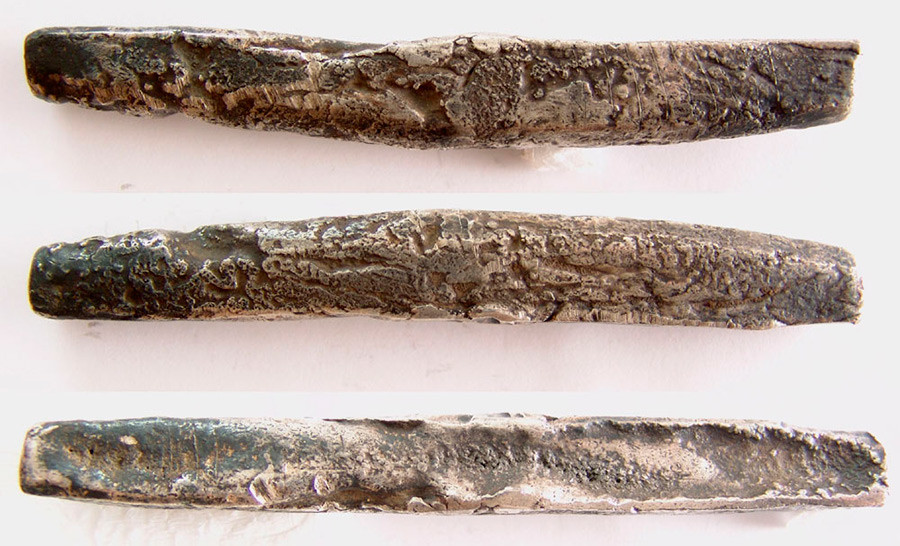

The ruble wasn’t always the most widely used means of payment in Russia. In 1316, when the ruble was first mentioned in history, its main competitor was “den’ga,” which were small coins used for daily purchases. At that time, the ruble was the name of a 200-gram silver stick used to make major payments or for storing wealth. While den’ga didn’t survive until today as a form of payment, the word is still widely used as the term for “money.”

A silver stick ruble

ATES/WikipediaIn the 14-15th centuries the silver stick ruble was used to measure coins such as den’ga, and only in the 17th century did it become a coin itself. In 1654, during the rule of Alexei Mikhailovich Romanov, the first ruble coin appeared, made from thaler coins used in Europe. Russian artisans covered the original images and replaced it with their own symbols – a horseman and a date. These rubles were called “yefimki” because the original thalers had been issued in Joachimsthal (now Czech Republic).

A "yefimok"

Public domainWith the financial reform of Peter the Great in the early 18th century the ruble was a full-fledged coin and became the foundation of the country’s monetary system.

Peter the Great's ruble coins

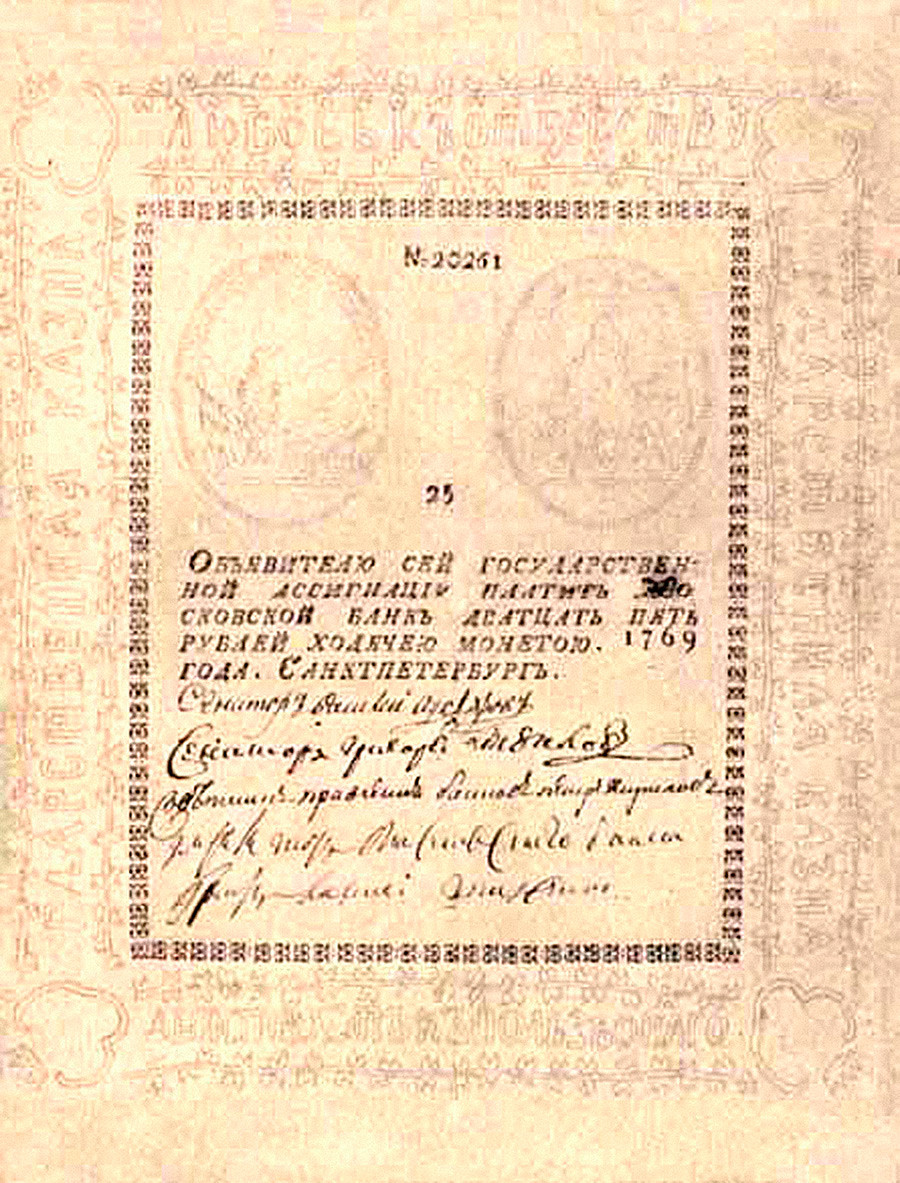

Public domainThis “coin” period of the ruble’s evolution lasted until 1769 when Catherine the Great introduced the first banknotes, which was done to cover a large budget deficit (1.8 million rubles) that was incurred from the massive expenses of the Russian-Turkish War (1768-1774).

A first ruble banknote (25 rubles)

Public domainThe most valuable banknote ever issued in the Russian Empire was called “peten’ka” because it had the image of Peter the Great. It appeared in 1898 and had a value of 500 rubles. This banknote, together with the 100-ruble “katen’ka” banknote featuring Catherine the Great, were a dream for an ordinary person. At that time it might take 2-3 months for an average working man to earn 100 rubles. A teacher’s salary, depending on his qualification, ranged from 100 to 500 rubles a year.

A so-called "peten'ka" banknote (500 rubles)

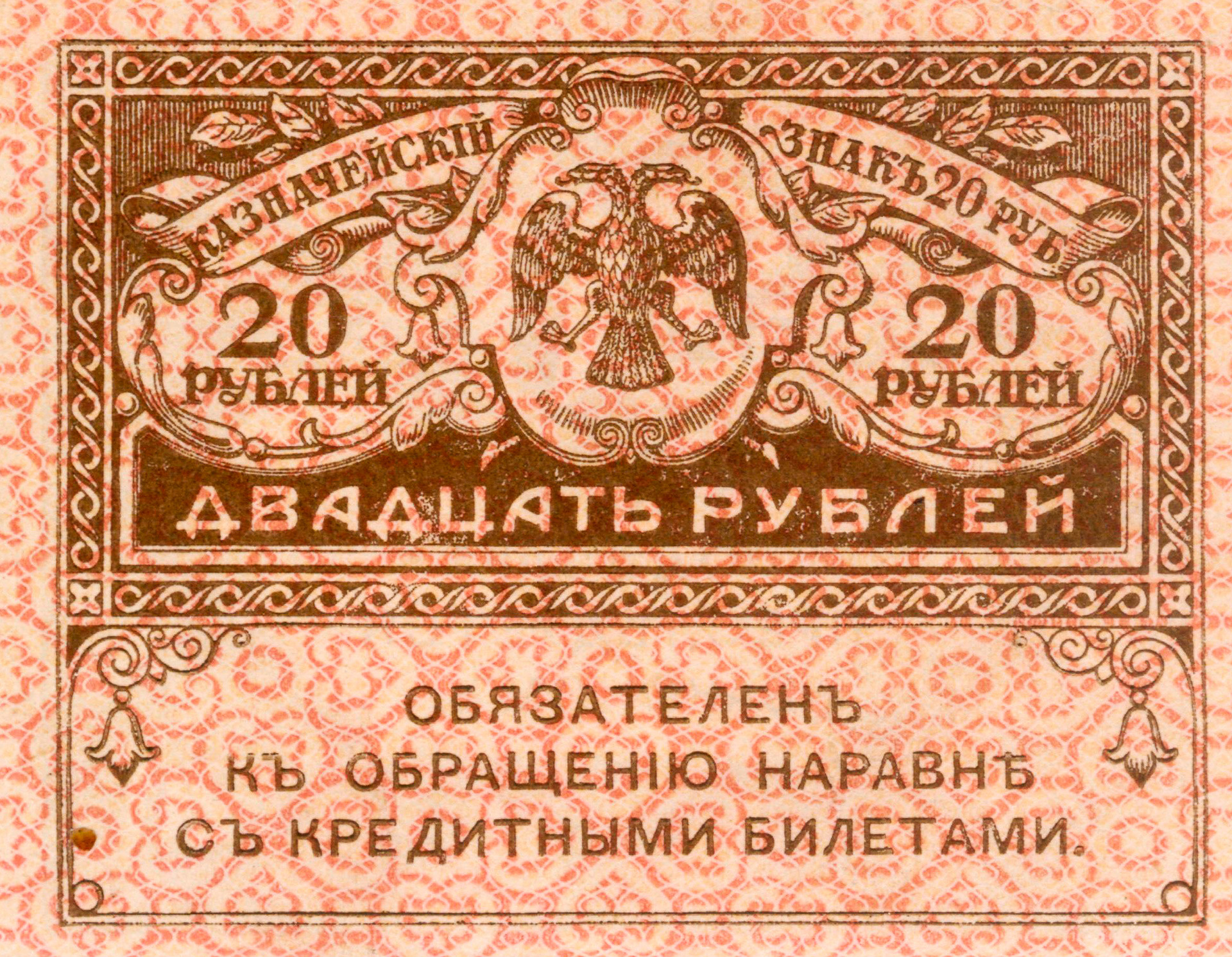

Public domainThe last imperial coin ruble was made in 1915, and resurfaced again in the form of new banknotes issued by the Provisional Government in 1917. The two-headed eagle on the new ruble banknote lost its imperial symbols (crown, power and scepter), and was portrayed on the background of a swastika – an ancient symbol of prosperity. The new banknotes disappointed the public, however, because they did not reflect the country’s power and greatness.

A 250-ruble banknote with swastika on the background

Public domainBy 1917 paper banknotes replaced coins, but even they were constantly devalued. In the early 1920s the amount of unsecured paper banknotes on the market was so high that it was more rational to burn them rather than buy wood. The Provisional Government started to issue 20- and 40-ruble banknotes that looked like stamps and were not valued by the pubic that liked to called them “kerenki” in ‘honor’ of Alexander Kerensky, the chairman of the Provisional Government. These were supplied on uncut sheets without perforation and initially were planned to be a temporary means of payment. But even after the fall of the Kerensky government in October 1917 they remained in use up until 1922.

Kerenki (20 rubles)

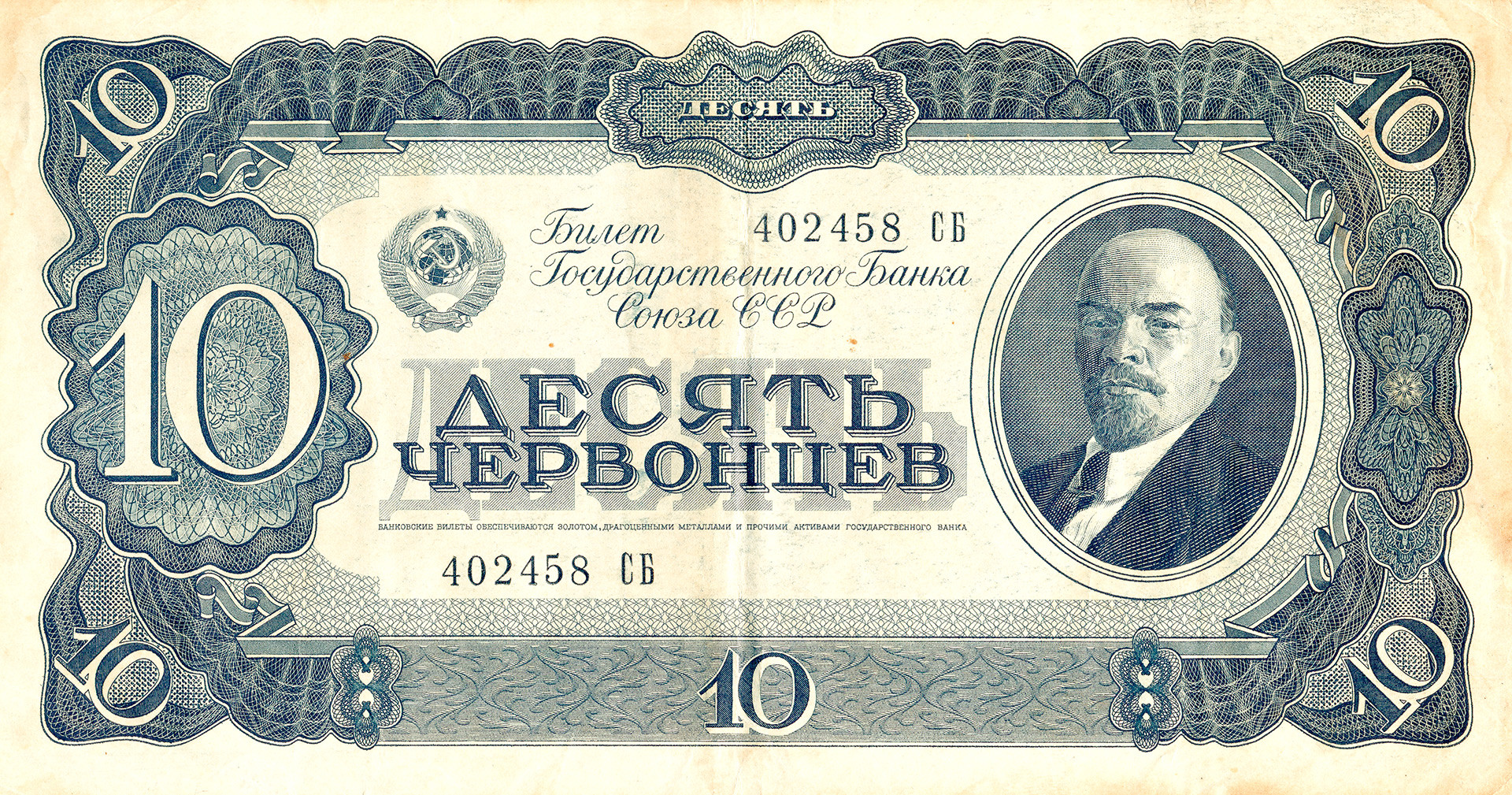

Public domainThere were many different banknotes in use at that time, including special checks to buy bread and wine. Even the old ones, like katen’ka and peten’ka were still in circulation up until 1922. In the 1930s, new banknotes appeared: so-called “simple” rubles with a low value (1, 3 and 5 rubles), and the more valuable “chervontsi” that were secured by gold reserves. The name “chervonets” was borrowed from Imperial Russia, which used the word for foreign gold coins. Lenin first appeared on a 10-ruble chervonets, and remained on the banknotes until 1991.

A 10-ruble chervonets

Public domainThe government's 1947 monetary reform banned all currencies previously in use, but they could be exchanged for new Soviet rubles. The latter’s design was quite similar to former imperial banknotes. Irina Fedorkova, the deputy director of research at the Museum of Money in Moscow, believes it was not a coincidence.

“A country that won the Great Patriotic War and saved half the world from fascism statred to feel differently: a sense of national self-awareness significantly increased and this led to the need to identify itself with a formerly great country – the Russian Empire,” said Fedorkova.

A 5-ruble banknote (1947)

Public domainIn 1961, the ruble got a new coin version, but it was not made of precious metals as before; instead, it was a copper-nickel alloy. The new period of coins and banknotes lasted until the collapse of the Soviet Union and up until now.

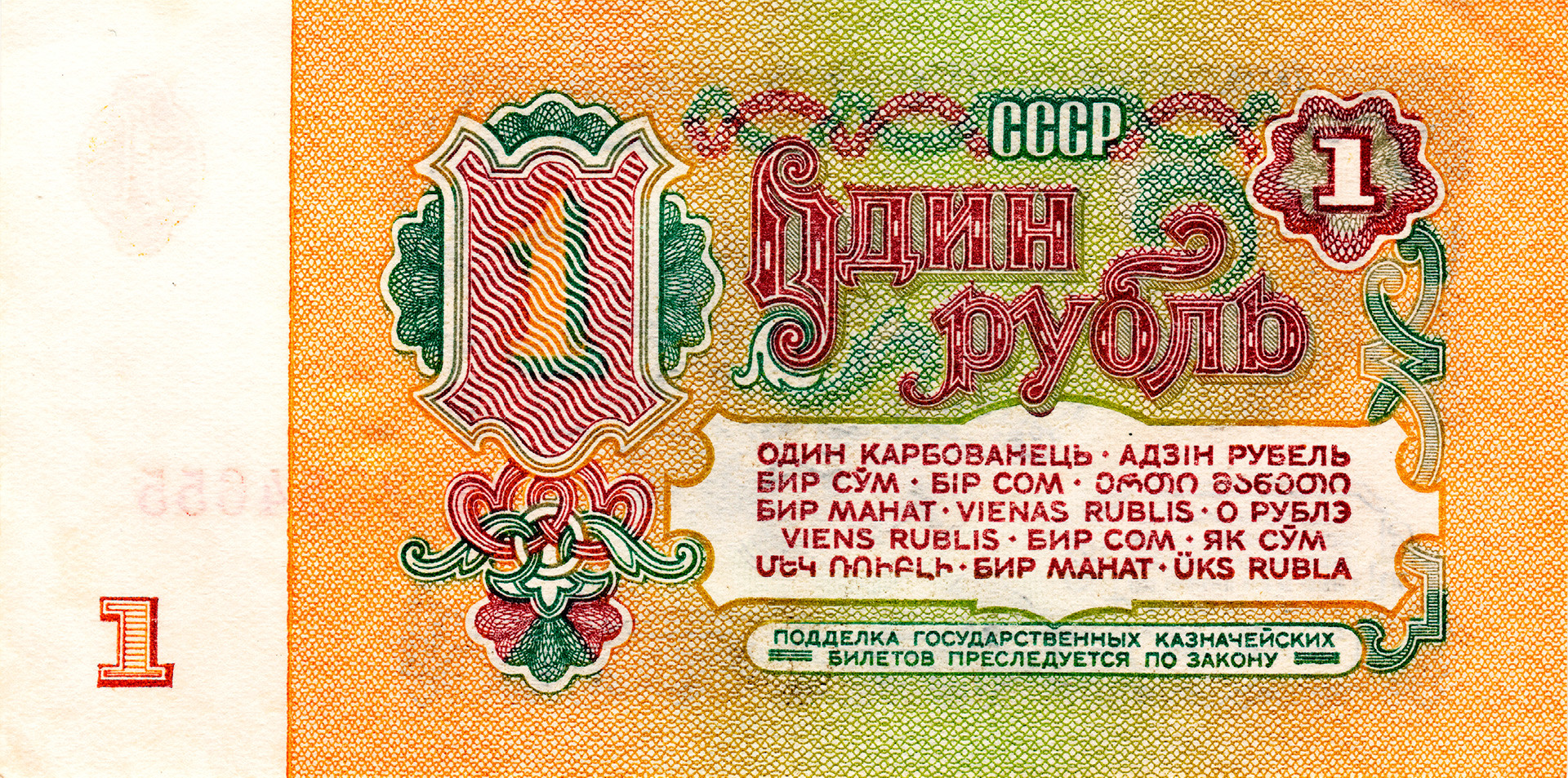

Soviet rubles could be used only inside the country, and the banknotes issued in 1961 had translations of the banknote’s value in all the official languages of the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR, new banknotes were issued that mainly had the same design but lacked translations in other languages.

A 1-ruble banknote with translation in all the official languages of the USSR

Public domainIn 1992, ruble banknotes got a slightly new image, but that didn’t last for long. The images that we see now when counting ruble cash emerged in 1995. Their value, however, was not the same as today. Back then, due to inflation, their value was different and ranged from 1,000 rubles to 50,000, 100,000 and even 500,000 rubles!

A 500,000-ruble banknote

Public domainIn 1997, the denominations were reduced to 5, 10, 50, 100 and 500 rubles, and during the 2000s slight modifications were made and there appeared banknotes of 1,000 rubles and 5,000 rubles. The latest changes to the ruble were introduced in 2017: brand new 200- and 2,000-ruble banknotes with the images of Sevastopol and the Far East.

A brand-new 2,000-ruble banknote

Public domainIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox