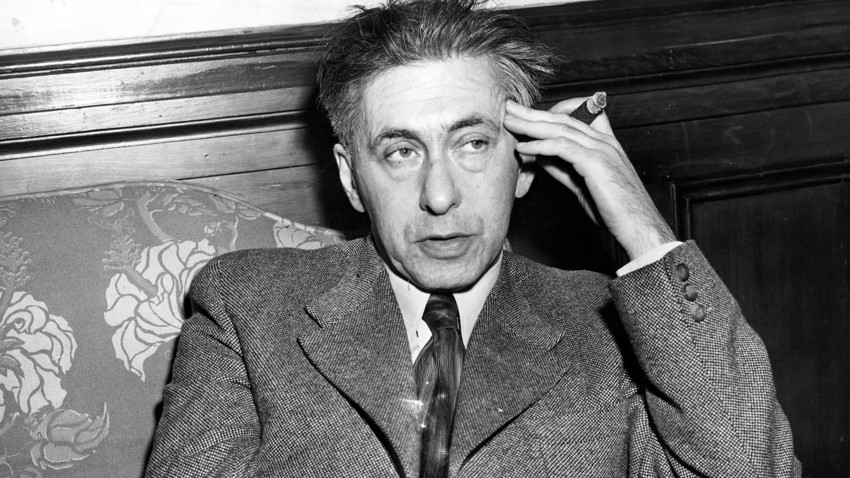

Ilya Ehrenburg (1891 - 1967) with a cigar - he was quite a smoker.

Getty ImagesWhen Vladimir Lenin met Ehrenburg in emigration (the year was 1908) he nicknamed him “Ilya the Shaggy.” Back then, Ehrenburg was a half-famished, brazen Jewish fellow who just had fled Russia after serving several months in prison for his involvement in Socialist revolutionary circles.

But that’s not the most peculiar thing about this author. Here are some things that make him unique.

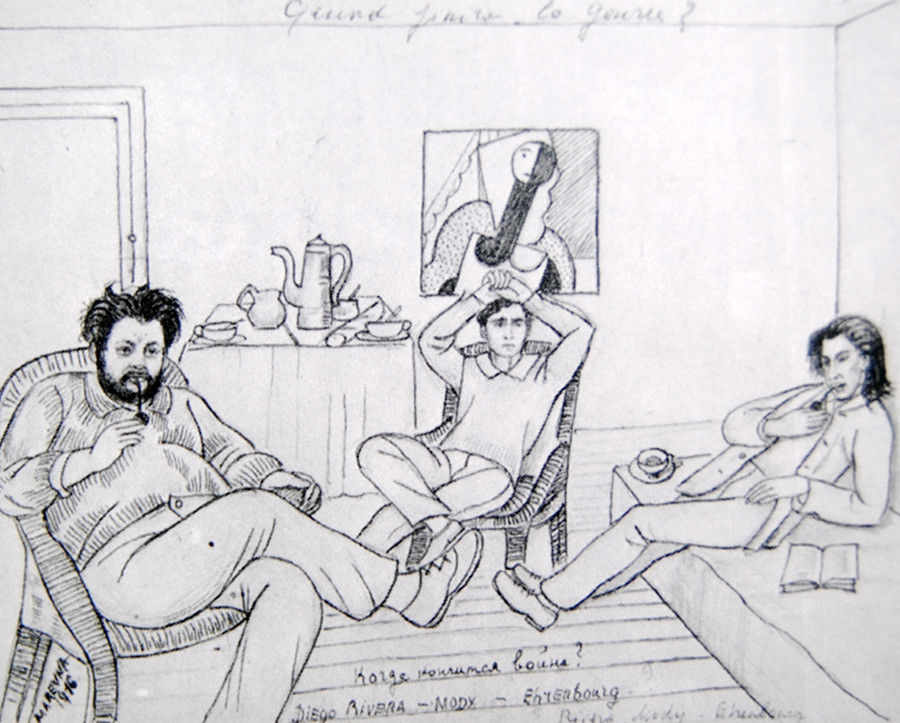

Diego Rivera, Modigliani and Ehrenburg (from left to right) in the atelier of Diego Rivera in Rue du Départ, Paris in 1916.

Public domainIlya Ehrenburg lived from 1891 to 1967; the list of his acquaintances seems endless and includes almost every celebrity of the 20th century. We already mentioned Lenin. Throughout his Paris period which lasted nine years, the author befriended Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Amedeo Modigliani, and other famous artists.

Later his circle would only widen: He met Vladimir Mayakovsky, Boris Pasternak, and Anna Akhmatova. During the Spanish

“There was no other writer in the Soviet Union who had such moral authority and connections to the Western authors of the highest rank,” Ehrenburg’s biographer Benedict Sarnov said. That’s what made Ehrenburg indispensable to the authorities – and possibly saved his life.

Young Ehrenburg (a.k.a. Ilya the Shaggy).

Public domain“There soon will be the solemn elimination of the Jewish people in Budapest, Kiev, Algiers, and many other places… The process will include burning and burying the Jews alive, spraying the fields with Jewish blood, and many more.” Sounds like Hitler’s plan during the realization of Holocaust but it’s a quotation from Ehrenburg’s first novel. Published in 1922.

The satirical book was called The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples and contained lots of gloomy and cynical predictions on the future of Europe and the world. Unfortunately, many of them came true.

Apart from the Holocaust, Ehrenburg predicted Hiroshima: In the novel, an inventor creates a weapon of mass destruction. The American who controls the weapon decides to “leave it for the Japanese.” Sounds very creepy.

Publicist Leonid Zhukhovitsky wrote: “Still stunned by those prophecies that came true. I guess young Ehrenburg had nothing of Nostradamus or Wolf Messing in him but he had a strong mind and quick reactions which let him catch the features of nations and foresee their destiny.”

At first skeptical of the revolution, Ehrenburg later joined the communist ranks and had to combine his admiration for art, freedom, the Western lifestyle (he adored Paris where he spent his youth, calling it “the school of life”), and loyalty to Moscow.

“In the 1930s, fascism was growing stronger and

“I didn’t love Stalin but I believed in him and I feared him,” Ehrenburg confessed in his memoirs. “Talking about him with my friends I used to call him “the master,” like everyone else.” In these memoirs he “admitted that there was a “conspiracy of silence” during the period of repressions,” Melikhov noted.

Ilya Ehrenburg (center) at the front during the Great Patriotic War.

Loskutov/SputnikAdolf Hitler called Ehrenburg “Stalin’s pet Jew” and promised to hang him when the Nazis reached Moscow. The German propaganda machine made Ehrenburg look like a monster, claiming that he calls for raping German women and killing German children.

In fact, Ehrenburg always emphasized that Soviet hatred should only strike Nazi invaders, not the whole nation. In his memoirs, the writer recalls: “In early 1945 I was in a German city that had been captured the previous day. I was asked to go to the German hospital and explain that no one will harm the medics or patients. The head physician wouldn’t calm down ‘Yes, but Ilya Ehrenburg, he’s so violent…’ I had to say that Ilya Ehrenburg is in Moscow to calm him down.”

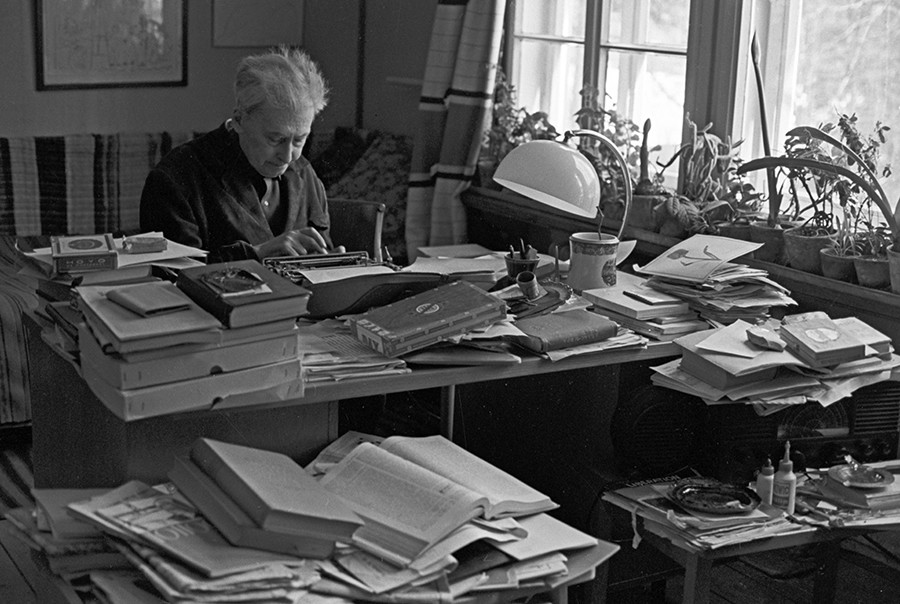

Old Ehrenburg working at his dacha in the Moscow region.

Valentin Mastyukov/Yevgeny Kassin/TASSAfter Stalin died, Ehrenburg, like many others, felt safer but did not get on with new leader Nikita Khrushchev. Yet it was him who gave a name to an era which followed Stalin’s brutal rule: The Thaw. That was the name of his novel written in 1954, which describes how life became more tolerable.

Paradoxically enough, Ehrenburg’s legacy as a publicist lives on while his books are in the shadows. After all, his reputation is rooted in the dark, highly controversial time in which he lived.

If you're interested in Russia's history, don't miss our story on how the Red Army almost captured Hitler in his bunker during WWII.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox