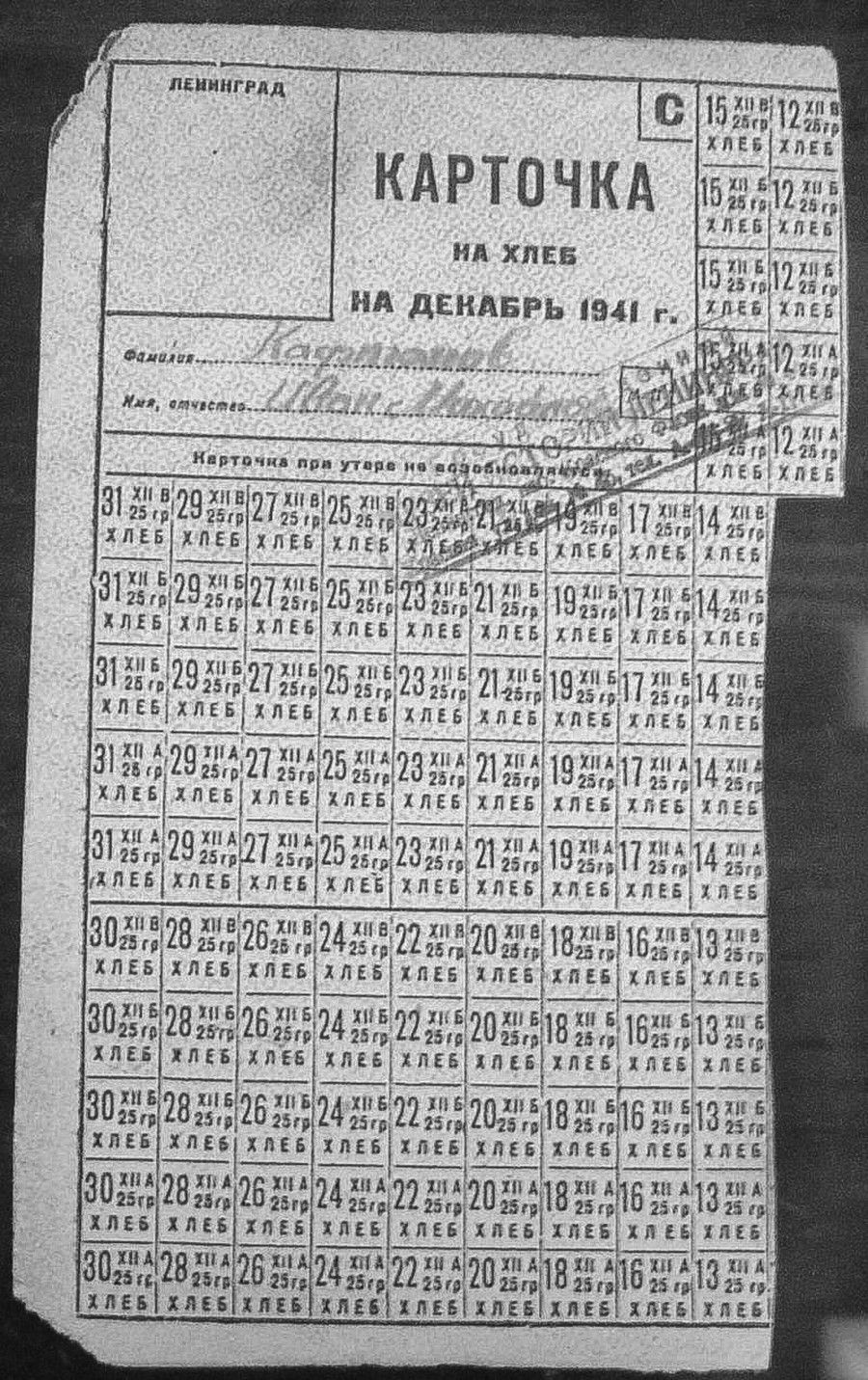

Ration stamps allowed citizens to purchase food at state-controlled prices. Each stamp indicated how much of the product could be purchased. Bread could be purchased daily, other products – once every 10 days, but there were shortages, especially with meat.

Rations slowly decreased until November-December 1941, the hardest months, when workers were allowed from 150 to 250 grams of bread daily, while civil servants, children, and dependent people were only allowed 125 grams a day. Monthly rations were as follows: workers and engineers could receive 1.5 kg of meat, 2 kg of noodles, 800 grams of fat (vegetable oil or lard), and about 1.5 kg of sugar. Civil servants could hope for 800 grams of meat, 1.5 kg noodles, 400 grams of fats, about 1.2 kg of sugar.

Ration stamps were valued enormously – losing one could lead to starvation and even death.

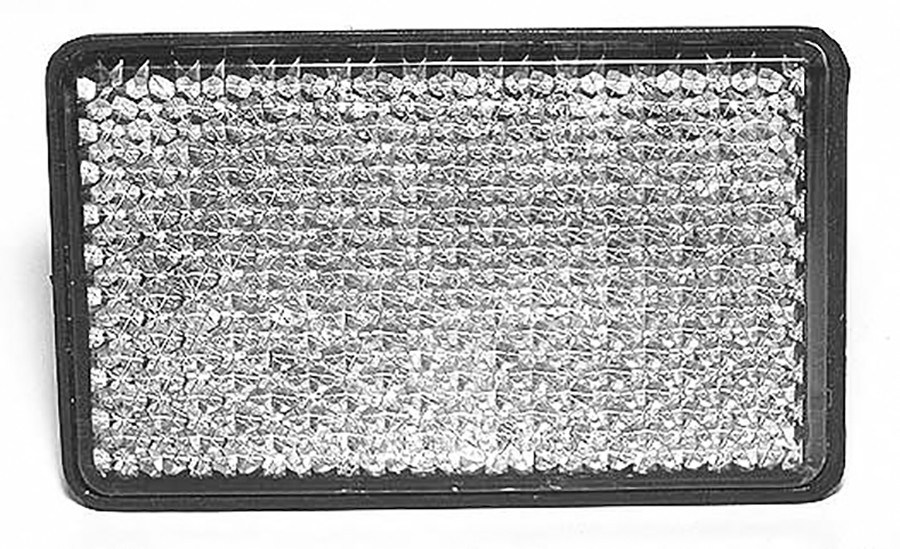

During the siege, a total blackout was compulsory in Leningrad – all lights were turned off at night so that the enemy air forces didn’t have anything to aim at from above. So people put retroreflectors, or more simply “fireflies,” as they called them during the siege, on their clothes to see each other in the dark streets.

“Fireflies” were made of scrap metal and plastic and covered with a substance made from radium-226, that glowed in the dark.

A woman dragging a sled with her malnourished husband, Leningrad, during the Siege

Israel Ozersky/SputnikThe children’s toy became the siege’s main transport and a grim symbol. A large part of the siege played out during winter. Transport in the city didn’t work because of the economic cutbacks, so people used sleds to transport personal belongings and… to move dead bodies to burial grounds.

Sofya Sagovskaya, a teacher, recalled: “As spellbound beasts in a dream, trams stand, covered in ice. Long white threads of torn cables hang down. In the morning, there are long processions of sleds with dead bodies on them, covered in white shrouds...” Many of those who survived said sleds offer an unwelcome reminder of the terrible conflict.

Such products at first were salvaged from some of the city’s factories and plants: lard and vaseline used for rubbing the slipways for the ships, bone glue and bone meal, even organic shoe polish – people found ways to cook all of this.

Glue was boiled for hours on a slow fire (the smell was unbearable), then salt, pepper –

“We kneeled near the ice hole and scooped water with a bucket… As you drag the bucket back home, the water freezes. We brought it home and thawed it. It was dirty, so we boiled it,” a siege survivor recalled. “A little for food, a little for washing. We had to collect water often. And it was very slippery, going down the shore to the ice hole was very hard. Because people were weak [from starving]: they could scoop a bucket full of water, but couldn’t get it back up. We helped each other to go up, while the water spilled.”

But at the same time, they broadcasted symphonic music and poets like Olga

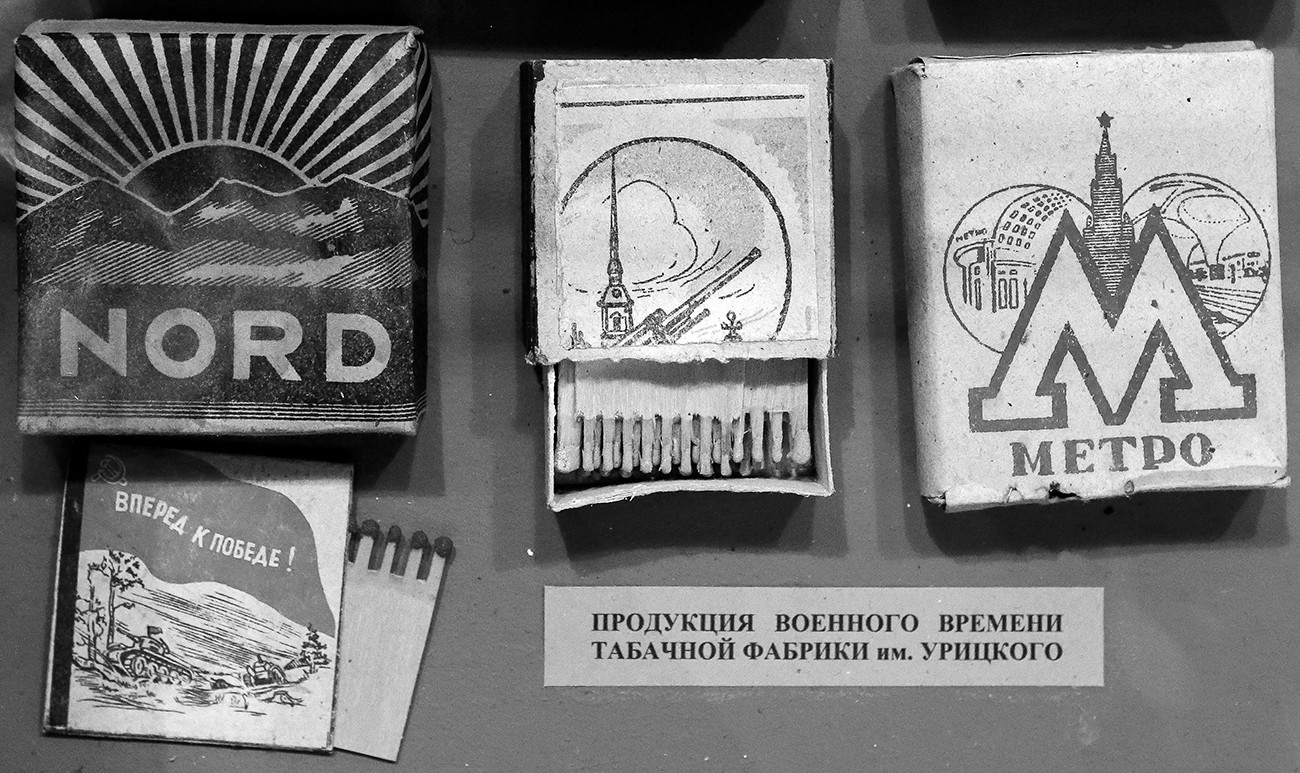

Production of Leningrad tobacco plant from 1941-1944

Alexandr Demyanchuk/SputnikWhen food shortages started, cigarettes became especially valuable – smoking kept hunger at bay and it was believed to aid people with scurvy (disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C). As there were no big tobacco reserves in the city, the local tobacco factory started adding dried leaves and hops to the tobacco. By 1942, a pack of cigarettes was as valuable as two to three daily bread rations. Amazingly, the factory didn’t stop working through the siege.

Cigarettes could buy you clothes, shoes, vegetables – during the siege, cigarettes were more valuable than money. Almost all kids learned to smoke to fight famine and frailty, and most survivors continued to smoke later in their lives through habit.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox