![Female forced laborers wearing "OST" [Ostarbeiter] badges.](https://mf.b37mrtl.ru/rbthmedia/images/2019.01/article/5c3ef31885600a267241b2e5.jpg)

Female forced laborers wearing "OST" [Ostarbeiter] badges.

Archive photoMy great-grandmother, Yevgenia Mechtaeva, was 22 years old when the Great Patriotic War started. She had just moved with her husband, a Red Army soldier, to Brest, a city on the Soviet-German demarcation line. Brest was one of the first cities to face the German onslaught on June 22, 1941.

Mechtaeva’s husband was killed as the Germans took Brest. Along with many other young women and teens, she was forcefully sent to Germany where she spent a year in a labor camp and then was ‘fortunate’ to be sent to a German family farm.

There, she was forced to work, unpaid and sometimes beaten, until the Soviets liberated her, allowing her to return home. Up until her death in 2013, she hardly mentioned her time in Germany. Her story is far from unique: according to the Nuremberg Trials about 4.9 million Soviet civilians were forcibly taken to Germany as slave labor. What was their fate?

Female forced laborers being liberated from a camp near Lodz.

Archive photoThose who came from the USSR were called Ostarbeiter – “workers from the East,” and their status in the German hierarchy of peoples was among the lowest; hence, the inhumane treatment.

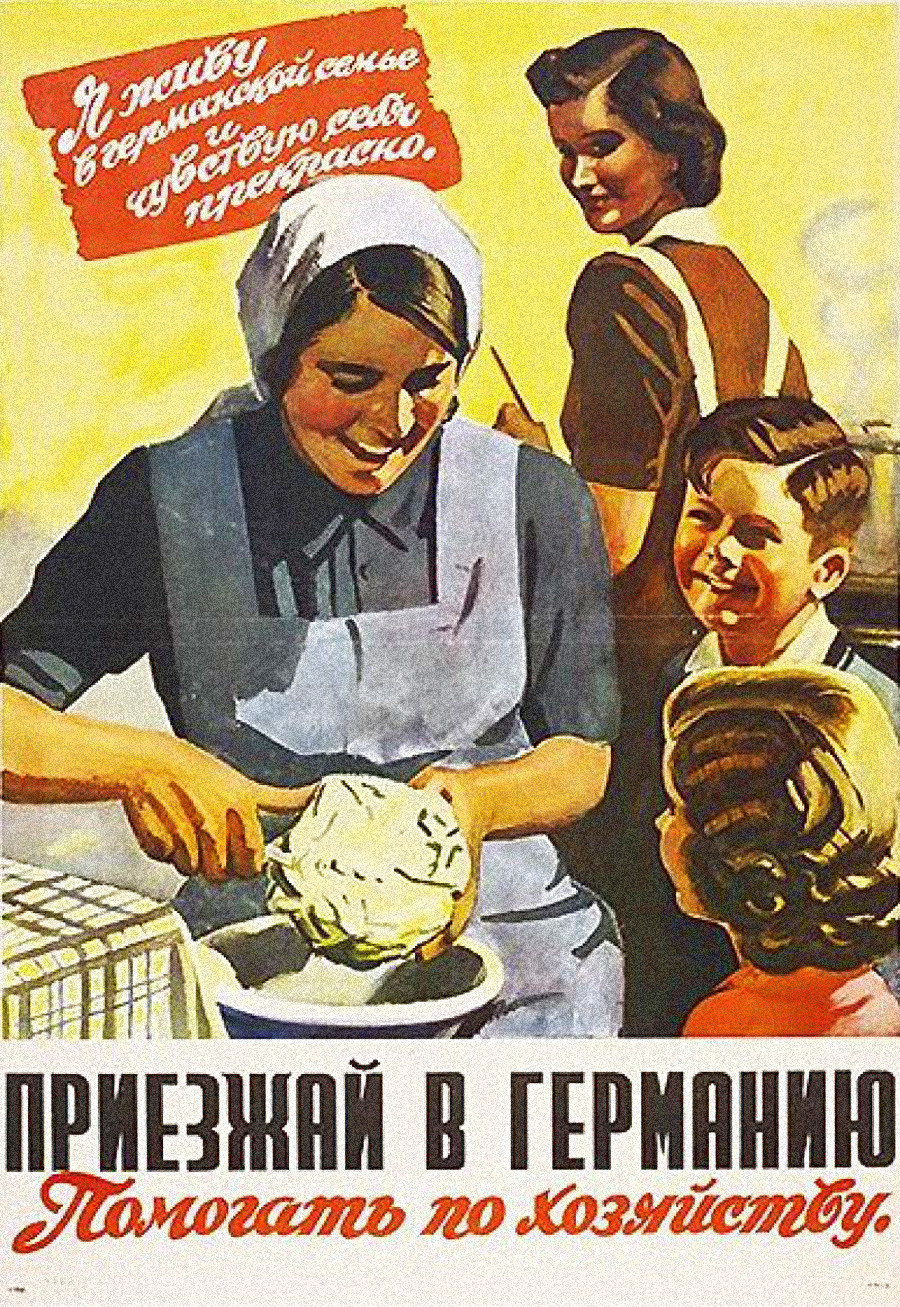

A Nazi propaganda poster which reads: "I live in a German family and feel just fine".

Archive photo

Women at the railroad station waving goodbye to a train to Germany (propaganda photo).

German Federal ArchivesThen, the Nazis resorted to using force instead of propaganda, rounding up Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians, mainly children and teens in villages and towns, and forcing them onto trains to Germany.

“They crammed us into wagons, as many as they could, so we couldn’t move our legs,” recalled Antonina Serdyukova, who was captured in Ukraine. “For a month, traveled that way.”

For the Ostarbeiter, forced to live thousands of kilometers from home, fate was like the lottery. Metallurgical plants, mines and farms needed workers, and where they ended up depended on who paid the most.

“When we arrived, there was a transfer point, I would call it a slave market,” said Fedor Panchenko from Ukraine. “In an hour, they sold the whole group of people to different hands.” Among a group of 200 people, Panchenko found himself in a factory, at the ironworks in Silesia (now Poland).

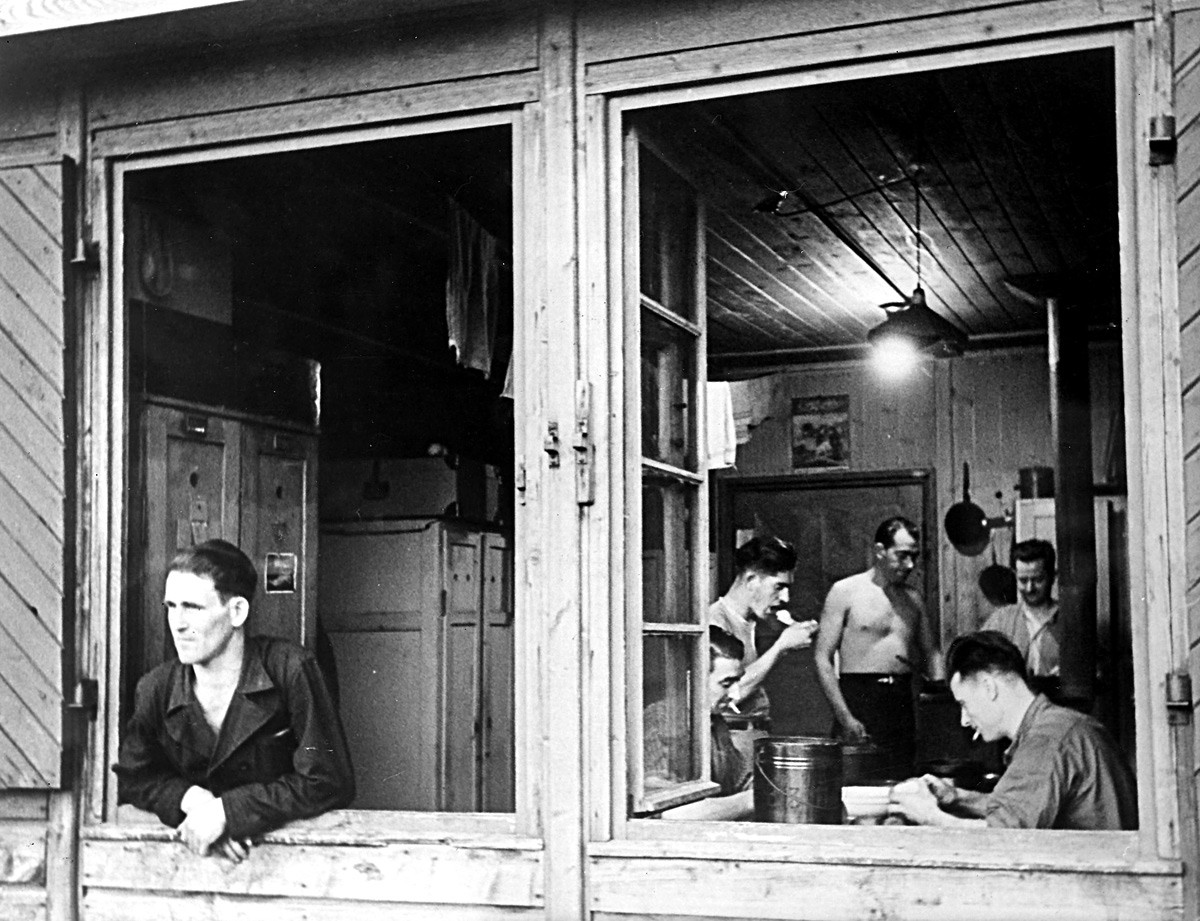

Ostarbeiter in their barracks.

Getty ImagesRutabaga is a common memory for all who lived in German captivity – the cheapest vegetable possible: unwashed, root and tops together, thrown to workers. In such conditions, typhus and malaria epidemics were common

Ostarbeiter in an armaments factory in South Germany wearing armlets as markings.

Getty ImagesMany brave youths, especially boys, attempted to escape from the labor camps – so did Fedor Panchenko. He ran away twice, roaming in Germany and hiding for a month, but then he was caught, severely beaten and sent to Auschwitz and then the concentration camp near Magdeburg, which he barely survived. Also, quite a typical fate for an Ostarbeiter – those who tried to flee usually were caught and sent to death camps.

At the same time, life in Germany wasn’t entirely horrible for all Soviet captives. “Some of us were working for landlords. And I won’t lie to you – some begged God for the war to last another four years…” recalled Panchenko. “For those living in a family, it depended on the people. Each nation has good people and villains.”

An Ostarbeiter woman working as a maid in a German house.

German Federal ArchivesSome Germans treated their Soviet servants well, even as family members, while others were cold and violent – it was a total lottery. “My masters even asked me to stay with them in Germany,” said Yevgenia Savranskaya, who worked as a maid in Świebodzin (occupied Poland). “But I said “No,” long before the Soviet army came.”

The British Army in North-West Europe liberating Russian slave workers being rescued from a cellar after it had been set on fire by a German policeman, Osnabruck, 7 April 1945.

Imperial War MuseumVictory in 1945 came hard, including for captured Soviets. After facing the possibility of death from Allied bombs falling on German cities, those who survived suffered new hardships. Sent to filtration stations run by the NKVD (Soviet counterintelligence), both war prisoners and civilians were interrogated; several thousand ended up in the GULAG, such as Lev Mishchenko, who was sentenced to ten years for working as a translator in a labor camp.

For those who came home life was also hard: German captivity was a stigma. “Fellow citizens despised us,” calmly recalls Panchenko. “I couldn’t apply for a decent job and spent 37 years working at a factory, and if there was any kind of breakage, they would say to me each time: “Oh, no surprise, you worked for Hitler.” Others kept silent about their experience in Germany for decades – they didn’t want the stigma to impact their careers or families.

Only in the late 1980s and later, after the collapse of the USSR, the fates of the Ostarbeiter received public attention – MEMORIAL, the historical and civil rights organization, along with the Germany foundation, Remembrance, Responsibility and Future, created a web project The Other Side of The War, where dozens of interviews with survivors of German captivity can be found. Their recollections in this article are taken from that site.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox