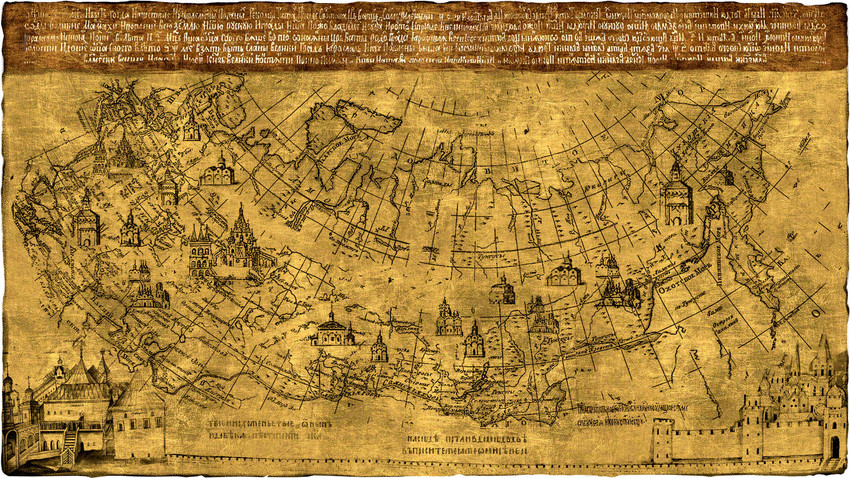

Since the Middle Ages, Russia is covered with Orthodox churches and they seem to be here to stay

Natalya NosovaWhen a priest at the most Eastern Orthodox church in Russia, situated on the Commander Islands in the Bering Sea (almost 5,000 miles east of Moscow), starts to conduct his morning liturgy at 8 AM, the previous day isn’t even over in the capital. No other religion is so widespread in Russia; almost every community, big or small, hosts its own Orthodox church.

It’s not surprising: according to statistics, approximately 75% Russian citizens consider themselves Orthodox Christians. But how did it all start?

Until the late 10th century, Slavic tribes were predominantly pagan with different communities preferring and emphasizing different “local” gods. And ordinary people were absolutely okay about that. Want to win a battle – make a sacrifice to Perun, god of thunder and war. Want a rich harvest – pray to Mokosh, the mother-of-all.

They would have never tried to change their ancient faith if it hadn’t been for the influence of the elites. Princess Olga (920 – 969) was the first ruler of Rus who was baptized in Orthodox Christianity in Byzantium in the 950s but only her grandchild Vladimir (960 – 1015) decided to baptize the whole country.

Historians mostly suppose that ambitious Vladimir didn’t care about Christ much – he wanted to unite his country under one rule and one church. First, he tried to impose the cult of Perun, his favorite pagan god, but people didn’t embrace it. The prince needed a better option and an influential foreign ally.

According to the Tale of Past Years, a Russian medieval chronicle, Vladimir, eager to examine all possible options, invited priests of different confessions: a Byzantine Orthodox, a Catholic from the Holy Roman Empire, a Muslim from Volga Bulgaria and a Khazar rabbi. Presumably, he said something like: “Okay, now tell me about your faith and impress me.”

The Muslim failed when he mentioned that Islam prohibits drinking. Shocked, Vladimir replied: “Drinking is the joy of all Rus. We cannot exist without it” and immediately sent the man away.

The rabbi also didn’t inspire the prince as he wondered: “Okay, so if Judaism is so great, where is your land?” The rabbi, confused, answered that the Holy Land of his people was occupied. “Well, – Vladimir said – if you lost your own land how can I rely on your religion?” So Russia lost its chance to convert to Judaism as well.

Vladimir rejected the German Catholic as well, stating: “Go back to where you came from, as our fathers rejected your faith and so will we”. It left him with the Byzantine priest who impressed the prince. His envoys to Constantinople were also reported to return fascinated by the beauty of Orthodox churches and divine service. So Vladimir converted to Orthodoxy himself in 988 and decided to baptize his country to this confession. At least, that’s what the

As historians mostly suppose, Vladimir’s turn to Orthodox Christianity was more about the improvement of Russians’ connections with Christian states than about sentiments: for Rus, Byzantium was an important trade partner. So sharing a religion would be useful for Vladimir.

He ordered the destruction of the statues of old gods in Kiev (back then – the capital of Rus) and had them thrown into the Volkhov River. People were crying and mourning their idols, but there was nothing they could do. As for the more remote and independent cities, Vladimir sent his warlords with armies to baptize these territories. For instance, one of them, Dobrinya, had to burn down many buildings on Novgorod to make the citizens agree to baptize.

And so it began – for almost a thousand years the powers-that-be in Russia worked with Christianity, promoting this religion and supporting priests. Only when the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917 and tried to turn Russia into an Atheist state, was religion banned and the clergy destroyed (at least, at the beginning of their rule). Then the policy became less hostile, but praying and visiting church remained frowned upon in the USSR until the late 1980s.

Since the fall of the USSR, Orthodoxy is back in the game and, according to official statistics, is quite popular. However, both priests and sociologists point out that many of those calling themselves Orthodox don’t fast or attend church regularly (79% and 63%) according to a 2014 poll. For them, religion is but a symbol, an identity.

“Faith doesn’t penetrate our life, our everyday behavior”, as Sergei Kravets, the head of Orthodox Encyclopedia center said. Probably, Prince Vladimir would be disappointed. Or perhaps not.

If you want to know more about pagan beliefs of Slavs which Vladimir suppressed so relentlessly please enjoy our piece on ancient Slavic gods.

This article is part of the Why Russia series, in which Russia Beyond answers the most popular questions about Russia

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox