While tanks were rolling through Moscow's Red Square, people built barricades on bridges, Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviet Union went the way of history, Sergei Krikalev was in space. 350 km away from Earth, the Mir space station was his temporary home.

He was nicknamed "the last citizen of the USSR." When the Soviet Union broke apart into 15 separate states in 1991, Krikalev was told that he could not return home because the country that had promised to bring him back home no longer existed.

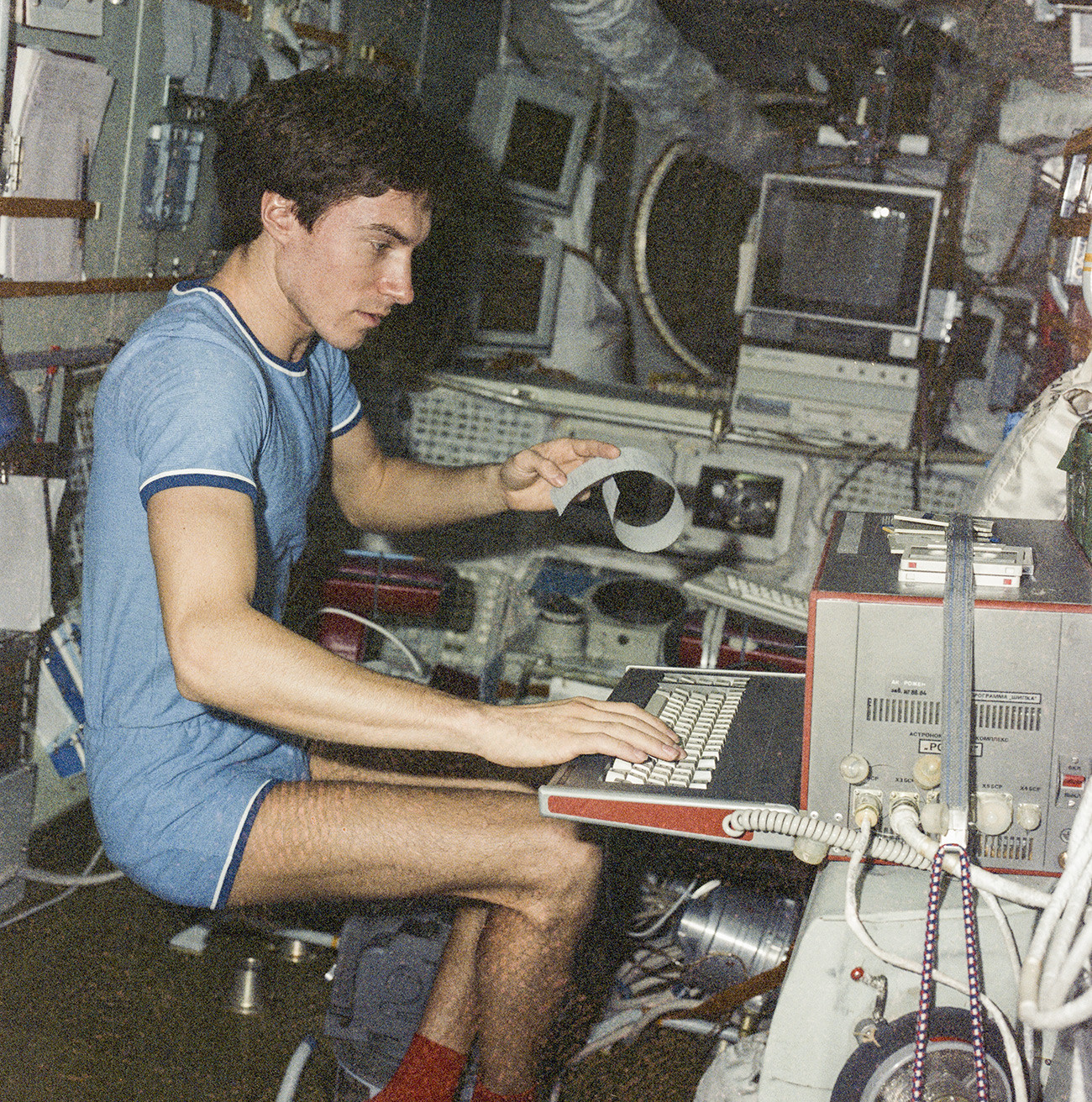

Four months earlier, Krikalev, a 33-year-old flight engineer, had set off for the Mir space station from the Soviet Baikonur Cosmodrome, which is located in Kazakhstan. Krikalev's mission was supposed to last five months, and his training had not prepared him to be in space longer than this.

Then the coup d'état happened. "For us, this came as a complete surprise,” Krikalev would recall. “We did not understand what was happening. When we were discussing it, we tried to understand how it would affect the space industry."

Sergei Krikalev

Volkov/TASSAnd affect the space industry it did. Krikalev was told there was no money to bring him back. A month later, he still got the same answer: mission control was asking him to stay out there a bit longer. Another month passed, but still the same answer yet again. "They say it’s tough for me — not really good for my health. But now the country is in such difficulty, the chance to save money must be (the) top priority,” Discover Magazine quoted him as saying.

In fact, he could have left. There was a Raduga re-entry capsule onboard the Mir, which was designed specifically for making the return to Earth. But taking it would have meant the end of Mir since there was no one else left to look after it.

"I wondered if I had the strength to survive to complete the program. I was not sure," he said. Muscle atrophy, radiation, cancer risk, the immune system becoming weaker with every passing day—these are just some of the possible consequences of a protracted space mission.

Sergei Krikalev and Valery Polykov

TASSIn Krikalev’s case, the mission lasted twice as long as originally planned. He spent 311 days, or 10 months, in space, unwittingly setting a world record in the process. Over this time, four scheduled missions were cut to two, and neither of them had space for another flight engineer.

Russia, which at that time had major money problems due to hyperinflation, was selling other countries seats to the space station on the Soyuz rocket. For example, Austria bought a seat for $7 million, while Japan purchased one for $12 million to send a TV reporter there. There was even talk of urgently selling off the Mir while it was still in working order. All of this mean that other crew members returned to Earth, while Krikalev, the only flight engineer, could not. Locked up there in space, far from home, he asked them to bring him honey in order to raise his spirits. But there was no honey, and instead they sent him lemon and horseradish.

Krikalev finally returned to Earth on March 25, 1992 after Germany paid $24 million to purchase a ticket for his replacement, Klaus-Dietrich Flade.

Upon landing, a man with the four letters “USSR” and a red Soviet flag on his spacesuit emerged from the Soyuz capsule. One report described his appearance as "pale as flour and sweaty, like a lump of wet dough." By then the whole world had heard about this “victim of space.” Four men helped him stand, supporting him as he placed his feet on the ground. One of them threw a fur coat over him, while the other brought him a bowl of broth.

While Krikalev was away, the outskirts of Arkalykh, the city where he landed, had ceased to be Soviet and had instead become part of the independent republic of Kazakhstan. The city where he lived was no longer called Leningrad—it had become St. Petersburg instead. While in space, he had orbited Earth 5,000 times and the territory of his own country had shrunk by more than 5 million square kilometers. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which had ruled the country since the 1920s, had ceased to be a political monopolist and was instead just one of many parties. His monthly salary of 600 rubles, which at the time of his departure into space was considered a good salary for a scientist, had been devalued. Now a bus driver earned twice as much.

"The change is not that radical," Krikalev would say at a press conference a few days later. "I lived on the territory of Russia, while the republics were united into the Soviet Union. Now I have returned to Russia, which is part of the Commonwealth of Independent States."

Sergey Krikalev

Global Look PressHe would be made a Hero of Russia and two years later would go on another space mission, this time becoming the first Russian cosmonaut to fly on a NASA shuttle. And a couple of years later, the first one to spend time on the new International Space Station.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox