Nika Turbina

Konstantin Dudchenko/TASSIn the 1980s, Soviet newspapers published several articles about this unusual boy. At the age of three, he was performing complex calculations in his head; at five, he taught himself how to play the piano; at six, he could graph logarithmic functions; and at the age of eight, he solved a physical problem about Pluto's illumination.

The boy's name was Pavel Konoplev. He was born in Moscow. A child neuropsychologist tested Pavel when he was six and discovered that he had an IQ of 142 (for comparison, Stephen Hawking and Albert Einstein had IQs of 160). When Pavel was writing letters to Santa, he was also reading his mum’s university textbooks. His incredible intellect was all the more impressive given that when he was born he contracted an infection that doctors feared would leave him mentally handicapped.

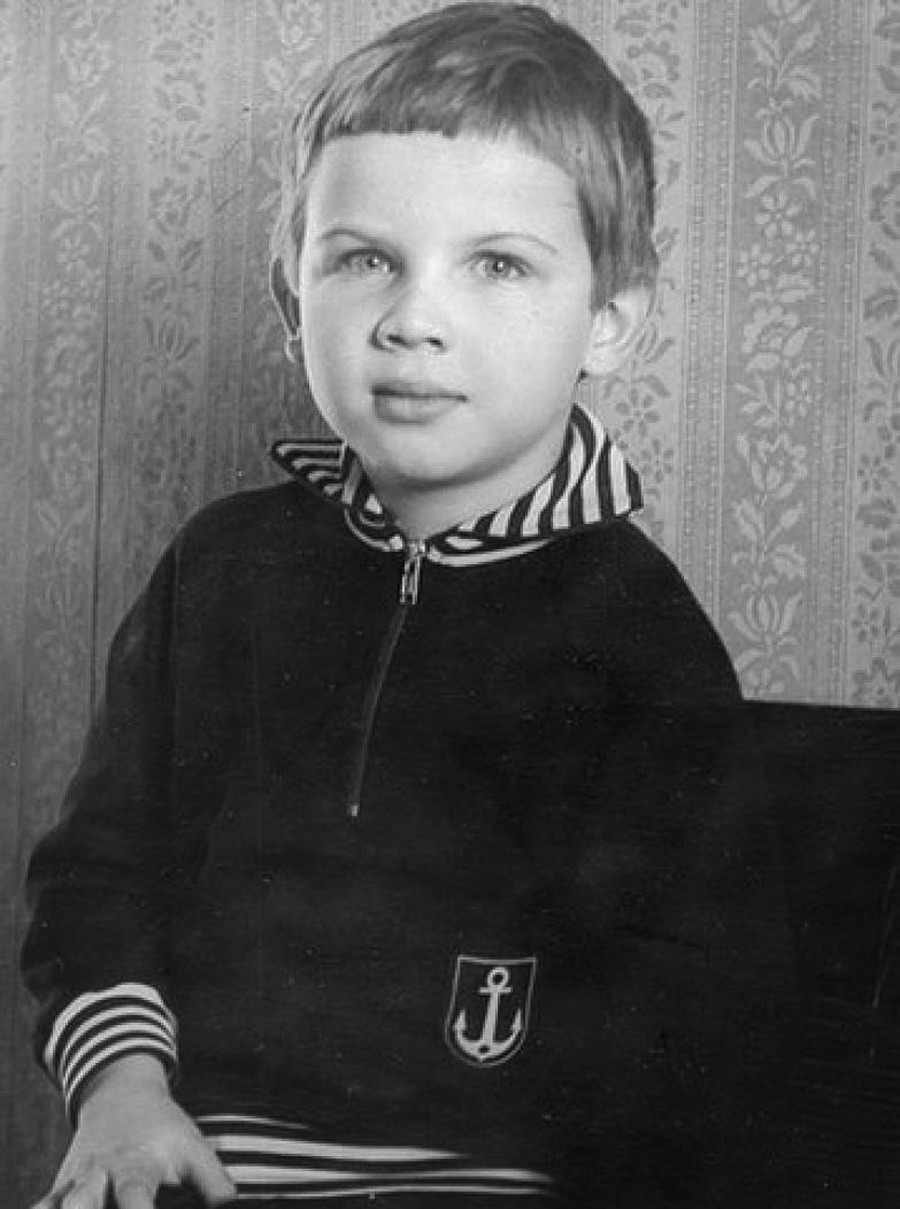

Pavel Konoplev

family archiveBefore becoming an adult Pavel was studying mathematical prediction with academics at Moscow State University. At first he was bullied but he soon made friends and earned respect – and at the tender age of 18 he became the youngest member of the district council in the country's first democratic elections.

However, Pavel started having emotional breakdowns and lashing out – he even tried to commit suidide by cutting his wrists so his parents put him in a psychiatric hospital. Doctors never worked out why his behaviour changed, but he was pumped full of drugs to calm him down in the psychiatric clinic, which caused a blood clot, killing him at the age of 29.

Nika Turbina published her first collection of poems, “Rough Copy,” in 1983 when she was nine. The book was translated into 12 languages and had a print run of 30,000 copies. At 10, she received a Golden Lion award for her work at the Venice Biennale.

Nika's poems were well beyond her years. Her writing was compared to the words of Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva. She first put pen to paper at the age of four, but she suffered from asthma and struggled to sleep as a child. Her relatives recalled how during sleepless nights, she would ask her mother or grandmother to write down the lines that she said “God has spoken” to her.

After gaining international acclaim, Nika visited the U.S. and met with Joseph Brodsky. American psychologists advised her family to take Nika to see a specialist to help her cope with the fame at such a young age.

Nika began to experience mental health issues at the age of 16. She went to Switzerland and checked herself into a psychiatric clinic in Lausanne, where she fell in love with renowned Italian psychiatrist, Giovanni Mastropaolo, 76, and became his common-law wife.

He was well-endowed “both in terms of his wallet, and in terms of what he had in his pants — he took hormones all the time,” Nika said in an interview. “He found living with me comfortable. I was 16 and he could mold me into anything he wanted.”

However, in Switzerland, Nika's breakdowns became more frequent. “I could not live in a foreign country, especially with him. He treated me like his property and was brutally jealous,” Nika recalled. A year later, she returned to Russia (in Switzerland she wrote just one poem), started to drink, was constantly depressed, and repeatedly tried to kill herself, while her poetry was getting slammed by critics. One wrote that she was “not a very talented woman.” At 27, Nika threw herself out of a window.

In 2018, a book about her life was published containing testimonies from those who knew her. It claimed, among other things, that Nika's mother forced her daughter to write poems from a young age, “squeezing them out of her, like toothpaste out of a tube.”

“I see them in advance... They appear on paper as watermarks, and I all I have to do is to ink over them” – that was how Nadya described her art. She made her drawings without sketching first and never used an eraser.

Nadya started drawing at the age of five. In 1964 when she was in the fifth grade, she had her first full-fledged exhibition as a graphic artist. A few years later, she created illustrations for Mikhail Bulgakov's novel “The Master and Margarita,” which had just been published.

Nadya Rusheva

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikDuring her life she created some 12,000 drawings: illustrations for children's fairy tales, Russian classical literature (about 50 authors), including “War and Peace” and Pushkin's fairy tales. She drew a lot and very fast: once, while listening to “The Tale of Tsar Saltan” she created 36 drawings.

Nadya's life was cut short at the age of 17 – as she bent down to tie her shoelace she had a stroke. As it later turned out, she had a congenital vascular condition that no-one knew about.

In 1982, Soviet astronomers named a small planet in her honor.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox