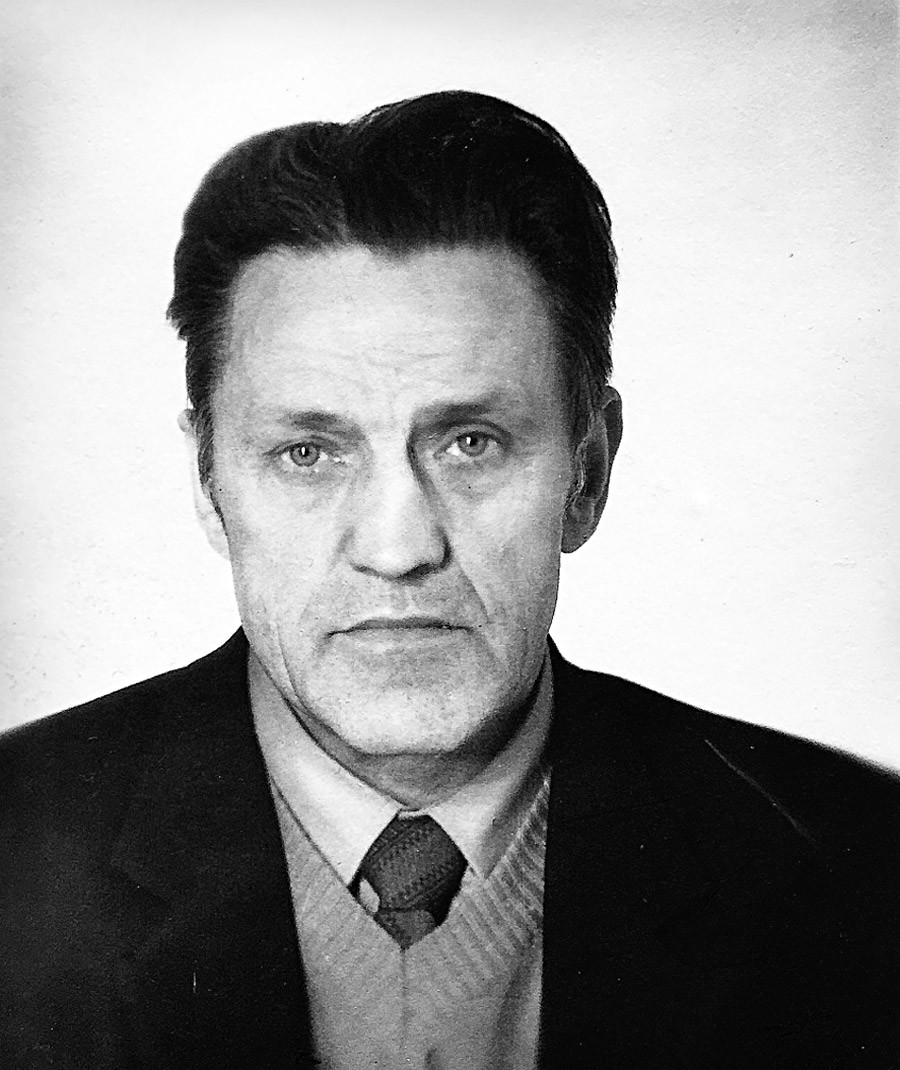

Adolf Tolkachev is shown here on vacation near the Baltic Sea in the early 1970s

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017Adolf Tolkachev remains the source of the most catastrophic military aviation leaks in all of Russian history. Working for the CIA in 1979-1985, he’d managed to pass on so much he’d even given Israel the upper hand over Palestine, whose planes were 99 percent comprised of Soviet tech. And he did it all for a monthly salary greater than that of the U.S. President.

Codename ‘Sphere’. That was the designation given to Tolkachev by his American handlers after months of repeated attempts to come into their employ finally bore fruit.

The man became known as the highest-paid Soviet traitor, raking in tens of millions of dollars by today’s standards. The more painful number was how much he’d saved the US in tech innovations - a figure the Americans debate to this day, with higher estimates reaching tens of billions - while the US Department of Defense would later admit that the US was still benefiting from Tolkachev’s leaks into the early 1990s. That’s right: American laser guidance and radar systems were propelled 10 whole years into the future thanks to one Russian traitor.

Tolkachev, an inconspicuous individual of modest stature and a melancholic face worked on radar-jamming tech and laser guidance systems for military aviation at the Fazotron research institute in Moscow. But the man had issues with his government, as well as Top Secret clearance. A very bad combination.

Adolf Tolkachev

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017In April 1979, the year he’d first approached the CIA, Tolkachev outlined his motivations in a written note. Motivations that he’d been keeping secret for five or six years up until that point. In it, he reveals how the great dissenters Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn stirred up feelings of revolt in him. And he also really liked America.

“I have not seen your country with my own eyes, and to love it unseen, I do not have enough fantasy or romanticism. However, based on some facts, I got the impression that I would prefer to live in America. It is for this very reason that I decided to offer you my collaboration”, he explained.

One thing that became increasingly clear from his notes was that Tolkachev was, above all, a family man. His crimes may appear unfathomable, but his motivations were more complex than what his most ardent accusers would have us believe. This brings us to his other key motivation: revenge. For his Jewish wife’s father, and for all the people who perished under Joseph Stalin’s Purges.

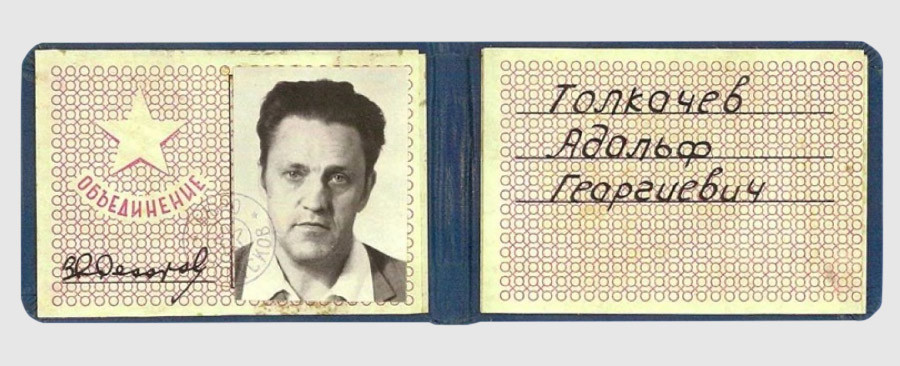

An identity card created by the CIA in an attempt to replicate Adolf Tolkachev’s building pass to facilitate removing secret documents from his Soviet military institute.

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017Born in 1935, Natalia Ivanova nee Kuzmina was a child of the Purges. Like her husband she’d worked at Fazotron, described by Tolkachev as an “antenna specialist.”

Ivanova’s mother had been executed in 1938, while her father would go on to spend many years at a labor camp, eventually freed in 1955, after Stalin’s death, only to return to Moscow and die shortly himself.

Tolkachev lived in a moderately-lavish (by late 1970s standards) two-bedroom apartment on the ninth floor, with his wife and son. The building itself - the Kudrinskaya Square High Rise - was only 400 meters from the actual US Embassy in Moscow - a fact that would later be seen as instrumental to the quiet scientist’s establishing contact and passing information to his handlers.

Before actually meeting the CIA Station Chief, Tolkachev spent weeks taking evening walks around the embassy area, picking out cars with diplomatic plates, figuring out his approach. There were many factors to consider, and zero room for error.

The Moscow gas station, where on January 12 1977, Adolf Tolkachev had first tried to make contact with the CIA

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017As Tolkachev approached the chief that night in 1977, he only asked if the person was American, then left an envelope under one of the Moscow chief’s wipers. The letter succinctly outlined that he would be interested to “discuss matters” on a “strictly confidential” basis, and with “an appropriate American official.”

It took two whole years of confidential notes before the Americans bit.

Washington was paranoid, and rightfully so. Given that the CIA still had several imminent operations in Moscow, a new diplomatic scandal with the Soviet Union was a most undesirable outcome. Not to mention the existing trend for deportations.

According to the CIA itself, it was pure chance that at a certain point in early 1978, the Pentagon had sent a memo to the CIA, requesting precisely the type of information Tolkachev claimed to possess. This changed everything.

READ MORE: How Russian double agents rose to the top of MI6 and CIA

However, in the end, it was Tolkachev’s ingenuity that broke the ice. He’d approached the then-new Moscow chief Gardner “Gus” Hathaway and his wife at their car (the way he did with all others), suggesting a surefire way of alleviating all doubt: in the note, he provided all but two of the digits of his phone number. The other two, he wrote, would be revealed on a certain day at a certain time, written on two pieces of plywood he would be holding in his hands. Hathaway decided to send his wife, who drove by the location, taking down the remaining digits.

A cable was immediately sent to Washington, and on February 26, John Guilsher, an officer proficient in Russian, was tasked to the case. A working relationship formed between the two.

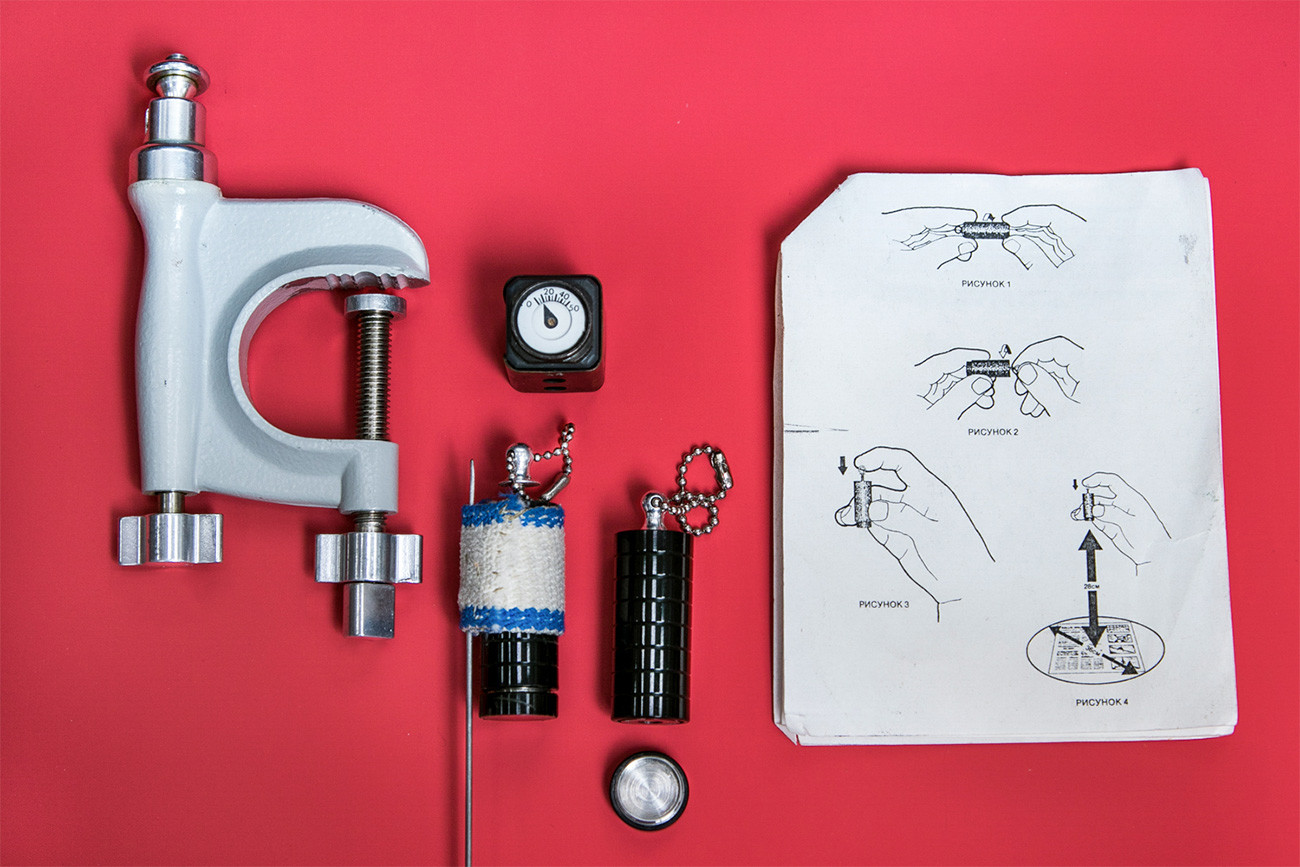

Mini cameras from CIA agent Adolf Tolkachev with manual

Ilya OgarevAmerican toys were good. Really good. By CIA’s own account, even the subsequent Pravda article on Tolkachev’s capture bore signs of KGB’s grudging praise of the myriad little decoders and cameras he was trained to use.

READ MORE: 27 Western spy tools confiscated by the Soviet KGB

In April 1980, Washington called his jam-proofing tests on Soviet fighter aircraft a “unique” piece of intelligence. This came with info on modifications to another Soviet fighter, as well as whole pages of photographed documents detailing several new models of airborne missile systems: a good day’s work, basically.

The CIA went through several cameras, refining designs, considering Tolkachev’s feedback. Often, new gear and instructions would be hidden in Moscow payphones, sometimes in a worker’s dirty glove laying on the ground.

The micro cameras were ingenious. But while Tolkachev would bring back pages of documents he’d photograph on his lunch breaks, he would also take dozens of pages of handwritten notes, containing information of the highest order.

In 1980, Tolkachev demanded a suicide pill be included in the next parcel. “The things I can hide from my family, I could never hide from the KGB,” he told Guilsher at a meeting.

One very nifty device was the SRAC (or Short-Range Agent Communications) - an emergency comms device similar to a walkie and about the size of two cigarette packs. The agreed means of signaling a readiness to meet would normally be Tolkachev opening a section of his kitchen window at a specific time. Different actions indicated different changing circumstances (sometimes a car might be parked this or that way, indicating strong surveillance in the area). When communication was difficult, SRAC was used.

Things got even riskier when Tolkachev had to use the institute’s library for documents that did not bear a direct relation to his immediate field. It was risky enough for Tolkachev to meet with CIA case officers under the KGB’s gaze, but accessing classified research without arousing suspicion was nigh impossible.

In 1983, Fazotron introduced new security regulations. This vastly complicated things. Tolkachev was the first to worry that the KGB had already by then found out: an investigation took place in his very department, focusing on leaks of information on a Soviet fighter aircraft target-recognition system.

Nothing happened. But by then, Tolkachev had already been carrying the poison pill provided by the CIA under his tongue. Things were getting tenser: meetings were skipped, regulations changed, and so on.

On one occasion, Tolkachev wrote he was so worried he’d been discovered that he burned a great deal of papers and money at his country home. On the way back to Moscow, he threw the spy equipment and remaining scraps out the window of his moving car.

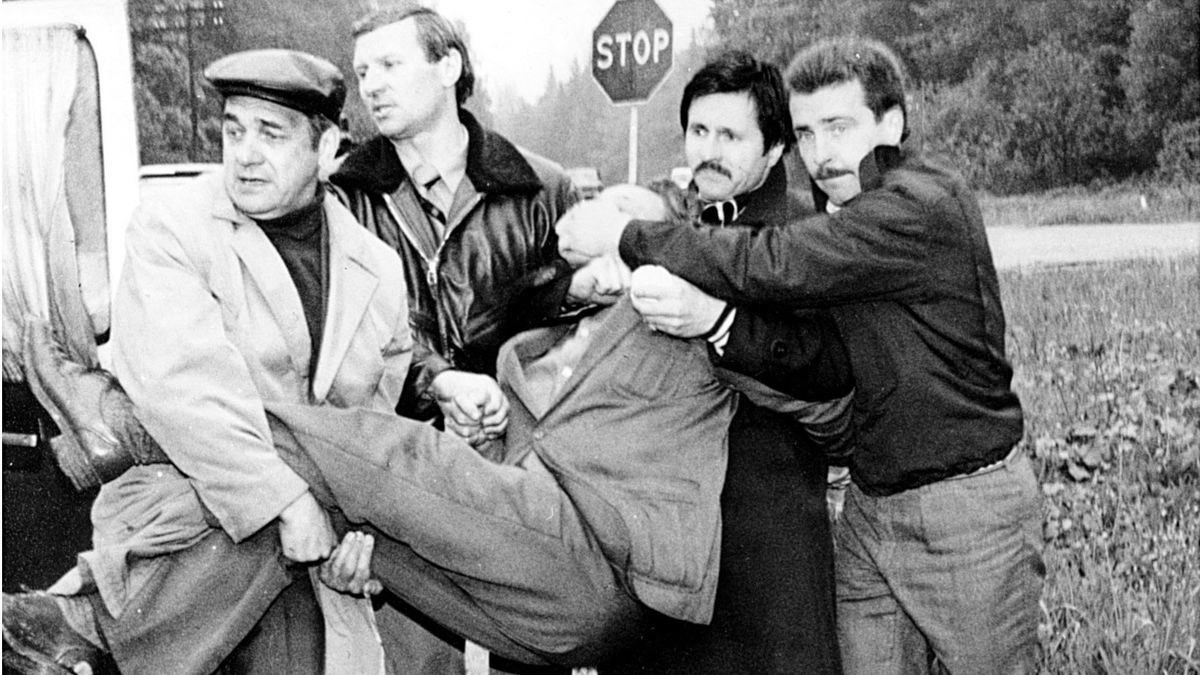

Adolf Tolkachev leaving his car at a roadblock on June 9, 1985.

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017Trouble came in June 1985. All accounts agree that, by then, the KGB had somehow found out. But even the CIA still wonders if Tolkachev had also known, and tried to warn them. Months before the fateful June meeting, he had opened the wrong transom window in the kitchen. This could have been an indication, one we’ll never be able to confirm.

On the 13th, a CIA case officer (there had been a few) was scheduled to meet with the Russian double agent. At the precise time of the meeting he was jumped by more than a dozen KGB officers, who quickly whisked him away to Lubyanka - the KGB headquarters (today FSB). But even as they methodically went through the contents of the package he’d planned to pass on to Tolkachev - miniature cameras, documents, thousands of rubles and foreign-made art supplies for his son Oleg - the CIA agent didn’t budge, and had to be set free around midnight, after notifying the American embassy. He was sent home a week later.

Adolf Tolkachev's arrest.

‘The Billion Dollar Spy’ by David E. Hoffman/Corpus, 2017The CIA officer’s arrest was highly publicized in Soviet press, but the nation would only learn of Tolkachev’s June arrest in September.

Theories differ. Some reports claim Tolkachev was burned by a disgruntled CIA officer - Edward Lee Howard, whose career did not take off after he’d been pulled off the Moscow assignment and generally deemed unfit for field duty due to his propensity for lying. He’d been fired in 1983. Being a binge drinker who did not take rejection lightly, he was the prime candidate here.

According to US press of the time, erstwhile Soviet defector Vitaliy Yurchenko provided the most believable account: that, sometime in 1984-1985, Howard had met with KGB officers in Vienna to try and score some payment for his troubles.

However, as it turns out, another CIA agent was also involved: Aldrich Ames - a CIA defector who’d started working for the KGB in 1985. He would later recount how he’d started passing information to them about leaks back in April 1985, but it wasn’t until June that he’d allegedly provided information on Tolkachev’s entire case load.

Former CIA officer Aldrich Ames

AFPThe CIA’s account, however, is not all that complete itself. Russian sources claim the Soviets had known for some time - it’s not exactly clear when, and had been feeding Tolkachev fake intelligence, in so doing subverting American efforts at replicating Soviet tech. Could it have anything to do with that 1983 security probe at Fazotron? Nobody can say.

Later in 1986, Soviet newspapers would report of Tolkachev’s execution for the crime of “high treason.”

The one good thing to come out of the whole story is Tolkachev’s son was left unscathed. Oleg Tolkachev is today a prominent Moscow architect with an office on the Pokrovka. Tolkachev’s wife, however, was hung out to dry after the whole thing blew over. When she’d contacted the Americans for the remainder of the payment for Tolkachev’s information, she received no reply.

In 2015, the CIA declassified over 900 pages detailing the operation, which were subsequently turned into a literary account in The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal by Pulitzer prize-winning author David E. Hoffman.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox