These days, Russians can just turn on their computers whenever they want a taste of Western culture. It wasn’t so simple in Soviet times, but even then the most cosmopolitan Russians had black-market access to the outside world and managed to pick up enough phrases to form their own slang based on English words. Beginning in the 1960s, urban youth in the USSR flaunted these phrases as a sign of status, education and connectedness.

(However, most of these terms went out of fashion right along with the Soviet Union, so don’t expect to use them in contemporary Russia without getting some strange looks.)

Suggesting a trip to Broadway in the Soviet Union didn’t necessarily mean flying to New York (not that you would have been allowed to anyway). Instead, it referred to a city’s main street—something along the lines of “main drag” in English. In St. Petersburg, “Broadway” was Nevsky Prospekt, whereas in Moscow it was Gorky Street (now called Tverskaya).

This term came into fashion in the 1960s but didn’t stick around in the Soviet vocabulary for long—it was soon replaced by number 9.

This one was pretty straightforward, although you could argue that it wasn’t really necessary to further pluralize the word “shoes.” This term was used most often when talking about “porridge shoes” (“shoozi na kashe”), a kind of massive white rubber platform shoe that was all the rage during Brezhnev’s early years as General Secretary. Ah, the good old days.

Those dubbed the polis in the Soviet Union were the regular city cops patrolling the streets (except in trench coats and ushanka hats), not the kind of police who went on secret missions to take down James Bonds and such.

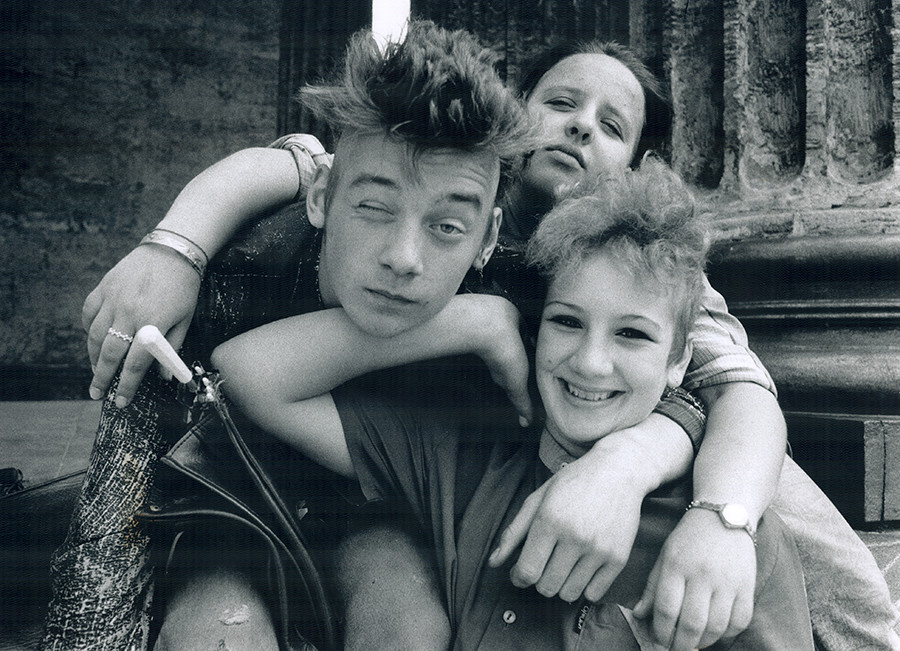

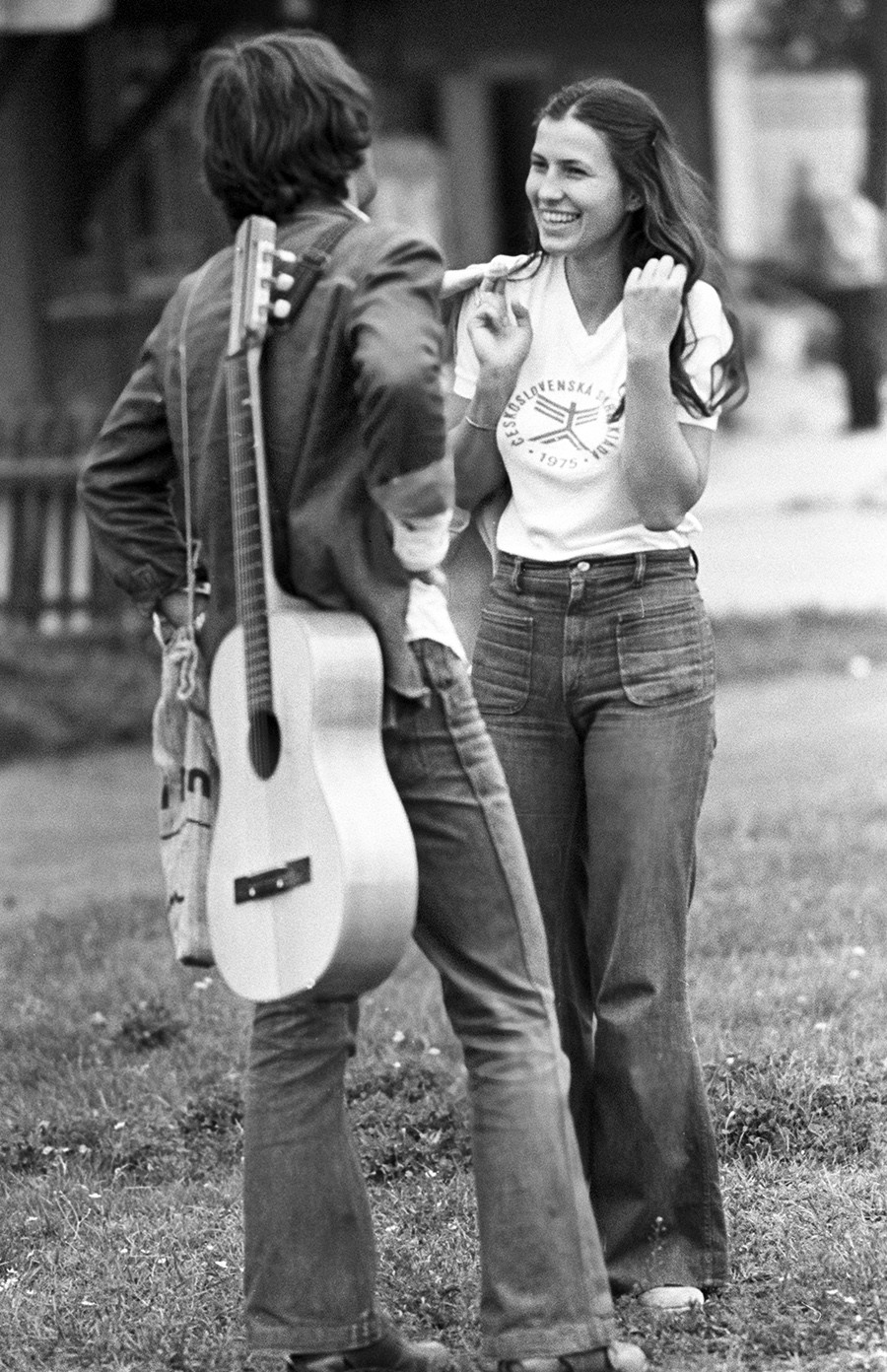

This term is little more than a classically Russian mispronunciation of the “uh” part in the word “girl.” Used by hippies and stylyagi alike during the height of the 70s, it probably best translates as something like “floosie” or “bunny.”

While this seems at first like a direct borrowing, there was actually a slight difference in meaning between “hair” and “khaer.” Not just any old 70s Soviet hairstyle got the title though–usually it had to be a long do, like a true hippie.

The phrase попилить хаер (“popilit khaer”) was also used and means “to chop off one’s hair.” And this was actually a service that the polis very enthusiastically provided to hippies for free.

In the 1980s, Soviet slang tended to move away from the kind of direct borrowing that was popular in the previous decade. This word, for example, was based on the English word “ask” and then subjected to a heavy dose of Russian verb-ization.

The practice among young, hard-up Soviet citizens of asking passersby for money was jokingly given another backstory. It supposedly began when a mythological Lithuanian called “Yanis Abaskaitis” lost his train ticket to Riga and then heroically panhandled the funds to buy a new one. Yeah, right.

Just as in English, this word was used in the music scene to denote a degree of informality in a performance. It started with Soviet hippies, who gathered for amateur, low-key, clandestine rock concerts. The word was somewhat interchangeable with the more common “kvartirnik” (a concert in an apartment, which is “kvartira” in Russian).

Like the other slang words presented here, this was not a political term used by public figures to refer to the Soviet population.

Instead, it meant “my people” or “THE people,” as in your close set of friends or the kind of group you absolutely wanted to be a part of–the cool intellectuals chilling in urban cafes with endless invitations to house parties. That sort of thing. A closer translation would be something like “the crew” or “the gang,” or perhaps “the it-crowd” or “the fast set.”

Nope, this word didn’t carry associations with urban or hip-hop culture (the USSR was still just starting to wrap its head around rock in the 1980s, so give them a chance to catch up here). It’s literally just an optional replacement for the Russian word for street (“ulitsa”) for people who wanted to go the extra mile to show how cool they were.

The adjective form, стритовый (“stritoviy”) was also in heavy usage. For example, if you advertised your party as a стритовая вечеринка (“stritovaya vecherinka,” meaning “street party”) you would have been sure to attract the coolest cats in the area.

This fine word is a heavy-handed Russification of the English verb “to drink,” both in morphology and meaning: It took the typical Russian –ать verb ending (as in аскать) and also adopted the connotations of serious drinking, i.e. drinking until you’re physically incapable of going on.

However, this term was only used in St. Petersburg. In Moscow and the rest of Russia, they tended to use бухать (‘bukhat’), which expresses the same sentiment and is still used to this day.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox