now Tverskaya) in Soviet era.

Fedor Kislov/TASSIn 1918, the Bolsheviks returned Moscow its status as capital, this time of the new socialist state. Moscow had to change, however, and the Bolsheviks spared no effort modernizing the city to accord with their new state ideology.

Many churches, including the famous Church of Christ the Savior, were demolished. Also, Soviet authorities altered the city’s urban plan, demolishing ancient streets and widening main arteries, including Tverskaya Street and Novy Arbat. They also launched new transportation systems, and in the 1920s-1930s buses, trolleybuses and the metro appeared in Moscow.

November 7, 1941. Soviet troops parade past the Kremlin and march on to the front line.

Samary Gurary/TASSThis battle lasted from October 1941 to January 1942, and was the first Nazi defeat in the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945). While Wehrmacht troops had already advanced deep into Soviet territory, they met iron resistance outside of Moscow.

This was undoubtedly a heroic page in Moscow’s history. During the celebration of the October Revolution (Nov. 7) in 1941, the German army was just several kilometers away, but Moscow still held a parade. The soldiers went marching from Red Square directly to the battlefield where they stopped the ruthless enemy. The Soviet capital remained unconquered.

Olympic mascot Misha (bear) flies into the sky during the closing ceremony of the Moscow Olympics.

Semyon Maisterman, Nikolai Naumenkov/TASSThe biggest sports event in Moscow’s history, the 1980 Summer Olympics took place against a backdrop of international geopolitical turmoil. After the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, about 50 countries boycotted the Moscow Olympics.

Nevertheless, the Moscow Olympic Games was a success and the Olympic Mishka became one of the most recognizable sport mascots, and many people cried during his farewell during the closing ceremony. Many famous sports facilities, including the Olympiysky complex, the biggest indoor arena in Russia, were built on the occasion of the Moscow Olympics.

Russian soldiers in a tank near the Russian parliament building in Moscow on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 1993.

APThe political unrest of the early 1990s didn't leave Moscow unscathed. In 1991, the city was the stage for a hardline communist coup against Soviet reform leader Mikhail Gorbachev. The coup fell apart, however, after the army joined the protestors.

In 1993, Moscow saw more violence. Conflict between President Boris Yeltsin and Parliament led to deadly clashes, killing at least 120 people (the exact number is still not known). The military supported Yeltsin and blasted the White House from tanks – for the first and hopefully last time in Russian history.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox