Bones of tortured convicts of the Butugychag concentration camps in Kolyma

Nikolai Nikitin/TASSIn one of the most popular Soviet comedies, The Diamond Arm (1969), one of the main characters is a crook and fraud, and one day he shares a meal with a man from Kolyma. When bidding farewell, the man says warmly, “We’d be happy to have you in Kolyma!” But the crook, played by Andrei Mironov, nervously chokes and answers, “No, please visit us instead.”

Little surprise that Mironov’s character, who is afraid of justice, prefers to avoid Kolyma. This region in Russia’s Far East was for decades associated with harsh prison camps from which few returned. Unfortunately, it was not only criminals that were sent there. In the 1930s, when Stalin’s repressions where at their worse, many innocent people were sent to Kolyma, and they suffered unbearable hardships and death in the labor camps.

Gold-mining. Kolyma.

Global Look PressKolyma is an unofficial region of Russia, and gets its name from the Kolyma River and mountain range. Its territory covers two official regions – the Magadan Region and the Chuktoka Autonomous Region.

Remote even by Russia’s standards (the region's capital Magadan is situated 6,000 km east of Moscow), Kolyma up to the end of the 19th century was populated only by small indigenous nations such as the Chukchi and Evens.

This changed when scientists and travelers suspected that this region might have vast deposits of mineral wealth. During the Russian Civil War, one specialist, Eduard Anert, assessed Kolyma’s gold deposits at 3,800 tons. This assumption was bold at the time, but Anert’s research was eventually proved correct - Kolyma was extremely rich in gold.

After Soviet geologist Yuri Bilibin’s expedition to Kolyma in 1928 he claimed that its subsoil contained more gold than the remaining territory of the entire Soviet Union. When the turbulence of the Revolution and the Civil War ended, the Soviet state was able to mine the gold in the Far East. But to reach that gold under the surface, Kolyma would need a labor force, and that’s how the Gulag camps appeared.

Officially, it was not GULAG (Chief Administration of Corrective Labor Camps) that ruled the Kolyma labor camps. In order to make gold mining in the Far East as efficient as possible, Joseph Stalin in 1931 created a new and separate structure called Dalstroy(Far North Construction Trust).

This was a state-controlled trust subordinate directly to the Communist Party’s Central Committee, which was in charge of the entire Kolyma. Dalstroy’smission was to mine gold, tin, wolfram and at the same time build cities and villages, and develop infrastructure in the remote region.

A lot of prisoners of the Butugychag camp in Kolyma used to die producing tin and uranium manually without any protective gear at a former local uranium enrichment plant.

Pavlov/RIA NovostiFrom the very beginning the authorities used prison labor because it was hard to convince citizens to go voluntarily to the extremely cold Kolyma where there was no infrastructure or humane working conditions. The first group of prisoners arrived in November 1932, and not a single one of the 11,000 survived the winter, with guards and dogs also dying. Only by 1934 had Dalstroy established the basic conditions for humans to survive there.

The first group of prisoners arrived in November 1932, and not a single one of the 11,000 survived the winter, with guards and dogs also dying. Only by 1934 had Dalstroy established the basic conditions for humans to survive there.

The authorities finally got what they wanted: gold mining in Kolyma grew annually, peaking in 1940, with 80 tons produced annually. This was possible primarily thanks to the growing number of Dalstroy’s prisoners. In 1940, more than 190 000 convicts toiled “to gain back the trust of society” through exhausting labor. Both genuine criminals and political prisoners worked and lived together in Kolyma, and the fate of the latter was even harder.

“The camp never gave anything to anyone - and never could. Everyone, both prisoners and civilians, are corrupted by the camp,” wrote Varlam Shalamov, a Soviet writer who spent 14 years in Kolyma’s camps.

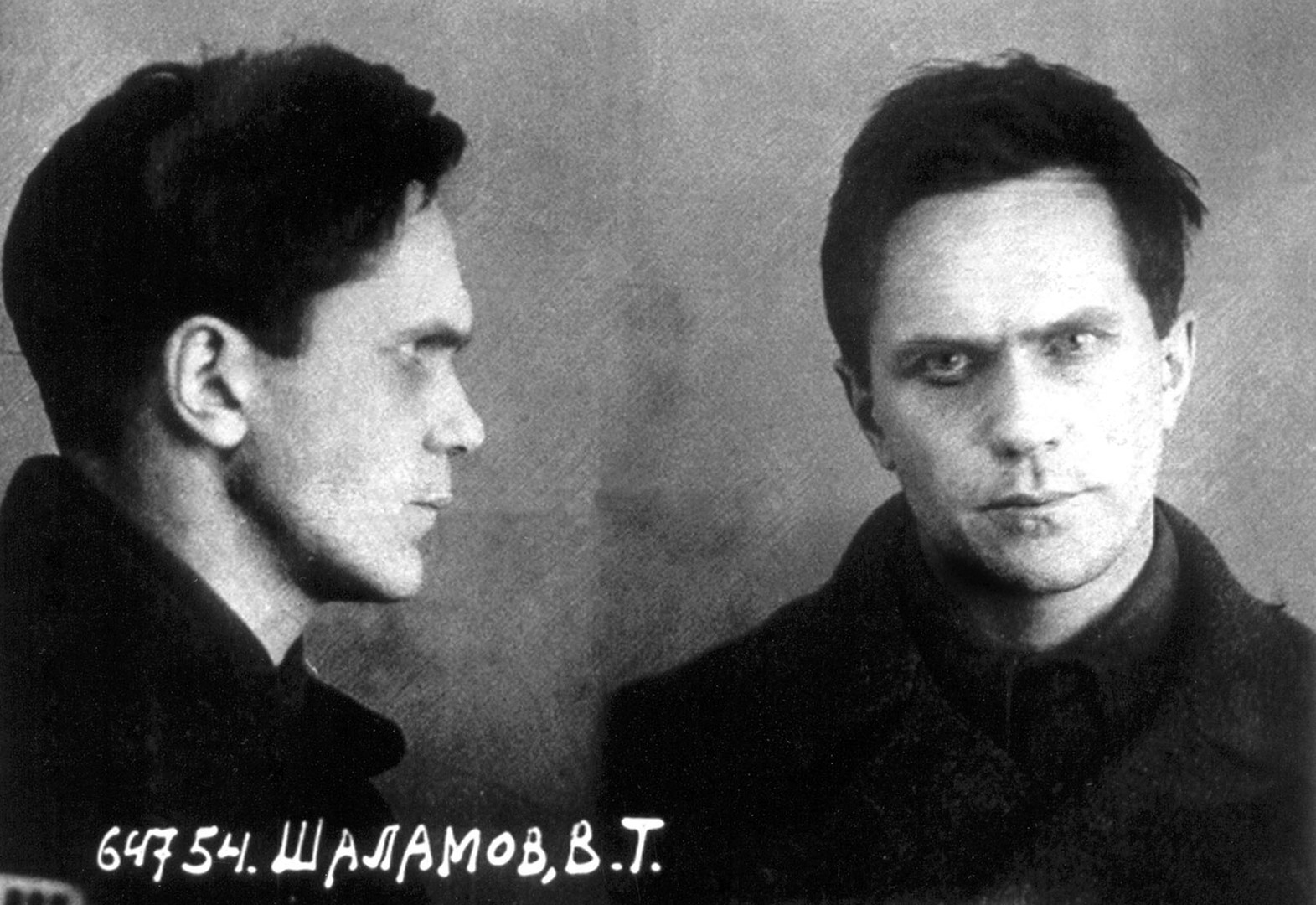

Varlam Shalamov's personal file after arrest in 1937.

NKVD archiveIn Kolyma Tales, Shalamov dryly depicts the horrifying life in the camp; people barely alive, starving and forced to do hard labor, sometimes in -30 degrees Celsius. For Shalamov, the camps became proof of people’s animalistic nature.

The notorious story of Kolyma’s camps ended with Stalin’s death in 1953. By that time the region’s resources had mostly been mined, and no longer was there a need to send thousands of convicts to the region. This coincided with a change in the Communist Party’s course, ending mass repressions.

Dalstroy was disbanded in 1957, and the notorious labor camps were closed. Time passed, and gradually life in the Magadan Region became like any other far-flung territory in Russia, although tainted by its infamous past.

When asked whether they have lots of prisons today, Magadan locals just smile and say, “as many as you have in other regions. And there are no camps here anymore.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox